|

There is a very politically incorrect Warner Brothers cartoon with Bugs Bunny and Yosemite Sam as a very politically incorrect ante-bellum Southern colonel. In the story line, to escape hard times up Nawth, Bugs heads South. Eventually, after what is apparently a very long journey, he leaves a desert-like North and crosses the Mason-Dixon line to find himself in a paradise of green grass, beautiful flowers and trees, blue rivers and the typical image of a gracious ante-bellum Southern plantation home. However, before the Noo Yawk rabbit can enjoy this paradise, Cunnel (Yosemite) Sam runs him back across the line shouting (and shooting) all the while. Indeed, the Cunnel is so engrossed in driving out this unwelcome Yankee, that he crosses the line and runs a few steps onto the bare, sterile Northern soil. When he recognizes what he has done he gives a cry of alarm and returns across the line declaring that he must burn his boots because they have touched “Yahnkah soil.” This cartoon—now banned as racist—is still available on the internet where much of our current social censorship is evaded by intelligent and discerning people. Yet, there is danger in this view of the South—or more precisely, the old South even when it is humorous. There are those who actually believe that had the South prevailed in the War of Secession, this mythical 19th Century way of life would have prevailed and we could once again go back to the South of “moonlight,” “magnolias” and, of course, slavery! But this is nonsense! Nothing is so sure as change. The South could no more have remained an “agrarian utopia” than the stars could have been stopped in their courses. More to the point, the South never was an agrarian utopia, still less was it fixed forever in its ways! Indeed, the ante-bellum South, as with every other part of the world, was evolving. The upper South was moving away from agriculture and towards a manufacturing economy. Industry was growing and there was even—gasp!--immigration, albeit not to the extent found elsewhere in the country. Unfortunately, the South was unable to spread its culture and way of life out into the new states and territories because of the institution of slavery. Furthermore, slavery was still essential at the time for the cash crops which financially supported the Section and paid for the North’s structure of crony capitalism known as the American System. Indeed, slavery not only added to the growing tensions and bad feelings between the Sections, but kept the South isolated from the rest of the nation. As time went on, an economic milieu consisting of slavery and tariffs, anti-black sentiment in the North and an irreconcilable difference in the vision of the future of the nation by both Sections created an atmosphere of suspicion, contempt and hatred that did not bode well for the future of the Union which Virginian George Washington wished to be loved and valued above all else by his fellow countrymen. Yet, the idea that everything of the North was rejected by the South is nonsense as books of the time by Southerners sojourning especially to New England make clear. Many Northern institutions were considered worthwhile by Southerners contrary to post-war disclaimers. Most Southern people did not reject the industry of their Northern kin, just the worst aspects of the “Yankee”—cupidity, self-righteousness and a moral double standard. Indeed, many in the South strongly believed in the need to educate poor whites through some form of public education. This concept was gaining favor among upper class Southerners because they recognized that a large population of ignorant people does not produce anything good--especially government. As well, many Southerners disliked and rejected the sort of “parochialism” that often erected roadblocks to desired progress in their own Section. For instance, while a citizen of Vermont could take a train from Montpelier straight through to Washington City because the railroad tracks were the same gauge across the intervening states, often in the South, passengers had to change trains when they came to a State line because the track gauge differed from state to state! This sort of sectional provincialism was seen by many Southerners as a barrier to natural progress and it certainly inhibited efforts by the States of the South to resist invasion when they attempted to form a “Confederate” government. We also know that slavery was falling out of favor even among those who depended upon it. And while there were those who idealized “the peculiar institution,” far more people in the South realized that things simply could not continue as they had to that point in history. However, the main problem with ending slavery was how to do so in such a way as to protect the social, political and economic way of life of the Southern people, black and white! Thomas Jefferson, no defender of slavery, put his finger on the problem when he asked the question to which Americans—North and South—had no answer: “What shall we do with the Negro?” Far from slavery being a sort of genocide, Africans throve in the South with their numbers reaching in the millions. In the Cotton States, the ratio of blacks to whites was much higher than anywhere else even in the upper South. The idea of emancipation under the circumstances of economic need and social fear made the question a great deal more important than a simple matter of morality. Even more problematic was the fear by Southern whites of a slave uprising such as had happened in Haiti and several times in the United States as well. Many was the Southern man and woman who could not—and did not wish to—forget Nat Turner’s revolt and the bloodshed surrounding it. When Northern radical abolitionists began to call for such insurrections, the relationship between the Sections was only made worse. But still, there were many—including Colonel John Mosby, a great hero of the War of Secession—who saw slavery as a succubus, draining the energy, will and spirit of the Southern people. Mosby, a Henry Clay Whig before the War, the son of a slave owner and a slave owner himself, saw the institution as crippling the people of the South. He wrote of the sons of planters losing everything in frivolous and debauched living while the sons of overseers saved their money in order to advance. All of this he blamed upon an institution to which many were addicted either economically, by habit or through fear of the consequences that would obtain if it were ended willy-nilly. But despite everything, the simple fact is that there was going to be a “New”—or more correctly a “post-slavery” South at some point in time. It could not be forestalled forever and, more to the point, neither was it desirable that it should be, a fact that was recognized by most Southerners. The major problem was how it should be brought about! And it was this conundrum that forms the foundation of the problem we have today. Do we reject a “New South” or do we reject this “New South?” In other words, would we reject a South that had evolved naturally over the years according to the will of its people and in line with their politics, culture and morality rather than being imposed by the sword? I don’t believe that we would. Is it not that which we reject a “New South” forced upon the people of the South by their conquerors? It may seem that this is “splitting hairs,” but it is not. Many objective, decent and rational people when they hear Southerners reject the “New South” envision a desire on their part to return to a time when steamboats plied the Mississippi carrying bales of cotton and young bloods in Virginia rode out to hounds. Of course, the foundation of this story-book scenario is the unspoken but understood subservient position of the black man in that South and the belief that most Southerners don’t want to return just to “moonlight and magnolias,” but to an institutionalized hierarchy based upon race. But this belief is as irrational as the belief that the South would have remained as it was had the war not happened or had she prevailed militarily in that War! There is no such thing as historical permanency. Even stars grow old and die. So what is it about this “New South” that can and should be rejected? To begin with, the religion, morality and ethics of the “Old South” were discarded and replaced by a humanist, collectivist, tyrannous understanding of the primacy of government and those who rule through it! This is the essential creed of this “New South” imposed upon it after the War by the “Old North” which had already adopted that creed. Of course, the culture that came with this particular “gift” at first seemed not so very different from the culture of the South before the War. The section was still religious—earning the name “the Bible Belt”—and patriotic—more American flags were flown in the South than in any other part of the nation—but that meant only that the slow deterioration of moral, political, ethical and social institutions was less noticeable and progressed more gradually in the South. Yet, like a boat that is slowly sinking, eventually even the uppermost parts become engulfed and the South has not escaped the filth and decay of an American culture that has lost all resemblance to Western Civilization in general and the culture of our Founders in particular. This is, sadly, the natural progression resulting from the victory of the North in the War of Secession. It may be, had this eventuality been known by more than a small number of Southern visionaries at the time, another choice would have been made in 1865 rather than that which was made. But I do not say that such a choice would have been good. I believe that had the South prevailed in the beginning—as Gen. Jackson advised when he counseled fighting under the black flag—or if a guerrilla war had been fought after the fall of Richmond, today there would be no South, old or new and her people would have met the fate of the American Indian. Fortunately, that did not occur and bad as is the present “New South,” it can at least be made to form the foundation of a “Newer South,” a South that returns to the best of its roots to rebuild that which has been destroyed in a war that has lasted one hundred and fifty years—and continues to this very day.

2 Comments

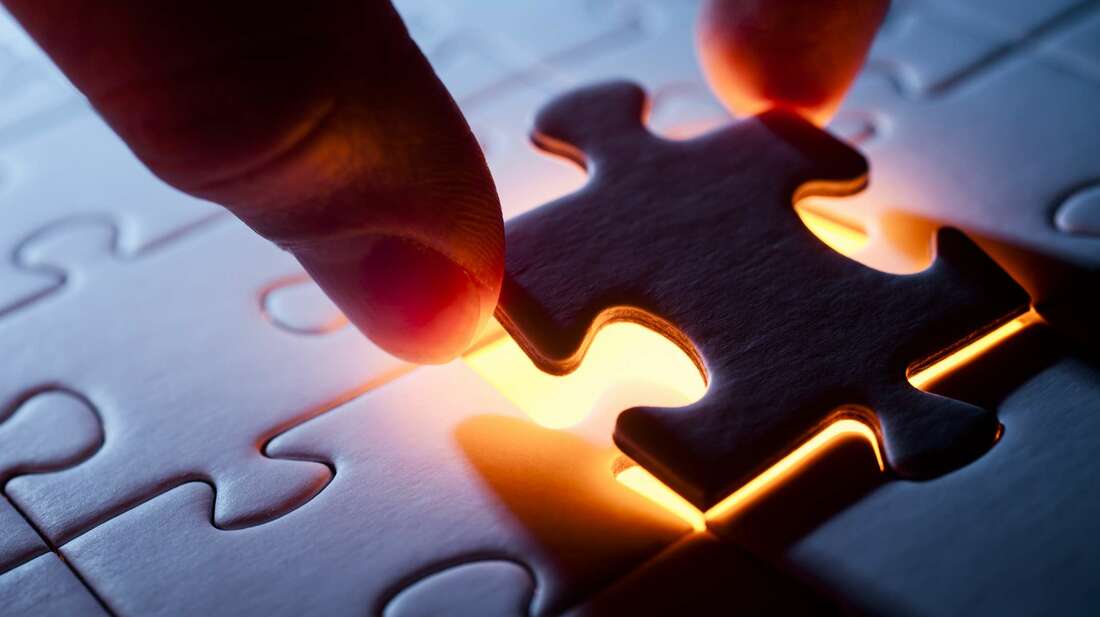

“In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. . .” Abraham Lincoln ~ First Inaugural Address I have always believed—reasonably, I think—that Lincoln used this term before ever a shot was fired in order to apportion an equal part of the blame for the war he was prepared to initiate to stop Southern secession. After all, in a civil war, both sides engage equally in a struggle to secure power over the country involved. However, we know that certainly the States of the South had no desire to wrest political power unto themselves, thus rendering the rest of the Union subject to their control. Indeed, all that the Cotton States wished to do was leave a union that had become burdensome and detrimental to the interests of their citizens. In fact, the rest of the States that seceded did so only after Lincoln called for troops to “put down the rebellion” in the Cotton States. Virginia and other States of the upper South seceded only after they realized that they were being ordered to commit treason as defined in the Constitution in order to deprive their fellow Southerners of their God given and constitutionally protected rights. Lincoln also realized that secession itself was not sufficient to bring the rest of the Union to the point at which they would countenance an invasion of the South and the war which must surely result from such an act. Secession was recognized as a constitutional right open to any state that so desired to utilize it. Even the issue of slavery—that admittedly played a major role in the matter—was not important enough for the ordinary Northerner to take up arms against those who had but lately been fellow Americans. And, of course, this is why the false flag of Fort Sumter became necessary. So, given the above, why do I now believe that Lincoln was right when he called what followed a “civil war?” In order to understand how I came to this conclusion, one must recall one of those mind tricks so popular not too many years ago. One was shown a rectangular piece of white paper and was asked to read what was written upon it. The paper contained a number of oddly shaped and placed black marks which were totally devoid of any resemblance to letters. As these shapes didn’t make up words, it seemed impossible to answer the question posited by the person playing the game. Some people never “got it” until it was explained to them! But others started to look at the paper from a different perspective and soon discovered that there were words—but the words were not the black marks! Rather, they were what originally appeared to be only the white background, the black marks serving to give shape to the white letters. The point is that until one looked at the piece of paper from an entirely different perspective, one could not answer the question. This happened to me in the matter of Lincoln’s “civil war.” I began—as the readers of the paper did—with a preconceived understanding of the situation. The South wanted to leave “the union” and Lincoln had no intention of allowing them to do so. First, the assumption was that he needed the revenues provided by the Cotton States—and he did. He is even quoted as asking what he would do for money if the Cotton States seceded since they paid over 75% of the government revenues.(*) Indeed, the entire economic foundation as a cause of the war is undeniable whether it be the tariff revenues or the threat of a new “free trade” nation existing on the same continent. But obviously, Lincoln’s method of warfare—whether it was to end slavery, an institution upon which much of Southern prosperity depended, or the waging of total war which devastated the region—was such that the South would be able to contribute little if any revenues to the federal treasury for decades after such a war’s end. As this, indeed, proved to be the case, it would seem that a simple economic motive makes no sense whatsoever! Decimating a quarter of one’s country is not a feasible strategy for economic health though the truth is that neither side believed that the war would last a year – if that long! (*From the Memoir of a Narrative Received of Colonel John B. Baldwin, of Staunton, Touching the Origin of the War, by Rev. R. L. Dabney, D. D. “I remember,” says Mr. Stuart [A. A. H. Stuart, member of the Peace Commission sent to see Lincoln in hopes of avoiding war], “that he used this homely expression: ‘If I do that, what will become of my revenue? I might as well shut up house-keeping at once!’”) So, if economics wasn’t the whole answer, then what was? Was it truly about slavery? No. When to prevent European and British recognition of the Confederacy—and as a possible military strategy to foster servile insurrection in the South—Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, the negative response from his own side effectively removed ending slavery as a rallying cry throughout the North. Furthermore, the “Union” States had severely limited the presence of blacks within their own borders, preventing them from immigrating into those States and often so circumscribing the behavior and rights of those relatively few who did reside there as to make of them slaves in all but name. Ending slavery in the South by effectively destroying its way of life could only mean that the millions of blacks in that section would have to seek their livelihood elsewhere—something that the rest of the Union was unwilling to permit. As I began to ponder what was actually being contended in the War of Secession, I realized that Lincoln stood for the Hamiltonian understanding of what the United States (with a capital “U”) was supposed to be as a nation. Unlike Jefferson’s limited Republic, Hamilton and those with him wanted if not a monarchy (Washington would not permit himself to be made a king!), then the next best thing, an Empire! Lincoln did not want to lose the South only for economic reasons but also for political reasons. Empires do not cede territory as Americans had already learned in 1776 and 1812 when the colonists and later Americans engaged the British Empire over their independence. Empires acquire territory either peacefully—as with Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase—or by the sword as in the Mexican War, a true war of empire with its own false flags. By the middle of the 19th century, America was caught up in the same heady desire for “empire building” that had engaged Europe and Britain for a century and more. A great many Americans wanted to be players on the world stage and Washington’s cautionary advice to “…avoid foreign entanglements…” had long since been forgotten. Only in the South did the rather parochial Jeffersonian ideals of moral, economic and political restraint and personal liberty still hold sway. The majority of the people of the South wanted the original Republic while the rest of the nation had moved past those modest goals and embraced an ideal of centralized power that would eventually make the United States a very large player on the world stage. The socialist revolutionists of Europe in the 1840s were finding a home not only in America but especially in the Lincoln government, both civil and military. And while there were doubtless those in the South who embraced this new view of America, the moral, ethical and especially religious character of the Southern people rejected much of what humanist socialism and atheistic communism with its all-powerful central authority proffered as path to the future. The South’s reaction to what it rightfully saw as this new course, was guided by that section’s understanding of its irreconcilable nature relative to the individual liberties of each Southern man as guaranteed in the Founding documents. The new way of centralized power was an anathema to the Southern mind. Power and wealth meant little or nothing when exchanged for conformity and the abandonment of Christianity and personal freedom. The South could not—and, more importantly, would not—adopt the path that the rest of the nation had embarked upon and the only course left open to it (even if many did not truly understand the matter in this light) was to leave and, in so doing, maintain the original founding principles—that is, a limited Republic. So, in effect, the Confederate States of America was not a new nation, but was, in fact, the original nation brought forth in 1776. Yes, there was a new nation, but that nation was the remnant which now wished to follow a very different path from that begun in 1776 and defined in 1789. This new nation retained the name of the old republic—which is what caused all the confusion in the first place—but, in fact, had over time, metamorphosed into an empire with all that that implies. Thus, when the South attempted to leave this empire that it did not support and re-establish the old republic, that faction that supported the empire waged war to maintain its borders and citizenry intact. Thus, in effect, you did have two factions waging war to gain control of a nation. The only difference here is that the people of the South were not fighting to bring the rest of the Union back to the Founders’ Republic, but rather to escape a situation they could neither prevent nor even influence. They were willing to permit their fellow “Americans” to have their empire, but they wanted to be left alone to have their republic! Of course, that could not be permitted. As previously noted, empires do not cede territory neither do they permit the existence of economic or political competition, especially in close geographical proximity. Remember, the United States had still not accepted a British presence on its northern border and after the war, weapons were sold to Irish patriots by the U. S. military for an invasion of Canada as a means of gaining the freedom of Ireland from the grip of Great Britain. The United States didn’t support that invasion, but had it been successful they would certainly have attempted to gain more territory at the expense of both the Irish and the British. So, in the end, Lincoln’s point was well made. It would be a civil war. Two factions would fight for control of a nation—or rather one faction would fight to preserve a nation—albeit within a smaller geographical setting—while the other faction would fight to overthrow that original nation, regain what it considered “lost” territory and establish an empire all of which did indeed happen as our present circumstances make so painfully clear. The confusion arises, I believe, because the new “national-no-longer-federal-government” was permitted to use without correction by either side, the claims and promises directly attributed to the nation’s founding even when those claims and promises were not just abandoned, but openly rejected. Certainly, most of the Bill of Rights—not to mention a large part of the Constitution itself—was forsaken by Lincoln’s government and military never to be reassumed. No rational claim can be made by those who approve and applaud the actions of “the Federal Union” that there was any constitutional legality involved in its actions or that the results obtained were either legal or moral. All that occurred is defended with the notion that he who prevails militarily is in the right. That is, of course, moral, ethical and philosophical—not to mention historical—nonsense. The American Civil War was far worse than most such conflicts. Whatever the changes were wrought when Cromwell supplanted Charles I, England remained England. We know this because not too many years later Charles II was restored to his father’s throne without so much as a hiccup in the life of most Englishmen. Such was not the case in the American struggle. Not only were a people and their culture purged from what remained of the political and social entity that once was the United States of America, but the nation of the Founding Fathers was laid waste, discarded and effectively destroyed. Its remnants can be seen in photographs of desolated Southern cities and the rotting corpses of those Americans who died—alas in vain—to protect and preserve it; that is, the soldiers in gray. Many books over the years have given me insights into history—insights that occasionally cause things to come together to produce a “Road to Damascus” moment. Recently the remembrance of one caused me to revisit my long-held belief that the attempt by the States of the South to establish a confederated republic upon the North American continent was doomed to failure from the beginning. Of course, this is hardly an unreasonable assumption. The strength of the North was overwhelming. Manpower, money, industry, even the production of foodstuffs from wheat to cattle made the South’s enemy too powerful to be successfully resisted for any length of time especially as the war would be waged in the South! A war lasting longer than two years must see the Confederacy fall of attrition if nothing else—that, in fact, was the case. Indeed, General Jubal Early declared that the Army of Northern Virginia had been forced to surrender because it was exhausted from defeating the foe, a not altogether preposterous assessment. Only the courage and fortitude of the Southern people allowed them to resist for as long as they did. In the same vein, I also considered the claim of those who believed that the South might have prevailed had certain actions been taken early on. General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson—among others—believed that the failure of Confederate forces to follow up the smashing victory at First Manassas (First Bull Run) and take Washington City was the most critical of the South’s lost opportunities. In like manner, Jackson opined that the invader should have been met with the black flag from the moment federal armies crossed the Potomac and entered onto Virginia’s soil. Jackson, a true Christian gentleman, was not shy in expressing his belief, stating: “I myself see in this war, if the North triumph, a dissolution of the bonds of all society. It is not alone the destruction of our property…, but … the prelude to anarchy, infidelity, and the ultimate loss of free responsible government on this continent. With these convictions, I always thought we ought to meet the Federal invaders … and raise at once the black flag … 'No quarter to the Violators of our homes and firesides!' It would … have proved true humanity and mercy. The Bible is full of such wars, and it is the only policy that would bring the North to its senses." Had the black flag been raised, it is probable that the federal government would not have been able to sustain a lengthy war at that time. Massive casualties involving ordinary Northern citizens rather than the dregs of European jails would soon have led to a demand by the people of the Union to bring the war to an end before more of their fathers, brothers, sons and husbands were dispatched on Southern soil. Indeed, it is possible that had these stratagems been utilized, the war might well have ended in 1862 with the establishment of the Confederate States of America as a nation rather than Lincoln’s contention that it was a cover for treason and insurrection. Yet something about even this idea bothered me. Yes, there would not have been defeat by attrition. And, yes, there might even have been victory—for a time! But would that victory and the country born of it been permanent—or even of any duration? Remembering the cultures of the South and its Northern foe made me recall something in another story about another war— the War of the Ring in the book, The Lord of the Rings by British author, J. R. R. Tolkien. What brought the South of 1860 to my mind in that book, was a conversation between the worldlywise wandering wizard Gandalf the Gray and the stay-at-home, naïve hobbit, Frodo Baggins. Frodo had received a found token—a mighty Ring of Power. What brought the North to mind for me was the fact that the existence of this Ring, long thought lost, had become known to its evil creator who had sent forth his wicked minions to retrieve the Ring and kill its present Bearer. In other words, two diametric forces were abroad in the same land. Knowing the strength of the Ring’s creator, Gandalf warns Frodo that “Middle Earth,” the world outside of the hobbit’s prosaic, parochial homeland of the “Shire,” was daily falling into darkness as the necromancer sought his possession using all of his strength. But the hobbit—himself prosaic and parochial and knowing little of matters outside of his own door including the danger of the talisman he holds—naively declares that all he wants is just to be left alone to live his life in peace. Sound familiar? At this point, Gandalf gives Frodo a warning, a warning from which ante-bellum Southerners too would have profited had they received it; that is, while a people—hobbits and Southerners—can wall themselves in, they cannot wall the world out! And this, of course, is the crux of the matter. The South could—and would—attempt to live as if there were peace for many years while events turned against them. However, ignoring their danger did not prevent war. From the beginning of the new nation, there had been considerable differences, cultural, social, religious and political, between the sections. After the Revolutionary War, as the effort to create a working union among the thirteen disparate “States” continued, those differences not only persisted but were exacerbated as sectional views regarding the concept of nationhood became more incompatible. Eventually, the “confederation” and then the “union” began to fracture along those lines, a rupture further intensified by the addition new territories to the body politic. With every new State, the original grievances played out over and over again, never being entirely resolved and creating more ill will and suspicion as well as more “players” in the game. In fact, it is more accurate to say that there were from the beginning, two nations and not one. Murray Rothbard in his essay, “Just War” described one of those nations thusly: “The North’s driving force, the ‘Yankees’—that ethnocultural group who either lived in New England or migrated from there to upstate New York, northern and eastern Ohio, northern Indiana, and northern Illinois—had been swept by . . . a fanatical and emotional neo-Puritanism driven by a fervent ‘postmillenialism’ which held that as a precondition of the Second Advent of Jesus Christ, man must set up a thousand-year-Kingdom of God on Earth. The Kingdom is to be a perfect society. In order to be perfect, of course, this Kingdom must be free of sin . . . . If you didn’t stamp out sin by force you yourself would not be saved. This is why “the Northern war against slavery partook of a fanatical millenialist fervor, of a cheerful willingness to uproot institutions, to commit mayhem and mass murder, to plunder and loot and destroy, all in the name of high moral principle. They were ‘humanitarians with the guillotine,’ the ‘Jacobins, the Bolsheviks of their era.’ By the middle of the 19th Century, Yankee philosophy had swept through most of the rest of the country with the exception of the South. Thus, as the majority of the States were rushing towards New England’s glorious future, they found themselves continually stymied and frustrated by a people whom they considered profligate, sinful and slothful—Southerners. The matter reached such a pass that at one point, after a Southern Senator had voted down some “progressive” Northern legislation demanding instead that the federal debt be satisfied, he found himself approached by two of his Northern colleagues. One of the gentlemen railed against the South’s continuing efforts to stymie “progress”—as they saw it—and suggested that perhaps it was time for the two sections to part company with the South seceding from the union and forming its own country! The Southern gentleman—who had more affection for the union—was aghast and asked if it would not be simpler—and less draconian—just to pay off the debt! And therein lies the insoluble problem! Unlike the rest of the nation caught up in the Spirit of the Age of Empire, the South was perfectly content to live according to the ways of Jefferson and the rest of its forefathers, following the teachings of Western Civilization with all that that entailed. Certainly Southerners embraced “progress,” but often that which their Northern brethren called “progress” deviated from what they properly believed to be right and true. They had seen such “progress” make war on Christianity and morality and preach egalitarianism and the cult of the State. To the people of the South, far more important than mere progress was Christianity, knowledge, family, honor, friendship and loyalty to one’s Section and State. Seeking a type of Middle Earth in that united States, the South represents the Shire for it was filled for the most part with (reasonably) contented inhabitants who possessed a reverence for history, a delight in food and drink, a love of home and hearth, a strong strain of faith and family, a fervent spirit of independence and a natural inclination to mind their own business and a belief that others should do the same. Southerners regarded their beloved South as a whole—and their beloved State in particular—as a garden to be cultivated and enjoyed, not a utopian citadel to be forced upon others. Parenthetically, nowhere is the difference between these sectional attitudes made more clear than in the fate of the South’s virgin forests after the War! Harriet Beecher Stowe had declared that Southern forests were not harvested for profit because Southerners were too lazy and stupid to do so. When profit-driven Northerners obtained these treasures through theft, they were decimated, never to recover. A translation of Tolkien’s Middle Earth into 19th Century America, makes it is easy to see the Southerner as the author’s beloved hobbit—and the Yankee as the hated orc. The major sticking point between the Sections was, as it always is in such circumstances, economic. From slavery to tariffs and the so-called “American system,” the matter was one of money and, of course, political power for which money is, as the old adage goes, the “mother’s milk.” In 1828 over thirty years before South Carolina signed its Articles of Secession, Missouri Senator Thomas H. Benton clearly delineated that ongoing problem on the floor of the Senate: "Before the (American) revolution [the South] was the seat of wealth ... Wealth has fled from the South, and settled in regions north of the Potomac: and this in the face of the fact, that the South, … has exported produce, since the Revolution, to the value of eight hundred millions of dollars; and the North has exported comparatively nothing. Such an export would indicate unparalleled wealth, but what is the fact? ... Under Federal legislation, the exports of the South have been the basis of the Federal revenue ...Virginia, the two Carolinas, and Georgia, may be said to defray threefourths of the annual expense of supporting the Federal Government; and of this great sum, annually furnished by them, nothing or next to nothing is returned to them, in the shape of Government expenditures. That expenditure flows…northwardly, in one uniform, uninterrupted, and perennial stream. This is the reason why wealth disappears from the South and rises up in the North. Federal legislation does all this!” The manufacturing economy of the North wanted protection for their goods through high import tariffs. The Southern States wanted reasonable tariffs to protect their exports and to keep the price they paid for manufactured goods both domestic and imported at a reasonable rate. For though Southern produce such as cotton, tobacco and sugar, were particularly valuable, the tariff situation affected their price. And unlike Northern industries, the cost of production was dependent upon matters over which the planter had no control such as weather, pests and blight. Nonetheless, Southern cotton—which was superior to that grown anywhere else—was so valuable that during the War, many a Yankee officer spent more time stealing cotton than fighting. By contrast, the industries of the North were frequently plagued with corruption or were profligate and thus failed to create the type of wealth seen in the South even with the protection of high tariffs. It thus became apparent to Northerners that they could not gain the wealth they desired except by confiscation of Southern wealth through high tariffs. And as the South was permanently isolated by strictures against the spread of slavery into new territories (strictures which Southern States themselves had helped put into place!) the balance of power in the Congress inescapably fell into the hands of the North assuring that the South would be their permanent economic colony. By 1860, this situation together with the rise of radical abolitionism had led to the complete degeneration of what little “national sentiment” remained. Indeed, by that time, the desire of Southerners to be “left alone” and to live according to their own customs was barely tolerated by the rest of the nation and then only so long as their wealth kept moving North. Few were the Southerners who did not understand that the only thing standing between them and the desire of their countrymen to destroy their way of life under the guise of “ending slavery” was the fact that they—through slavery—were paying for the nation’s economic health. Yet, by 1860 even money no longer restrained the voices raised against the South. Remove that tribute and there would no longer be any reason to restrain violence. The proof of this contention is most clearly found in the war immediately waged upon the South by the North—led by the federal government under Lincoln—when the Cotton States sought to withdraw from the Union taking their wealth with them. It was not the States and the People of the South that Lincoln and the rest of the Union wanted to retain, but the wealth of the South and if that wealth could not be obtained through peaceful union—and political theft—then it would be obtained through murderous conquest. Then there remains the question of why the South was so hated, especially by New England. Of course, the first answer is always slavery! The licentious and indolent planter aristocracy with their brutal taskmasters enslaved, debauched and exploited the innocent Negro while the rest of the Union stood by helpless to put an end to this moral monstrosity because it was protected under the Constitution. At least that is the way the matter is portrayed today. However, back in the day as they say, with a few exceptions, a very different rhetoric was in play. Oh, the “planter aristocracy” was indeed portrayed as licentious, greedy, evil and indolent without a doubt and the rest of the whites of the South who were not of that class were seen as morally deficient or just plain stupid, violent and brutal. From the highest to the lowest, the people of the South were regarded by their fellow Americans as only slightly better than the savage aborigines with whom they had been at war since the first ships landed in the New World. It was only because of their race that Southerners were tolerated at all and, in fact, even that was called into question. When Jefferson was elected president, Northern newspapers wrote of “our first black President” and not simply because Jefferson owned slaves! There were a lot of Northerners who also still owned slaves. It was the amicable relationship between the races in the South that caused New Englanders to look with disgust on men with whom they had but lately fought—and triumphed—against the forces of King George! Yet, it is obvious that New England’s disgust and contempt for the South and her people could not very well have been centered around slavery or the slave trade, which was a very “going concern” North of the Mason-Dixon line in the immediate post-Revolutionary period. In fact, early on, there were more abolitionist societies in the South than in the North until the rise of “radical abolitionism” put an end to the movement in that Section. But radicals had no love or concern for the Negro, only contempt and hatred for the white Southerner. Their plan of action was simple: foment servile insurrection and, it was hoped, encourage blacks to murder whites which would, in return, lead to the local militias killing blacks. This series of events would, of necessity, destabilize the region’s society, creating room for growing Northern influence—and profit, not to mention, of course, ridding the world of the cursed Southerner, white and black. For those who can find little excuse for the secession of the Cotton States, it must be remembered that some of the writings of these radical groups were placed into the Congressional Record by members who supported their anti-Southern sentiments and plans. Such loyalty that remained in the South was to the original union created some eighty years before in the ratification of the Constitution. Indeed, General Robert E. Lee voiced the sentiment of most of the people in the South when he stated, "All that the South has ever desired was that the Union, as established by our forefathers, should be preserved, and that government as originally organized, should be administered in truth and purity." In a way, this is very much what Frodo the Hobbit said to Gandalf the Wizard; that is, we only want to live as we have always lived! However, by 1861 it was obvious that the already embattled Constitution was doomed to irrelevance with the election of Abraham Lincoln and his sectional party. Though Lincoln had promised not to “interfere” with slavery—and he meant it!—he also intended to continue the South’s economic servitude with even higher tariffs. And he planned to press forward with a vision of the nation establishing the supremacy of the central government over the States and the People. The Republican Party had no place in the South; it was a purely sectional party which now held both the majority in Congress and the White House. Between the ever-increasing millenialist fervor of the cults of New England—as described by Mr. Rothbard—and their own political impotence, the people of the South could no longer ignore the handwriting on the wall. The above matter was succinctly summed up in a Thanksgiving sermon given by New Orleans Pastor Benjamin M. Palmer delivered one month before Louisiana seceded from the Union: "Last of all, in this great struggle, we defend the cause of God and religion. The abolition spirit is undeniably atheistic. The demon which erected its throne upon the guillotine in the days of Robespierre... which abolished the Sabbath and worshipped reason in the person of a harlot, yet survives to work other horrors . . . Among a people so generally religious as the American, a disguise must be worn; but it is the same old threadbare disguise of the advocacy of human rights . . . the decree has gone forth which strikes at God by striking at all subordination and law. The spirit of atheism, which knows no God who tolerates evil, no Bible that sanctions law, and no conscience that can be bound by oaths and covenants, has selected us for its victims... To the South the high position is assigned of defending, before all nations, the cause of all religion and of all truth. In this trust, we are resisting the power which wars against constitutions and laws and compacts, against Sabbaths and sanctuaries, against the family, the State and the Church; which blasphemously invades the prerogatives of God, and rebukes the Most High for the errors of His administration; which, if it cannot snatch the reign of empire from His grasp, will lay the universe in ruins at His feet." So, finally, why could not the Confederate States of America have survived even had the war been won early on? Simple! The people of the South wished to continue to exist as they had in the past. They rejected empire and the amassing of control within the central government necessary for the establishment of an empire. They rejected a large standing army—also necessary for the establishment of political and military control. They rejected New England’s “civil religion” that had now spread throughout the nation. Indeed, the rest of the nation had become New England together with its hatred for the South and her people. They rejected the Spirit of the Age that arose among the Yankee and pressed through every aspect of his culture—a humanist, atheist, pantheist-type pseudo-religion that rejected traditional Christianity in favor of “new religions” and cults foreign to the mind and soul of the people of the South. For though Southerners did not seek to inflict their culture—what we today would call Western Civilization —on the rest of the nation wishing only, as Jefferson Davis avowed, to be “left alone,” they soon learned that empires will not permit independence and religious fanatics will not spare the infidel. As with Tolkien’s hobbits, the people of the South found that they could not “wall out” this “brave new Yankee world.” Sadly, however, unlike the fate of the hobbits in their Shire, Southerners and their Dixie were eventually overwhelmed. In 1933, James Hilton wrote a novel about a land far removed from the shadows of war gathering once again in the world. This was a place of refuge, of peace and enlightenment, a land hidden amongst the world’s highest mountains; a habitation wherein miracles occurred and love prevailed. In the story, a stranded party is rescued by the inhabitants of this paradise after their plane crashes and thus the tale begins. As it plays out, the members of that party learn that this demi-Eden exists only because it is removed from the world, unknown to men though they have now conquered the sky. They also slowly realize that they cannot simply leave this sanctuary because to do so might compromise its safety. However, trouble arises when the story’s hero— who is strangely drawn to this place—feels that he must help his brother to escape. The brother cannot live in this world of peace and contentment being very much the Yankee and filled with the need to control all around him while seeking worldly wealth and power. For the brother, this paradise is a hell. Eventually the rest willingly choose to remain, contributing to the well being of their kindly hosts with such talents as they possess. People who have never “mattered” suddenly find that they have a purpose in life. But the hero’s brother desperately wishes to return to the darkening outside world and realizing that he will probably die if he makes the attempt alone, the hero accompanies him in his effort. However, in the course of their flight, the brother is killed but the hero survives and makes his way back to civilization. Yet no sooner does he return to “the real world,” then he bends all of his efforts to seek the sanctuary he had so reluctantly abandoned. In the film made of the novel, the final scene reveals the hero once again at the pass in the mountains leading to that place whose name has become synonymous with mankind’s desire for a world without war and suffering, a world of peace, love and hope—Shangri-la. Though certainly no Shangri-la, the South, in its own way wished to maintain a culture based upon Christian moral principles and ideals, a culture that was passing away as our present world clearly demonstrates. And nowhere was its passing more swift, more heralded and more desired than in the “United States.” Alas for the South, there was no secret valley surrounded by impassible mountains to protect its inhabitants from the Yankee behemoth. Even a victory in war would only have postponed the inevitable day when that Empire assembled sufficient forces to wage war once more. Perhaps it is best that the South was defeated after only four years. Had it won, even for a brief time, the fate of the Southern people after that second “Civil War” might well have been that of the American Indian—virtual oblivion. At least today, we still have the memory of that which was defeated but not altogether lost—at least not yet. Astronomers have discovered that the universe is expanding at an ever-faster rate. Galaxies are retreating from one another while it appears that the great nebulas or “star nurseries” that brought into existence those glittering lights that adorn the night sky are becoming fewer and fewer in number, albeit, that number is still greater than our limited minds can conceive. Yet whenever something is becoming fewer without the appearance of replacements, the natural conclusion is that eventually—however long it may take!—that thing will cease to exist! Meanwhile, stars also die. Admittedly some do so quite spectacularly and spread their remains that perhaps—but only perhaps—results in the formation of new stars, while black holes, those monstrous cannibals, consume whatever gets close enough to them—including stars. Even smaller stars such as our sun, though they have a fate far more prosaic than their giant siblings, eventually shrink into white dwarfs ultimately ceasing to exist—at least as stars. Astronomers have ruefully concluded that the end of the universe as we know it will consist of nothing more than myriad black holes. And even these monsters will eventually just disappear for apparently they are not eternal but slowly over time, lose their substance. And, so, at the end, darkness will be the fate of what used to be the glories of our cosmos. It is a sad and depressing story, but apparently, barring the interposition of Almighty God, we are headed for eternal entropy—that is, the end of all things. What is entropy? It is defined as a “measure of disorder,” but it also means “the progression from something into nothing.” Entropy is a slow disintegration from the “formed” into the “unformed.” Astronomy predicts that our cosmos’ formless remnant will be utterly dark. Even The Bible mentions this, albeit in the reverse. In Genesis, Chapter One, verse Two, it is written: “And the earth was without form and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.” Being “without form and void” is the very essence of entropy. But nature is not alone in producing entropy. Human civilizations rise and flourish and then decay, eventually ending in a formless chaos, void of all that made it a civilization in the first place. We are seeing this happening today in the West and nowhere is it moving with greater speed than in the American South, a region whose history, heritage and heroes are under relentless attack from people “void” of both reason and knowledge. These vandals are fueled by a lack of intellect and morality that prevents any “light”—especially the “light of reason and knowledge”—from reaching them. They are as a black hole in the center of what was once a great civilization and thereby represent a sure sign of cultural entropy. One of the first and most prominent societal areas that reveal cultural entropy is found in the arts. In every successive civilization as entropy set in, man’s art and literature were clear signs that the process of cultural decay was underway. Western art and music clearly demonstrate this ongoing malady, indicating how we, the people of our culture, are turning away from what was once acknowledged as beautiful and worthwhile—whether in literature, art or music—and embracing that which is ugly, profane and worthless. Often this is clearly exhibited in the semantics of the art involved—for instance, the term “rap music” is an obvious oxymoron. And, of course, this applies to other forms of art as well. Sometimes there is just enough value retained to create something not altogether worthless, but even then, the subject matter is frequently of a type that a prior generation would have discarded as a waste of time, energy and materials. Recently, we were unfortunate enough to be the victims of a very real example of this decline as it appears in the art form of sculpture. The object involved is a large bronze “monument” entitled “Rumors of War.” Here, the “artist” copied from a true masterpiece portraying one of those Southern heroes presently condemned by most of society. In doing so, he replaces the greater with the significantly lesser, though, of course, his subject is embraced by today’s culture as “worthy.” It is interesting to note that the sculptor does not attempt to make his subject heroic as that word is still understood. Rather, he clads it in the wretched trappings of the inner-city ghetto—high-topped sneakers, ripped jeans, a “hoodie” and that personal grooming catastrophe, dreadlocks! The only thing “heroic” in the work is a reasonably good rendering of the horse copied directly from the original! Even the rider’s posture is odd. His head is thrown back and he appears to be anxiously looking about as if in fear of exposure; it is, in fact, a rather flawless depiction of that most popular of inner-city pastimes, looting. Indeed, one wag has already entitled the work, The Horsethief! Taken altogether objectively, it would seem that the sculptor put whatever talent he possesses into the horse, perhaps because the horse has a natural nobility that even he was able to depict. On the other hand, attempting to ennoble a black “gang-banger” is beyond even the talents of a Michelangelo! Another abuse in this particular pairing of “monuments” is the artist’s contrast between the two subjects being memorialized. He chooses the original not based upon any artistic criteria but in order to nullify the tribute being paid to the man thus originally honored. That monument was raised to Confederate General James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart. Of course, Stuart is rejected out of hand, first and foremost because he is white and secondly because he fought for the South. The present orthodoxy insists that the South fought to maintain black slavery while the North fought to “free the slaves.” Of course, that narrative will also eventually fall because whites also fought for the Union and they cannot be seen as heroes either! Right now, however, the script cannot be abandoned without confusing the acceptable interpretation. This is especially important given the lack of wisdom and rationality among those whom the artist is attempting to reach with his “message.” The sculptor, Kehinde Wiley—also black—uses the Stuart monument as a foundation for his concept, in effect, replacing the original hero Stuart with his “champion!” But Wiley’s subject represents not a man, but an archetype of the assertion that American blacks have been robbed of their superior place by evil whites! Of course, this sort of “artistic interpretation” is both intellectually and morally bankrupt. To begin with, one cannot equate an idea or concept with a human being. A concept may be excellent, but it is the product of a human mind, it is not itself human. The artist’s “heroic image” is no more genuine than a statue of Zeus and cannot be regarded in the same way as a monument to any man whose life was such that his fellow men saw fit to glorify him for posterity. So this regressive—or entropic—“art,” replaces a true hero with a symbol representing a type of man that in better days would have been rejected by a rational society. The “ghetto horseman” embodies nothing positive or worthy of being immortalized—and this is not just a matter of race. He wears the uniform of a certain class of blacks in today’s society that are distinctly unworthy of anything but censure for their brutish and criminal behaviors. In effect, this “art” selects the worse over the better, the lesser over the greater and the degenerate over the true man. If there is a stronger example of cultural entropy, I, for one, cannot imagine it. In the end, this whole effort is admittedly designed to inaugurate the removal of the great heroes of Western Civilization, replacing them with big statues of small people having no worth or purpose other than to warn of the coming darkness. On August 24th, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln wrote to politician and editor Henry J. Raymond that Raymond might seek a conference with Jefferson Davis and to tell him that hostility would cease “upon the restoration of the Union and the national authority.” In other words, three plus years of hideous bloodshed and war crimes would simply be ended on the above mentioned conditions. But there is so much more in those ten words than might be seen by the casual observer. Of course, Jefferson Davis was hardly “a casual observer!” He understood the conditions under which his nation and his people would be spared further torture and destruction but he chose not to follow the path of abject slavery. It is interesting to note that a war many people declare solemnly was fought “to abolish slavery” among blacks was in fact fought to institute slavery among all Americans. As for the first of Lincoln’s demands; that is, the “restoration of the Union:” the simple fact is that for many years participation in that “Union” had been a kind of economic and cultural slavery for the States of the South. Despised and attacked by fellow members of the “glorious Union,” they found that their wealth was not despised but, indeed, desired and as a result, year by year found its way into the coffers of those who could not be considered anything but their implacable enemies. But this was not the foremost reason that Lincoln wanted the eleven Confederate States back under the thumb of the North. It is the second demand that makes clear why Lincoln launched his war against the States of the South in the first place; that is, they had refused to observe “the national authority.” To what “national authority” does Lincoln refer? Again, it is simple. Lincoln was going—and indeed already had—nullified the Constitution and the Union of the Founders by replacing the sovereignty of the States and the People with a now national rather than federal government. Of course, this was not just Lincoln’s desire. Many in the North and in the South of both parties no longer wished to maintain the limited federal government as created by the Constitution. Both before and during the War, Lincoln spoke endlessly of “saving” not the nation or the Union but the government! The “national authority” which he wished to “restore”—although it had not existed at least openly before the War—was an all-powerful central government with himself at its head. To this very day, those who seek what Lincoln desired infest the Constitution with “amendments” and “legal interpretations” assuring that both of his demands would be institutionalized in perpetuity and that is why we have what we have today: an all powerful “national authority.” At least the People of the South can take some comfort in knowing that their ancestors did not willingly or even grudgingly accept Lincoln’s slavery while they could still lift their swords to resist it. That they failed in that effort does not detract from the effort. Anyone addicted to picture puzzles knows how frustrating it is to assemble one almost to completion only to find out that a piece is missing. The more complicated and difficult the puzzle, the more maddening it is to come near to completion only to realize that you will never accomplish your desired end for the information required is absent. And puzzles are not the only circumstance in which missing pieces can be catastrophic. Try assembling a model or making a garment when there are parts lost. A great many human endeavors as well as man-hours are brought to naught because, when all is said and done, essential components are simply not there. But missing pieces do more damage than simply aggravating those involved. When the puzzle cannot be finished or the garment assembled, the aggrieved laborer can assuage himself with a stiff drink or some other pleasantry. But what about the "missing piece" scenario when it occurs in such disciplines as the study of history? While the former examples of the consequences involved are obvious, for the historian what most often happens is that the "puzzle" is "completed" absent the missing pieces and this may often result in a faulty conclusion. The picture puzzle's missing piece is obvious; the historian's missing piece may be overlooked or, worse, ignored. Of course, the more important the historic subject, the more essential the missing piece and no subject today seems to carry with it a greater weight in the general culture than that of slavery as it existed in the antebellum South. It is not necessary to repeat yet again the general view of black slavery in the South but that view is minus a good many pieces and hence it cannot be accepted as valid. Yes, it does contain a great deal of information, but absent the rest, the conclusion invariably reached by the historian (or anyone else) is palpably false. And while it is easy enough to talk of "missing pieces," if we are attempting to invalidate the conclusions reached without them, we must find those pieces and place them into the puzzle. This is a very lengthy process so I will only make mention of two such, concentrating on one that seems to have been not so much "lost" as "ignored!" A "lost" piece can be unintentionally overlooked because the historian does not see the connection of the piece with his particular puzzle or, in the alternative, he is unaware of it in the first place. An "ignored" piece indicates an attempt to reach a conclusion that said "piece" might invalidate and that is how "history" is manufactured! The first piece of the puzzle of black slavery in the South is the role played by the slave trade and especially the involvement in that trade of the Africans themselves. Many people have this "vision" of (especially Western) slavers sailing to Africa, fitting out expeditions into the bush and "capturing" innocent natives going about their daily business. These captives were then brought back to the coast, and loaded onto sailing ships for the hideous "Middle Passage" to Europe or the New World. But this is nonsense! Now certainly, Arabs from the Middle East might have obtained slaves that way, but the easiest, cheapest and safest way to obtain an African slave was from another African! The economic system of Africa was based upon slavery. African chieftains and kings did not till the land or even mine for the great wealth of that Continent. They used the captives of eternal tribal wars as capital, keeping some and selling the rest. The fate of a captive who was not kept or sold was death. So, the ease and relative cheapness with which slaves were procured through tribal warfare and the wealth that their sale obtained from the slave traders encouraged African potentates to use slavery as their source of wealth. The idea that black slavery was a white European or American invention is ludicrous and certainly not validated by history. Because slavery is such an emotional topic, people don't bother to understand it other than all those hideous tableaus eternally presented to the gullible and naive. Furthermore, today slavery is seen only as involving blacks, but especially in colonial America, most slaves were white. Only later did that change with the African slave trade run from New England. But, most important to understand is that the reason for slavery had nothing to do with "lording it" over another human being but rather to maintain a stable labor force. In other words, without slavery, the planter would be constantly in danger of losing all that he possessed if that labor force simply wasn't available to sow and to reap. Agriculture is a livelihood in which there are periods of intense labor followed by periods of, if not rest, than certainly far less work than is required during planting and harvest. That is why school children in rural areas used to be excused from class during those periods! These were activities that could not be "put off" until a more convenient time. On the other hand, the mill, factory or mine owner needed only to have available to him a labor pool from which to draw workers because one day at the mill, factory or mine was much the same as any other. Most of the jobs in the manufacturing North did not require any great skill or training but they did require bodies in which the manufacturer need not invest anything but a small wage in exchange for hard labor. So the North, with its endless supply of immigrants pouring into its cities, did not need to maintain chattel slavery which was far more expensive as a source of labor than the cheap and easily replaced "wage slave." However, the agricultural South which had no such multitudes fleeing the wars and famines of Europe, found itself wed to a system that had gotten out of control simply because no one no, not even Thomas Jefferson, could determine what would happen, and, more importantly, how to avoid what would happen if the system were simply "ended" and the newly freed slaves released into the general population to fend for themselves. This situation was summed up in Jefferson's agonized response to the call for emancipation: "But what shall we do with the Negro?" This is one of those "pieces" that is most frequently left out of the puzzle of antebellum slavery though it is certainly no secret to historians. The problem is this: they cannot delve deeply into what happened and why it happened and still maintain the claim that the War for Southern Independence was solely a desperate effort to maintain chattel slavery. In addition, they cannot lay the "blame" for chattel slavery entirely at the door of the people and the States of the South. And this is where we find the second "lost piece" of the puzzle; that is, what was happening in the North during this period of time? And to this most important question, I refer the reader to an article written by African-American journalist, Francie Latour. Ms. Latour's work appeared in the September 26th, 2010 edition of the Boston Globe*, hardly a Southern paper. The title of her article is New England's hidden history: More than we like to think, the North was built on slavery. The best thing that could be done would be to post Ms. Latour's article here, but for that we need her permission and having tried to gain such in the past and failing it was determined to try to entice folks to read the piece for themselves through the auspices of this article. Ms. Latour begins with the execution of a black slave who had murdered his master in colonial times. She gives the particulars but does not say where this event occurred until the account is complete. She then goes on to write:

Ms. Latour proceeds to briefly document the history of slavery in New England and the North, something she says has gone too long unrevealed. She also states that, ". . . historians say it is time to radically rewrite America's slavery story to include its buried history in New England." Perhaps that is so, but if it is, I have not seen any effort other than that by Ms. Latour for any such revelations though she solemnly states that all sorts of Northern historians are hot on the trail of Northern slave involvement. As her article was written four years ago and blessed little has come forth on this subject, it would appear that our Northern historians seem less anxious for these revelations than is Ms. Latour. The lady then refers to another extremely interesting book written by three Hartford (Connecticut) Courant journalists, one of whom was Ann Farrow. The book is entitled, Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited From Slavery. This is another work that has received "crickets" from the historical and academic communities. Of course, some effort has been made such as the rather stupid "apology" given by Connecticut for its involvement in black slavery which makes that state, in Ms. Latour's words, ". . . the first New England state to formally apologize for slavery." And while this may assuage the perennially "deeply offended" among us, frankly it is useless until Africa also apologizes and both that Continent and much of Asia and the Middle East end present day slavery! Ms. Latour goes on to quote Stephen Bressler, director of the Brookline (Massachusetts) Human Relations-Youth Resources Commission who said:

Ah, yes, the infamous Triangle Trademolasses to rum to slavesa strictly New England enterprise! Ms. Latour quotes Joanne Pope Melish, a teacher of history at the University of Kentucky and author of the book Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and faced in New England, 1780-1860. Ms. Melish expounds on New England "racism" thusly:

Of course, Ms. Latour could not resist blowing New England's abolitionist horn and brought forth as her hero "The Liberator" William Lloyd Garrison. And, as well, she determines that the whole Civil War (sic) was fought on the issue of slavery. Still, she is honest enough to point out:

The Latour article goes on to remove the romantic notion of a loving, caring culture where whites sympathized and helped the free blacks among them. She quotes historian Elise Lemire who pointed out that, "Slaves [in Concord] were split up in the same way (as slave families in the South). You didn't have any rights over your children. Slave children were given away all the time, sometimes when they were very young." But as interesting as Concord was, historians, according to Latour, say that "Connecticut was a slave state!" Going back to Ann Farrow, the Connecticut journalist, Latour quotes her thusly:

Latour also quotes author C. S. Manegold author of the book, Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North which garnered the same critical "crickets" from academia as did Farrow's Complicity. Manegold argues that New England's "amnesia has not only been pervasive, but willful." In his book, Manegold points to "slavery's markers" that weren't hidden or buried:

Of course, there are many more interesting anecdotes, quotes and revelations in this rather long article and I highly recommend that one not only read the article but the books herein mentioned by Ms. Latour. Far too many Southerners bow beneath the guilt of slavery when they have no reason to do so. Slavery in the South was hardly the horror that we have been told over the years. The proof of that is the fact that by 1861, the black population in the South had reached three million people in the clutches of a genocidal movement tend to lose not gain in numbers. Was slavery a good thing? After the war, when the freedmen were thrown onto their own resources in a desolated South, many was the especially old slave who would have dearly loved to return to his or her cabin and the safety and peace of what had been his or her home. Certainly, the treatment of slaves and free blacks in the North was far worse than in the deepest of the deep South. Ms Latour makes that obvious. Indeed, New York gained the title of a "black graveyard" because of the death rate among that State's black slaves.

Slavery is a very complex issue and especially as it existed in the 19th Century. The idea that an historical situation is being used as a tool for cultural genocide against the People of the South is not only unjust, but mendacious. Those who seek the destruction of all things Southern know perfectly well that they are creating a straw man with which to further their agenda. Neither does it matter whether they pursue that agenda out of ignorance or hatred or the desire for personal gain. A lie must be exposed and confounded or we will all become slaves. When one grows old one tends to resent wasting time and there is nothing that wastes time quite so much as efforts to counter the claims and assertions surrounding the American “Civil War” Of course, the first of these is that the conflict was not a “civil war!” But those who insist upon that label continue to do so despite all demonstrable facts to the contrary. Alas, it is impossible to have reasoned debate when so few are prepared to be reasonable. Indeed, all arguments involving the causes for that war and the subsequent praise and blame devolving upon its participants inevitably lead to the same tiresome claims against the South even when inescapable and acknowledged facts disprove them. In the past the motives and rationale of the Southern States in their efforts to leave the Union were treated with respect—but no more. Now, no good report is ever permitted regarding the efforts by thirteen sovereign States to secede from the compact to which they had voluntarily acceded. The whole thing has deteriorated into the use of the race card. I do not doubt that cultural Marxism in using the issue of race to sow discord in American society has directly led to the present war on the history, heroes and memorials of the South even though Lincoln himself stated unequivocally that slavery was not the reason for his treasonous (Article III, Section 3—United States Constitution) war. But it is useless to counter—however correctly—the current historical orthodoxy simply because apparently no amount of demonstrable “proof” will overcome that deeply desired—and false—narrative. Instead, I call upon an individual whose viewpoint cannot be disparaged because he was a Southerner and owned slaves—because he wasn’t a Southerner, neither did he own slaves! He wasn’t even an American and therefore had “no dog in the fight” as they say. Rather, he was an intellectual giant who dealt with the great matters of the day unhampered by petty political, social or economic opinions. That man was John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton [1834-1902] more familiar to us today as Lord Acton whose comment, “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” is the supreme coherent warning against unbridled power. Described as “the magistrate of history,” Lord Acton was one of the greatest minds of the nineteenth century and is universally considered one of the most learned Englishmen of his time. He made the history of liberty his life's work; indeed, he considered political liberty the essential condition and guardian of religious liberty. After the American war, Acton kept up a correspondence with Robert Edward Lee and it is in one of his letters to Lee that Acton sums up his view of the conflict putting to rest forever all of the petty social, political and economic issues that continue to be used to glorify the federal war and denigrate the South in its efforts to break free from what had become intolerable. In a letter dated November 4th, 1866, Action wrote: “. . . I saw in State Rights the only availing check upon the absolutism of the sovereign will, and secession filled me with hope, not as the destruction but as the redemption of Democracy. . . . I believed that the example of that great Reform would have blessed all the races of mankind by establishing true freedom purged of the native dangers and disorders of Republics. Therefore I deemed that you were fighting the battles of our liberty, our progress, and our civilization; and I mourn for the stake which was lost at Richmond more deeply than I rejoice over that which was saved at Waterloo.” In this letter, Acton makes nothing of all the contentions and assertions as to why what was supposed to be a limited “federal” government had the right to wage war against thirteen sovereign States exercising their constitutional and God given right to leave a compact that had become onerous to them and their citizens. Everything else—every claim, every supposition, every accusation becomes irrelevant in the face of this brilliant man’s clear and concise judgment upon the matter. And for those who demand proof of Action’s conclusion, I suggest that they look at what our “limited” government is today. It is unlimited, corrupt and tyrannous, rejecting the will of the people and embracing “the absolutism of the sovereign will” spoken of by Acton. It is not an accident that the Lincoln Memorial is patterned on the great temples to Zeus erected by the ancient Greeks. Yes, we are still “paying for the Confederacy” but not in the way your article suggests! Because the Confederacy was defeated, today slavery once limited to a relative few in the hands of individual citizens—white and black!—now includes us all in the hands of the Deep State. Many people today—especially those in my age group (I’m 77!)—wonder what has happened to simple commonsense and rationality in the behavior of mankind, especially in the United States and the West. We see what should be regarded as insanity becoming the norm, not just among those whose limited intellect predisposes them to such madness, but even supposedly “enlightened” and “intellectual” folk! Of course, the majority of this lunacy is found on the left, but the middle and the right are not immune either! For ordinary people who retain their sanity, none of this makes any sense. Daily (hourly!) we see behavior that in a better time would have resulted in incarceration for adults and a good hiding for children. Today, it is considered the epitome of civic activism! Some of this can be attributed to the “low-IQ” population but their participation in the current madness cannot explain why it has gone so far beyond that segment of society. Ignorance is, of course, one reason but ignorance can be cured! However, the very segments of society intended to educate and illuminate have become darker in some cases than the “low-IQ” group—and that makes no sense . . . unless you add into the equation, the leftist concept of “utopianism.” This concept has been put forward by the left from its inception, that is, that it is possible for the State to create a utopia on earth, a place where everything is “fair,” and no one is “deprived” and that everyone has everything he or she needs to live a full and happy life. This concept works well in children’s books, but in “real life,” not so much. In the past, the vast majority of the people were intelligent enough to reject the fairy tale but not so today. In the face of indisputable evidence of the failure of socialism and its tenets, people—especially the young—seem to believe that it can be done. All that is required is enough desire and sufficient courage to destroy those who oppose you, and voila’, Paradise Regained! For those who simply cannot understand—or accept—the present situation, there is a cautionary tale that should make all those who deny the truth rethink their faulty conclusions. This is a true story, by the way, though it has all the appearances of a joke! Sad to say, it is not: There was once a minor functionary in the intelligence community (an oxymoron to begin with!) whose only duty consisted of sitting at his desk all day long reading papers that came across it and initialing those papers before sending them on to his superiors. One day, a document arrived at his desk that he knew immediately was far above his pay-grade as they say. However, he followed his instructions, reading and initialing the document and sending it on. Several hours later, his immediate superior arrived at his desk at a dead run exclaiming, “You should NOT have read this document!” He then went on to instruct his subordinate to “erase your signature”—but the instructions did not end there! Instead, his superior (in rank, if not intellect) went on to instruct the man to “signature your erasure!”

Now neither individual here was retarded but victims of a mental process ingrained in today’s people (and not just in the US) where there is a rejection of critical thinking! Obviously, the signature had to be erased to prevent “higher-ups” from learning that an ineligible person had read the document! However, when someone did something in the system, that “something” had to be “signed for!” As a result, action two invalidated action one—and neither man seemed to comprehend that point. This represents a sort of “mental constipation” that simply nullifies ordinary common sense! Furthermore, neither is this situation limited to the “low-IQ” population but is most prevalent among those with more elevated intellects! And this lack of simple, basic commonsense is why we are stumbling forward into the 21st century with little hope that our tomorrows will be better than our yesterdays. |

AuthorValerie Protopapas of New York is a prolific and unreconstructed defender of Southern history and the world authority on the great Confederate partisan John Singleton Mosby. She blogs at www.athousandpointsoftruth.com Archives

March 2022

|

Proudly powered by Weebly