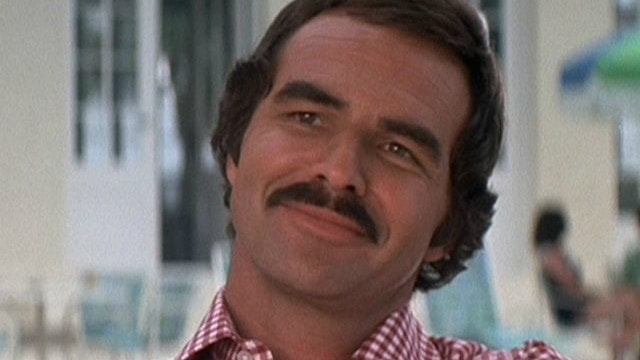

"All you really have in the end are your stories." Burt Reynolds Everyone wanted to be Southern in the 1970s. The rejuvenated interest in Southern music from bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd, Charlies Daniels, and the Allman Brothers (and the unknown Southern influence in the “Motown” sound) was just one component of a larger pro-Southern, working class, populist movement. Southerners had been made consciously Southern again after over a decade of national attention, and the reaction was a positive affirmation of Southern culture and heritage. Hank Williams, Jr. didn’t want “little old danish rolls” he wanted “ham and grits,” but he also understood that “if you fly in from Boston, you won’t have to wait,” but “if you fly in from Birmingham, you’ll get the last gate.” The South could still be the “specimen,” the insignificant curiosity in the “American War.” This cultural revival reached its zenith with Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976 and his brother Billy’s “Redneck Power” brand of comedy. And in film, Burt Reynolds was quickly becoming the leading actor of the South with the 1977 release of Smokey and the Bandit staring Reynolds, Jerry Reed as “Snowman,” and Jackie Gleason as Sheriff Buford T. Justice. Critics never understood why that film was so popular, but Reynolds, who will be celebrating his 82nd birthday on Sunday (Feb 11), knew that films like Smokey were part of “a whole series of films made in the South, about the South and for the South.” One historian has disparagingly called these films “hick flicks,” and Reynolds stared in several in the decade before Smokey became a cult hit. He often teamed with Reed in these good-natured, though sometimes dark, romps through the South. Reynolds also starred in Deliverance, which along with Easy Rider ranks among the worst portrayals of Southern culture in mid-twentieth century cinema. He corrected that mistake in little known works like White Lightning, Gator, and W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, along with the aforementioned Smokey trilogy. Reynolds lived most of his early life in Florida and was a star running back for Florida State University. Reynolds admired Southern culture and the names of the characters in his films (some of which he either produced or directed) reflected an appreciation for all things Southern, particularly the working class South: Gator McKlusky, Bama McCall, Dixie, Leroy, Butterball, Bo, and Cledus. Even his character in The Longest Yard is distinctively Southern. It might be easy to deride these rolls as caricatures of Southerners, but Reynolds never lost the art of faithful comedy and the ability for Southerners to poke fun at themselves with a hint of dark seriousness and pride. Good Southern comedy had always contained a bit of human failing as an essential component of the Southern experience. Southern heroes aren’t marble or cast iron men, and the imperfect, working class hero who sometimes lives on the fringes of (Yankee) law–or even outright rejects it–is part of Southern folklore and tradition. A moonshiner like Gator McKlusky could become a working class hero like Fireball Roberts or Junior Johnson. Even Lee and Jackson had a humanism that all Americans found moving. This is why Davidson wrote Lee in the Mountains and why O’Connor could pen A Good Man is Hard to Find. Film is an important part of Southern culture, and for about twenty years, no one was more recognized as the face of the South in Hollywood than Burt Reynolds. Here’s to Gator McKlusky. This piece was originally published on the Abbeville Institute website on February 9, 2018.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorBrion McClanahan is the author or co-author of five books, 9 Presidents Who Screwed Up America and Four Who Tried to Save Her (Regnery History, 2016), The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Founding Fathers, (Regnery, 2009), The Founding Fathers Guide to the Constitution (Regnery History, 2012), Forgotten Conservatives in American History (Pelican, 2012), and The Politically Incorrect Guide to Real American Heroes, (Regnery, 2012). He received a B.A. in History from Salisbury University in 1997 and an M.A. in History from the University of South Carolina in 1999. He finished his Ph.D. in History at the University of South Carolina in 2006, and had the privilege of being Clyde Wilson’s last doctoral student. He lives in Alabama with his wife and three daughters. Archives |