|

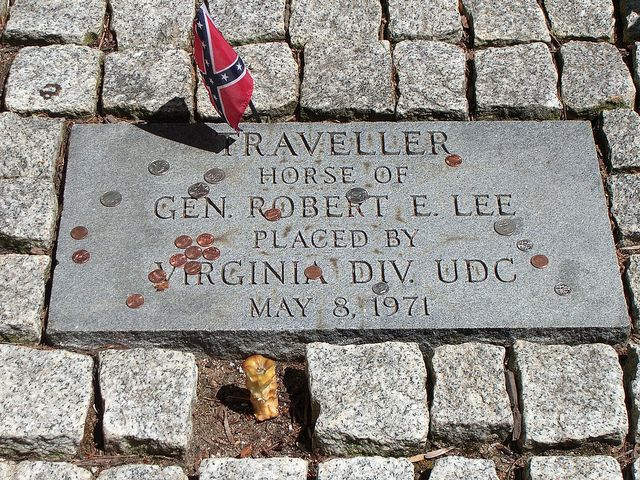

The following is the text of a letter sent to Lynn Rainville, theDirector of Institutional History at Washington and Lee on July 18, 2023. It has been brought to my attention that the Lilliputian grave desecrators at your once-revered institution have now stooped to a level even below that which I thought anyone would go by desecrating the gravestone of a horse! It seems blatantly obvious that the romance of the Civil Rights movement – running out of victims of society to champion – has degenerated into this. Who were the noble perpetrators? Was it some of your purple-haired, nose-ringed, man-bun coiffed, sleeve-tattooed “social justice warriors” among your spoiled brats? Was it some of your milquetoast administrators? Or was it some of your Marxist faculty on their Maoist “Long March” to level society into its lowest common denominator so as to atomize it for the foundation of a totalitarian government?

Whoever it was, they are not fit to apply hoof oil to Traveller’s hooves, or to muck out his stall, much less to lick the boots of his master, for as Thomas Carlyle said, it takes men of worth to recognize worth in men. You all remind me of an observation made by Admiral Raphael Semmes, CSN: “Live asses will kick at dead lions.”

2 Comments

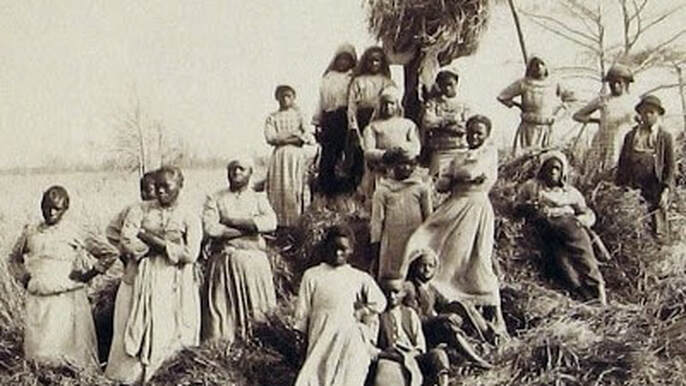

Soldiers, march! We shall not fight again The Yankees with our guns well-aimed and rammed -- All are born Yankees of the race of men And this, too, now the country of the damned … - Allen Tate, “To the Lacedemonians” (1) A rat hole will let in the ocean. - John Randolph of Roanoke (2) Thomas Carlyle said that it takes men of worth to recognize worth in men (3). Among the many worthy men across Western Civilization who recognized the worth of General Robert E. Lee was Sir Winston Churchill who summed it up, saying Lee was one of the noblest Americans who ever lived and one of the greatest captains in the annals of war (4). But now the Lee Monument in Richmond has been taken down by mobs of rioting Harpies, leaving only the towering, vandalized base upon which it rested. That, too, has been dismantled by groveling Governor Ralph Northam, who, loving his office more than his honor, said that Lee no longer represented the values of Virginia. Judging by the filthy graffiti that desecrated the Lee Monument before it was taken down under police presence to the cheers of the mob, I would say no truer words have ever been spoken. What remains is a monument to the moral depravity of this Age without a Name. We are in a Marxist revolution. Critical Race Theory merely replaces traditional class warfare with race warfare, with White people - and particularly Southern White people and the conveniently long-dead Confederacy - as the “oppressors” and scapegoats for all the racial ills in Yankee-land. It all began with Abraham Lincoln and his Orwellian doublespeak in his Gettysburg Address. “Government of the people, by the people, for the people” did not perish from the earth when the Southern States through their respective sovereign conventions peacefully withdrew from the voluntary Union of sovereign States. It perished when they were driven back into it at the point of the bayonet. Ever since the Spring of 1864, we Southerners have been on the defensive. No war was ever won on the defensive, but we have spent barrels of ink explaining the righteousness of our Cause, mistakenly confounding the many causes of secession with the single cause of the war, which was secession itself. That, is what the war was “about,” and what we were fighting for was simply our independence from those who would deny it, just as in 1776, when the thirteen (slave-holding) (5) Colonies seceded from the British Empire. Rather than hammering our detractors with this simple Truth, we instead get ourselves into involved defensive explanations that cause their eyes to glaze over, and when “the defense rests,” they calmly look at us and say “Slavery.” It is a political axiom that whenever your opponent gets you to explaining, you have already lost the argument. I take a different approach. I indict the hypocrisy of our detractors and their Myth of American History. The agitation over our Confederate monuments rests upon this fossilized myth, which proclaims that “The Civil War was all about slavery, the righteous North waged it to free the slaves, and the evil South fought to keep them. End of story. Any questions?” Well, yes. I have quite a few. First, to claim that the South went to war to keep their slaves, one must also claim that the North went to war to free them. The simple fact is, that it did not. Abraham Lincoln boldly admitted that fact in his First Inaugural, so my first question to them is, do they expect me to doubt the word of “Honest Abe”? My next question is, if the North went to war to free the slaves, why was slavery constitutional in the United States throughout the entire war? When some of the Northern States abolished slavery for its inutility in their industrializing society, they did not free their slaves. Instead, they sold them South before their abolition laws went into effect (6). But there still were “slave States” in the Union throughout the war, so if the righteous North went to war to free slaves, as the Myth of American History has it, why didn’t they free their own? And why did Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation – issued halfway through the war when the South was winning it – say that slavery was all right, as long as one were loyal to his government? And why did he admit West Virginia, a so-called “slave State,” into the Union six months later? And why did Lincoln – a documented White Supremacist (7) - choose to inaugurate the bloodiest war in the history of the Western Hemisphere to, in effect, drive Southern slavery and four million Southern Blacks back into the Union, when he could have well been rid of them all without firing a shot? Do the grammar school histories indoctrinating our children or the Marxist professors in our highest universities say anything about all this bald-faced hypocrisy of the self-righteous North? In his Second Inaugural, Lincoln claimed that the South was fighting to expand slavery into the Territories (8). That was certainly a political issue before the war, but with the South out of the Union, the Confederacy had given up all claims to the United States Territories, making Lincoln’s specious claim just one more smelly “red herring” to cover the tracks of his murderous usurpation of power in waging his war of invasion, conquest, and coerced political allegiance against the South. But since Lincoln did not recognize the Southern States as being out of the Union (9), by his own definition he was committing treason under Article III, section 3 of the Constitution by waging war against them. Lincoln was the usurper and the traitor, not Jefferson Davis. Secession is merely freedom of association writ large. There were many causes of secession, not least of which that Southerners no longer wished to be associated with those people who slandered, despised, and hated them so. But that begs the question of why those people waged the war to prevent their departure. To hear their vitriol, one would think they would have been glad to be rid of these Southern Apostates polluting what the New England Pilgrim Fathers called their “Citty upon a hill.” But they weren’t, for running like a river beneath their bigoted pieties was their avariciousness. Follow the dollar and know the truth. Quite simply, cotton was “king” in 1861, and the South’s “Cotton Kingdom” was the North’s “cash cow.” With the South out of the Union, the North’s “Mercantile Kingdom” would collapse (10), so Lincoln rebuffed every Southern overture for peace and launched an armada against Charleston Harbor to provoke South Carolina into firing the first shot (11). South Carolina responded to Lincoln’s provocation just as Massachusetts had responded to George III’s provocation at Lexington and Concord. Lincoln got the war he wanted, but it put him into the shoes of George III. As Tocqueville observed in his classic Democracy in America, “If the Union were to undertake to enforce by arms the allegiance of the confederate States by military means, it would be in a position very analogous to that of England at the time of the War of Independence.” (12). Virginia, “The Mother of States and of Statesmen,” stood solidly for the Union she had done so much to create, but when Lincoln called for her troops to subjugate the Southern States, Virginia refused, indicted Lincoln for “choosing to inaugurate civil war” (13), seceded from the Union, and joined the Confederacy. Four other States – including occupied Missouri - followed her out. But after four years of arduous service, as General Lee said at Appomattox, the South was compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources (14), and Lincoln drove the Southern States back into the Union at the point of the bayonet. Although John Wilkes Booth made a martyr out of America’s Caesar, Reconstruction cemented his conquest. With an Army of Occupation and the pretense of law, and with the Union Leagues stirring up racial hatred and putting the South under Negro rule, a corrupt Northern political party transformed the voluntary Union of sovereign States into a coerced Yankee Empire pinned together by bayonets. The conquered Southern States, accepting the situation at the behest of General Lee, sent their representatives to Congress in December of 1865, but they were not allowed to take their seats. Vindictive Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania stated: “The future condition of the conquered power depends on the will of the conqueror. They must come in as new States or remain as conquered provinces. Congress … is the only power that can act in the matter… Congress must create States and declare when they are entitled to be represented… As there are no symptoms that the people of these provinces will be prepared to participate in constitutional government for some years, I know of no arrangement so proper for them as territorial governments. There they can learn the principles of freedom and eat the fruit of foul rebellion…” (15) In that session, the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery in the United States, was proposed, sent to the States, and ratified – three years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. The Fourteenth Amendment was then proposed. It barred all ex-Confederates from Federal and State offices, and it required the Southern States to share in the payment of the Union war debt and repudiate their own. Tennessee ratified, but the ten ex-Confederate States that rejected it lost their identities in March of 1867 with the passage by Congress of the First Reconstruction Act, which cemented Radical Republican control of the government (16). The Reconstruction Act of 1867 put the ten Southern States under martial law and divided them into five military districts, with Virginia being designated as “Military District Number One.” It enfranchised Southern Blacks (but not Northern Blacks) and stipulated that each Southern State frame a new constitution that met with Yankee approval. This was to be done by a convention consisting of male delegates “of whatever race, color, or previous condition” - with the exception of all Confederate soldiers and most other Southern White men, all of whom were disfranchised. Then, when the new legislature elected under this new constitution had ratified the proposed Fourteenth Amendment, that State would be “readmitted into the Union” with representation in Congress. But if these States were out of the Union and under martial law, how could they ratify an amendment to the Constitution? And if they were in the Union, how could they be compelled to ratify it? The answer, of course, is Federal bayonets. Reconstruction was as much a calculated revolution as the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, freeing slaves, then enslaving free men to a totalitarian government – a government entirely in the hands of the North. Results? For the North? “The Gilded Age.” For the South? Grinding poverty in a land laid waste for a hundred years and the curse of being ruled by little men. For the Blacks? A recent study of military and Freedman’s Bureau records has revealed that between 1862 and 1870 perhaps as many as a million ex-slaves, or twenty-five percent of the population, died of starvation, disease, and neglect under their Northern “liberators”! (17) This was more than the total of Union and Confederate soldiers killed in the war. Freed from their master’s care, “Father Abraham, The Great Emancipator,” had told the Blacks to “root hog, or die.” The enfranchisement of Blacks in the South (but not in the North until the ratification of the XV Amendment in 1870) was not due to any Northern altruism, as The Myth of American History would have us believe. It was merely a cynical Northern political tool to make the Southern States Republican and cement the North’s conquest. Once she had achieved it with her so-called “Reconstruction,” the North abandoned her Black puppets to the upheaval she had wrought in Southern society and turned her attention to the Plains Indians, who were in the way of her trans-continental railroads. But that’s another story - let the Indians tell you that one. The gradual reconciliation after Reconstruction came in part from the South’s “acceptance of the situation,” and in part from the North’s recognition of the South’s difficulty in suddenly assimilating millions of Africans into Western Civilization. Since the North had gotten all that she wanted – which was unfettered control of the Federal Government - she was content to let the South deal with that problem. However, when Southern Blacks started moving North to the Promised Land, they found themselves relegated by a cold Northern racism into segregated ghettoes and discovered that the Northern rhetoric about social equality was a political sham. The invention of television gave Northern politicians a way out of this embarrassing situation by giving them the means to divert Black attention from de facto Northern segregation onto the codified segregation in the South, but their demagoguery provoked race riots up North. Desperate, guilt-ridden Northern White Liberals were driven to devise further crusades upon which to divert the attention of their unwanted Black population onto Southern scapegoats. First came the “Freedom Riders” – locked arm-in-arm with Black marchers – protesting Southern segregation and posting their Progressive virtues before the TV cameras for all to see. But while they were delivering tutorials on proper race relations to the benighted Southerners, the Blacks up North were burning their cities down - and they have been doing so ever since, forever compelling Desperate White Liberals to devise new crusades upon which to post their virtues. Their latest crusade is against Confederate Monuments. But when all Confederate monuments have been vandalized and torn down, what will their next targets be? Be assured that these self-righteous, Latter-Day Puritans will not rest, for crusading, witch-burning and virtue posting are in their DNA. It came over in the Mayflower. Meanwhile, Monument Avenue in Richmond is a desecrated shambles; Thomas Jefferson is under assault at UVA; W & L has repudiated General Lee; and VMI has repudiated “Stonewall” Jackson, while her Cadets who fought and died at the Battle of New Market and are buried at VMI have become not only an embarrassment, but a rebuke! But not to worry - when all the Confederate monuments in the South have been torn down, peace, love, and diversity will flow like a river from Minneapolis and Seattle to Chicago and Philadelphia, and Desperate White Liberal Crusaders will be anointing themselves before the TV cameras all across Yankee-land. Meanwhile, as the mania for Equity for every conceivable definition of race, gender, and species reaches beyond the point of absurdity in the Victimhood Olympics, we have been carried away into Babylon, with women being sent into combat, while men push baby buggies around town; with the government funding infanticide and sex-change operations, while girls become Boy Scouts and men “choose” to be women; with children “deciding” their gender and being given access to the bathroom of their choice in school, while anarchy rules the classrooms and teachers are being assaulted by their students without redress; with government schools turned into Marxist indoctrination centers where Critical Race Theory is taught as history and transgenderism is promoted as the norm, while conservative speakers at colleges are being hounded off campus by Antifa and Black Lives Matter mobs; with race-norming instead of merit and SAT scores determining college admissions, while grading in classwork is being abolished as “racist”; with laws being made to conform to barbaric behavior instead of barbaric behavior being made to conform to the law, while convicts are being paroled into society to create racial parity in prisons and the defunded and demonized police are throwing down their badges in disgust; with the National debt approaching thirty trillion dollars and the US Government running riot with it like a teenager with his daddy’s car keys and a bottle of whisky, while inflation runs rampant and the homeless are begging on every street corner for the increasingly more worthless dollar; with a totalitarian government bankrupting businesses and threatening free citizens with draconian penalties if they don’t take the covid-19 vaccine, while the Third World is swarming across the open borders unchecked and unvaccinated… As one commentator said recently, we have become so openminded that our brains have fallen out. Do not hope to reason with these people, for trying to reason with them is like singing hymns to a fence post with a boom box perched on top of it blasting gutter-grunts from some Hip-Hop rapper. If Reconstruction was calculated like the Communist Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917, today’s “Woke Revolution” is mindless fanaticism like the French Revolution’s bloody Reign of Terror. Perhaps the Confederate monuments will be replaced with the guillotine. Progressives consider the march of history to be a linear march towards a secular Utopian perfection, where the oppressive Laws of God have been repealed. It began with the New England Puritans. While Southerners were following Daniel Boone through the Cumberland Gap these Yankee Utopians were burning witches in John Winthrop’s “Citty upon a hill”; while Southerners were with “Old Hickory” whipping the British at New Orleans, New England Yankees were sitting at home and trading with the enemy; and while Southerners were five hundred miles west of the Mississippi in Texas defending the Alamo, these Yankee Utopians were a hundred miles west of the Hudson in New York, establishing their collectivist, Free-Love communes, and setting themselves up as the standard by which all true Americans should be measured. In this they have been remarkably successful, to the point where today they have the inmates running the Equity Asylum. But as the Preacher says in the Book of Ecclesiastes, “Consider the works of God, for who can make that straight which He hath made crooked?” The righteous “Woke” and their rent-a-thug “Social Justice Warriors” love to claim they are on “The Right Side of History,” but history is not a linear march that will end in a rosy Utopia. It is a cyclic March of Folly where rosy Utopian dreams end in totalitarian nightmares. This article is the Introduction to the book The Woke Revolution: Up From Slavery and Back Again. NOTES 1) Allen Tate, “To the Lacedemonians.” https://www. poemhunter.com/poem/to-the-lacedemonians/ 2) John Randolph of Roanoke, Debates of Va. Conv., 1829-30, 319, in William Cabell Bruce. John Randolph of Roanoke 1773-1833, 2 vols. (New York & London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, The Knickerbocker P., 1922) 2: 204. 3) Thomas Carlyle, Latter-Day Pamphlets, IV: “The New Downing Street” in The Works of Thomas Carlyle, 12 vols., Library ed. (New York: John B. Alden, 1885) 8: 134. 4) Sir Winston Churchill, A History of the English Speaking Peoples, 4 vols. (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1958) 4: 170-3. 5) See the 1790 US Census in Thomas Prentice Kettell, Southern Wealth and Northern Profits (New York: George W. & John A. Wood, 1860) pg. 120. 6) Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2 vols. Trans. Henry Reeve (New York: D. Appleton, 1904) The Henry Reeve text as revised by Francis Bowen (New York: Vintage Books, 1954) 1: 381-2. 7) Lerone Bennett, Jr., Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Co., 2000) pgs. 183-214. 8) Abraham Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address” (1865), in Charles W. Eliot, ed., The Harvard Classics. 50 vols. (New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1910) Vol. 43, American Historical Documents, pg. 451. 9) Ibid, “First Inaugural Address” (1861). Eliot, 43: 336-7. 10) Gene Kizer, Jr., Slavery Was Not the Cause of the War Between the States: The Irrefutable Argument (Charleston and James Island, S. C.: Charleston Athenaeum P, 2014) pgs. 56-69. 11) Charles W. Ramsdell, “Lincoln and Ft. Sumter,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 3, Issue 3 (August 1937) pgs. 259-88, in Kizer, pgs. 197-248. See also John Shipley Tilley, Lincoln Takes Command (Chapel Hill: U of N. C. P, 1941) pgs. 179-87, 266-7, 306-12, with documentation from original sources, including the Official Records. 12) Tocqueville, 2: 425. 13) Gov. John Letcher, letter to Sec. Simon Cameron, April 16, 1861, in the Richmond Enquirer, April 18, 1861, pg. 2, col. 1. Microfilm. The Daily Richmond Enquirer, Jan. 1, 1861 – June 29, 1861. Film 23, reel 24 (Richmond: Library of Virginia collection). 14) “Lee’s Farewell to His Army” April 10, 1865. Eliot, 43: 449. 15) Thaddeus Stevens, “The Conquered Provinces,” Congressional Globe, 18 December 1865, 72, in Walter L. Fleming, ed. Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational and Industrial, 1865 to 1906, 2 vols. (Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Co., 1906) 1: 148. 16) Acts and Resolutions, 39 Cong., 2 Sess., 60, in Fleming, ed. Documentary History, 1: 401-3. 17) Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012) passim. See also John Remington Graham, The American Civil War as a Crusade to Free the Slaves (South Boston, VA: Gerald C. Burnett, 2016) pgs. 10-13. "Live not by lies." - Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Over a year ago I took out the following full-page ad in the Richmond Times-Dispatch: “VMI’s removal of any of her monuments for the sake of an ignoble appeasement is embracing a politically correct lie in violation of her Honor Code and a repudiation of her Cadets who died on the Field of Honor.” Since then, VMI has been falling all over herself to repudiate her noble Confederate heritage for the sake of “taking a knee” to the politically correct lie known as “The Myth of American History,” which claims that the righteous North went to war against the evil South to free the slaves. Lincoln himself, in his First Inaugural, specifically stated that he was not going to war over slavery, but to collect the revenue. Are we to call “Honest Abe” a liar? Cotton was “King” and with the “Cotton Kingdom” out of the Union, the North’s “Mercantile Kingdom” would collapse, so Lincoln rebuffed all peace overtures from the South, provoked the firing on Ft. Sumter, launched his war, and drove the South back into the Union at the point of the bayonet. Follow the dollar and know the truth. The noted historian Barbara Tuchman most succinctly and accurately called it “The North’s War against the South’s Secession.” If the North were going to war to free slaves, why didn’t she free her own? There were slave States in the Union throughout the war. Lincoln issued his famous Emancipation Proclamation as a desperate war measure halfway through it when the South was winning her independence. It had nothing to do with trying to end slavery in the United States. Why else did Lincoln's proclamation state that slavery was just fine as long as one were loyal to his government? Why did he admit West Virginia – a slave-State – into the Union afterwards? And why was slavery constitutional in the US throughout the war? The slavery issue was just the smelly “red herring” dragged across the tracks of a murderous and unconstitutional usurpation of power. “Stonewall” Jackson once owned some slaves. So what? George Washington owned far more slaves than Jackson ever did. What is to be done with his statue, and his arch? Abraham Lincoln, according to Kevin Orlin Johnson’s research in his book The Lincolns in the White House: Slanders, Scandals, and Lincoln’s Slave Trading Revealed, once owned and sold slaves from his father-in-law’s estate, and General Grant owned slaves through his wife’s estate in Missouri all through the war. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, everyone – Blacks included - was complicit in slavery in some way, just as we all are complicit in capitalism today. The US Census of 1830, for example, lists many free Black owners of slaves - from New Orleans to New England. Don’t try to make the South the scapegoat for a world-wide institution as old as recorded history (see Leviticus 25, for example, or the Greek and Roman Classics). That, too, is a lie. The South did not “enslave” anyone. Black Africans captured Black Africans and sold them into slavery to White people in the first place, and Yankee slave-traders brought them over here. According to the January 1862 New York Continental Monthly, New York, Boston, and Portland were the largest African Slave-trading ports in the world at the time of Lincoln’s election. The wealth and prosperity of New England was founded on the African slave trade, and the wealth and prosperity of the North was based upon the manufacture and export of Southern staples. It would be interesting to know if John Brown wore a shirt manufactured from slave-picked cotton when he was hanged. Virginia stood solidly for the Union she had done so much to create, until Lincoln called for her troops to invade the Confederacy. Virginia refused, indicted Lincoln for “choosing to inaugurate civil war,” and immediately seceded. Four other states, including occupied Missouri, followed her out. VMI and her Cadets fought and died to defend Virginia from invasion, conquest, and coerced political allegiance – just as their fathers had done in 1776 when the thirteen (slave holding) colonies seceded from the British Empire. For VMI to repudiate her noble heritage for the sake of an ignoble appeasement based upon a bald-faced lie is a shame and a disgrace. The Great Men of HistoryAs George Washington, “The Father of His Country,” fades into the mists of history along with the voluntary Union of sovereign States, Abraham Lincoln, dominating the Washington Mall in his Olympian Temple just as his Empire dominated Washington’s Republic in 1865, has been anointed “The Great Man of American History.” What part does the so-called “Great Man” play in history and cultural evolution? The answer is double-edged, for it requires an understanding of the distinction between the temporal process of “history” (“a chronological series of events each of which is unique”) and the temporal-formal process of “evolution” (“a series of events in which both time and form are equally significant: one form grows out of another in time.”) (1) G. W. F. Hegel defined the Great Men of History as the “World-Historical Persons whose vocations it was to be the Agents of the World-Spirit.” (2) If the “World-Spirit” is deduced here as being the impulse of evolution towards the culmination of its pattern, then we must look to this distinction between history and evolution to place the Great Man in his proper context. The course of history – being a temporal process of unique events – can be determined as much by, say, the random act of an idiot or by Missus O’Leary’s cow as by the deliberate act of a Great Man. The course of evolution, on the other hand, is a different matter. While we may hope that the course of history determined by the act of the Great Man is different from that determined by the act of a particular cow or a particular idiot, neither he nor they can determine or control the course of cultural evolution. What the Great Man can do and does do, however, is to ride the crest of evolution as a navigator or a pilot and obey the imperatives of his culture, an “unconscious impulse that occasion(s) the accomplishment of that for which the time (is) ripe.” (3) This is what distinguishes him from Missus O’Leary’s cow. But it is not enough for him only to be a man of great capacity; he must also have a crest to ride. He must live in conjunction with, and respond to, the culmination of a cultural pattern of evolution; otherwise he will be lost in obscurity. These “World-historical-men,” therefore, are world-historical because they “met the case and fell in with the needs of the age.” (4) The man, then, does not determine the age; it is the age that calls forth the man. Had Abraham Lincoln been born ten years earlier or ten years later, America might never have heard of him. Great Men and the Age of the Machine:Abraham Lincoln rode the crest of the Industrial Revolution in America, a revolution that transformed an age that had begun when Adam and his sons stepped out of the Garden of Eden and learned the domestication of plants and animals. The Age of Agriculture ended in the nineteenth century with the development of technology that could effectively harness solar energy from fossil fuels. With this revolution, steam power replaced muscle power as the prime mover of civilization, and the Machine Age was born roaring. The amount of energy harnessed by the Industrial Revolution and the efficiency with which it was put to use increased exponentially as technological evolution synthesized, resulting in the rapid growth and the increasing complexity of social structures to orchestrate it all. As the means and the efficiency of harnessing the free energy of the cosmos increased, populations in the industrializing cultures doubled and in some cases nearly tripled during the nineteenth century. The rural, aristocratic, agrarian feudal system became obsolete and was replaced by an urban, parliamentary, production-for-sale-at-a-profit economy, while the ideologies, values, beliefs, morals and myths of the industrializing cultures evolved apace to justify it all. With the great increase of population and cheap labor, and with the increasingly complex demands of industrialism, slavery and serfdom were found to be inefficient labor systems and they were abolished. While the basic dichotomy of the class structure remained, the composition of these classes underwent radical change. As Leslie A. White says: “Industrial lords and financial barons replaced the landed aristocracy of feudalism as the dominant element in the ruling class, and an urban, industrial proletariat took the place of serfs, peasants, or slaves as the basic element in the subordinate class. Industrial strife took the place of peasant revolts and uprisings of slaves and serfs of earlier days.” (5) White makes an interesting observation of cultural evolution and its technological determinant: as culture evolves the rate of growth is accelerated. As technology synthesizes at an ever-increasing pace in our day, culture, like cancer, is metastasizing – but whether into a single global state or into a state of global frenzy remains to be seen. Meanwhile, we have unlocked the energy of the atom, and again a new revolution is upon us, this time superimposed upon the old. In addition, with the evolution of digital technology, of the internet, of the ubiquitous hyperventilating of the media dunning us day-in and day-out, and of the instant global communications between everyone from kings, priests, and tyrants, to radicals, peasants, and demagogues, social structures are being radically transformed all over the world. Whether this new wine can be contained in an old wineskin remains to be seen. We are indeed “riding the stream of Time,” as Bismark said (6), but any claims of control over it are sounding increasingly more like an anthropocentric whimper. This realization should not be taken as defeatist. If we are discovering that we cannot control the course of evolution, then we must learn to adjust to it the way a sailor must adjust to the weather and to the conditions of the sea – conditions that he cannot control. In order to adjust to the course of evolution we must learn to predict it like we predict the weather, and, with the experience of a seasoned pilot, learn to “read the river” for its rocks and shoals, its tides and its currents. To predict the course of evolution, a study of the history of those who have ridden this “River of Time” before us is necessary. And as the accurate marking of channels and hazards is vital if our river chart is to be worth anything, then we must sift history for the Truth. Only then – and with an attitude of humility before the might of the Infinite - may we hope to become successful pilots, like the Great Men of History. Notes

Fisher’s Hill, a veritable fortress stretching across the Valley westward from the Massanutten – is a good place to rally from the good fight with Sheridan, whose cavalry alone outnumbers Early’s entire army. But a flank march through the woods on the mountain to the left breaks out and rolls up the lines. Ragged, starving, and lice-infested prisoners of war are packed into a long train of wagons and galloped all night down the Valley Pike to Winchester for fear of Mosby’s men. A doctor volunteers his services in “the war to make the world safe for democracy,” but he is not needed there because he has a family, and his services are more needed at home. A surgeon makes three invasions, and, building shelters for his wounded with pine boughs in the snow, refuses orders to withdraw from the Hertgen Forest and is killed by artillery fire while helping to carry a stretcher. An Infantry officer in Burma helps to repel an attack at night, and attackers fall at his shots. “Oh, no, son. You mustn’t say that. That man may have had a little boy just like you waiting for him to come home.” An Engineer officer in Vietnam, riding in a jeep and escorting a crippled bulldozer on a lowboy through a village near twilight, meets a man by the side of the road in a conical peasant’s hat, shorts, open shirt, barefooted, and feet planted solidly into the ground. For a moment their eyes meet – the eyes of the rash, parvenu West, the energy of the bright and lusty cities clamoring day and night for more steam, more steel, more trade, more wealth, and more power looking into the eyes of the eternal East, the blade of grass that pushes up through the cracked-pavement entropy of mean streets and litter-strewn alleyways, of desolate factories and drug-plagued ghettoes, of gang wars in crumbling concrete wastelands, the patient blade of grass that waits like the grave for its victory. The East does not blink, and Sheridan’s cavalry passes on. A deadly drone strike against civilians caps a withdrawal from Afghanistan, “The Graveyard of Empires.” The Editor of the Roanoke Times has a bee in his bonnet to get something named for John C. Underwood (1). Underwood was a US District Judge in Virginia during Reconstruction who was to preside over the trial of President Jefferson Davis before charges were dropped by the US Supreme Court, and who did preside over the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867. He was described as a “semi-”carpetbagger, as he had resided in Virginia for a time prior to the war (2). Personally, he has been described as “repellant; his head drooping; his hair long; his eyes shifty and unpleasing, and like a basilisk’s...” (3) Underwood was a native of New York who moved to Northern Virginia several years before the war, and had a farm in Clarke County, but he was a radical abolitionist and got run out of the State. During the war he returned under the protection of Governor Francis H. Pierpont’s Unionist government, where he was appointed US District Judge (4). Pierpont’s “government,” founded by the Wheeling Convention early in the war and consisting of Pierpont as “governor” with three senators and nine delegates as the “General Assembly,” and ensconced in Alexandria across the river from Washington, was recognized by Lincoln, giving him “Virginia’s” electoral votes in 1864, as well as the votes of “West Virginia,” a new state separated from Virginia with the permission of the Pierpont government. After the war, the Pierpont government moved to Richmond, and Underwood went with it. In 1867, under the Reconstruction Acts, the Southern States lost their identities and were placed under martial law and an Army of Occupation, (Virginia being designated as “Military District No. 1,”) and all Confederate soldiers and any who gave aid to the Confederacy disfranchised (5). Blacks, on the other hand, were enfranchised (but not in the North) and under the control of the carpetbaggers and their Union Leagues, who taught them how to hate, and to vote the Radical Republican ticket (6). Confederate President Jefferson Davis had been vindictively enchained at Fortress Monroe for the two years since the war. He was supposed to die there, but he did not. He was then supposed to be hanged for treason by military tribunal but he was not, as the civil courts had resumed jurisdiction (7). In the Spring of 1867, Judge Underwood was to bring him to trial in Richmond with a jury he selected. Perhaps more in the prevailing spirit of Northern vindictiveness rather than for any altruistic solicitude for civil rights, Underwood seated Blacks on the jury and, abandoning all regard for judicial decorum, harangued them with inflammatory lies against the Confederacy. “The Confederates had been motivated by the ‘fiery soul of treason.’ Southern ‘assassins’ had been guilty of murdering Federal prisoners of war deliberately by starvation; of practicing germ warfare by scattering yellow fever and smallpox germs among helpless civilians; of striking down Abraham Lincoln, ‘one of the earth’s noblest martyrs of freedom and humanity’...” etc. (8) The editor of the Roanoke Times accuses the Virginia textbooks from the 1950s of “indoctrinating schoolchildren.” With the truth, perhaps, instead of with “The Myth of American History,” as now. Of course no charges of indoctrination could conceivably be made against newspaper editors at the Roanoke Times – pure and pristine as the new-blown snow as they are – or of their pandering to the mob during the “Woke Revolution” to sell newspapers. As part of the Lee Enterprises News Cabal, headquartered in one of those square-shaped states out there in the Midwest somewhere and answering to Warren Buffett, they could not possibly have any affiliation with The Ministry of Propaganda. But as Tennyson wrote, “they, sweet soul, that most impute a crime are pronest to it, and impute themselves” (9). As for Judge Underwood’s demagoguery, the Confederacy had been motivated not by “the fiery soul of treason,” but by the same desire for independence as in 1776. Scanty rations in Southern POW camps were the same scanty rations that starving Confederate soldiers subsisted on, and Union POW deaths were due to the North’s refusal to exchange prisoners. In fact, according to the Official Records, the mortality rate among Confederate POWs in Northern camps was higher than the mortality rate among Union POWs in Southern camps (10). As for Underwood’s charges of germ warfare, it is on record that between 1862 and 1870 perhaps as many as one million freedmen, or twenty-five percent of the population, died or were in mortal peril from starvation, epidemics and neglect under the hands of their Northern “liberators” (11). As for the assassination of Lincoln, the South had everything to lose and the Radical Republicans had everything to gain by it (12). Jefferson Davis was offered a pardon by President Andrew Johnson, but he refused it and demanded a trial. It might have been the most important trial in the history of the United States, but the prosecutors were afraid that the uncomfortable facts of the Declaration of Independence and the Tenth Amendment to the US Constitution might come up, Davis would be acquitted, and the North would lose in court what it had won in war. Worse yet, since Abraham Lincoln had never recognized the Southern States as being out of the Union, the embarrassing fact might be exposed that it was Lincoln – not Davis – who was the one who had committed treason under Art. III, sec. 3 of the US Constitution by invading them. So US Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase had the case dropped on a technicality and Davis went free (13). But Judge Underwood was not finished. He was to preside over the Constitutional Convention that met in December of 1867, also known as the “Black and Tan” or “Underwood” Convention. With most White Virginians disfranchised, the delegation was comprised of 32 conservative Whites, and 70 Radical Republicans, which were composed of 25 Blacks, 17 scalawags and native Virginians, 6 from foreign countries, 13 New Yorkers, and the rest carpetbaggers from other Northern States. Some Whites and most Blacks were illiterate (14), fresh from the corn, cotton, and tobacco fields, decked out in silk hats and broadcloth suits, and reading newspapers upside down (15). A White conservative delegate from Augusta County described (among many other sketches of the Convention) Judge Underwood: “The president of the Convention is, apparently, a gentleman of great amiability. When I observed the other day the suavity of his deportment in the chair, and thought of the shocking harangues he was lately wont to deliver to his grand juries, I was reminded of Byron’s description of one of his heroes, - ‘as mild-mannered man as ever scuttled Ship,’ etc.” (16) The Underwood Convention framed a Northern constitution, with secret ballots and an increase in local officeholders at taxpayer expense. It required free public schools and heavy taxes on land, which would compel the disfranchised Virginians to pay for the carpetbaggers’ programs. It gave the right to vote to every adult male who had resided in the State for six months, except those thousands who had been Confederate leaders. And it provided that no one could be an office holder or a juror unless he could swear that he had not supported the Confederacy. The Underwood Convention went on until the per diem ran out, and General Schofield, commander of Military District No. 1, finally compelled it to adjourn in April of 1868 (17), when “The Midnight Constitution” came into birth (18). The editor of the Roanoke Times wants to have something named after John C. Underwood to pay him “tribute.” A portrait of his character by one who was knowledgeable of him at the time of the opening of Jefferson Davis’ trial in Richmond is offered here: “Reporters for Northern papers were present with their Southern brethren of scratch-pad and pencil. The jury-box was a novelty to Northerners. In it sat a motley crew of negroes and whites. For portrait in part of the presiding judge, I refer to the case of McVeigh vs. Underwood, as reported in Twenty-third Grattan, decided in favor of McVeigh. When the Federal Army occupied Alexandria, John C. Underwood used his position as United States District Judge to acquire the homestead, fully furnished, of Dr. McVeigh, then in Richmond. He confiscated it to the United States, denied McVeigh a hearing, sold it, bought it in his wife’s name for $2,850 when it was worth not less than $20,000, and had her deed it to himself. The first time thereafter that Dr. McVeigh met the able jurist face to face on a street in Richmond, the good doctor, one of the most amiable of men, before he knew what he was doing, slapped the able jurist over and went about his business; whereupon, the Honourable the United States Circuit Court picked himself up and went about his, which was sitting in judgment on cases in equity. In 1873, Dr. McVeigh’s home was restored to him by law, the United States Supreme Court pronouncing Underwood’s course ‘a blot upon our jurisprudence and civilization’” (19). So name something after John C. Underwood, or perhaps build him a monument on the Capitol grounds. He is of low degree but eminently worthy of our times, and the carpetbaggers and the scalawags who have overrun Virginia are in need of love, too. But know that it takes more than a zip code to make a Virginian. Notes

If you are like me, you probably don’t spend a lot of time thinking about mules these days, but a passage from Faulkner brought them to mind. Collectivism so far has not taken root in the South, but things are so rapidly changing with the “Woke Revolution” there is no telling the future. But whatever the future holds, the “woke” will have to contend with the ubiquitous individuality of the native Southerner, and one of the most individual of that breed is the mule. As William Faulkner wrote in Flags in the Dust: Some Cincinnatus of the cotton fields should contemplate the lowly destiny, some Homer should sing the saga, of the mule and of his place in the South. He it was, more than any one creature or thing, who, steadfast to the land when all else faltered before the hopeless juggernaut of circumstances, impervious to conditions that broke men’s hearts because of his venomous and patient preoccupation with the immediate present, won the prone South from beneath the iron heel of Reconstruction and taught it pride again through humility and courage through adversity overcome; who accomplished the well-nigh impossible despite hopeless odds, by sheer and vindictive patience… As a city boy growing up in Lynchburg right after the Second World War, I didn’t have much occasion to come into contact with mules. My father had come home and was a manufacturer’s representative for a farm machinery company, but he told me they still used mules in the tobacco fields, pulling the sleds down the rows where a tractor couldn’t go. Most of those broad tobacco fields that I remember seeing below Lynchburg when we were driving to South Carolina to visit my grandparents are gone now, and the mules with them, too, I suppose. I remember one day in South Carolina seeing a car load of colored men in an old car, with one leaning out of the window leading a mule trotting alongside, with harness jangling, in a picture surely worth a thousand words. My long-time “ol’ podner” Doug Wakefield (may God rest his soul) grew up in the little town of Iva, South Carolina. In an early manifestation of his innate patriotism – before serving two tours of duty in Vietnam with the Navy – he was a member of the Civil Air Patrol. He said on Sunday afternoons they would muster on the roof of Claude Finley’s mule barn to watch for Communist airplanes. Finley’s mule barn was the tallest structure in town, and CAP “intel” had evidently determined that a Communist strike on his establishment – the largest mule distributorship in the South - was likely most immanent on Sunday afternoons after church. I recently attended a funeral in Iva, but I saw no sign of any mule barns in the growing town or its environs. Mules, horses, and oxen were the farm tractors before steam power replaced muscle power as the prime mover of civilization, and they carried history on their backs. In my front yard when I was growing up, there was a swale over which my tire swing hung. It was part of the remnant of General Jubal Early’s defenses of Lynchburg in 1864 when the Yankees came - the old road that connected Ft. McCausland on Langhorne Road with the redoubt held by the Lynchbug Home Guard – “The Silver Grays” – and the VMI Cadets up on Rivermont Avenue, where Villa Maria is now. My father rigged up my tire swing for me. He tied a chisel to the end of a heaving line, threw it high up over a limb on the big oak tree, bent the end of the heaving line to the main line for the swing, pulled that over the limb, tied a slip knot, pulled it taught against the limb, and secured the other end to the tire. Then he cut a drainage hole in the bottom of the tire and I was “good to go” (except for the wasps that you had to watch out for that would build a nest in the tire) getting a good running start and swinging out over that little depression in the front yard where ninety years before teamsters pulling wagons, and artillerymen pulling guns and caissons cracked whips and swore at hard-headed and recalcitrant mules: … Father and mother he does not resemble, sons and daughters he will never have; vindictive and patient (it is a known fact that he will labor ten years willingly and patiently for you, for the privilege of kicking you once); solitary but without pride, self-sufficient but without vanity; his voice is his own derision. Outcast and pariah, he has neither friend, wife, mistress nor sweetheart; celibate, he is unscarred, possesses neither pillar nor desert cave, he is not assaulted by temptations nor flagellated by dreams nor assuaged by visions; faith, hope and charity are not his. Misanthropic, he labors six days without reward for one creature whom he hates, bound with chains to another whom he despises, and spends the seventh day kicking or being kicked by his fellows… After The War, there were the “forty acres and a mule” that the carpetbaggers had promised the freedmen in exchange for their votes. It worked pretty good for the carpetbaggers, but not so good for the credulous freedmen. While they got top hats and cigars, the carpetbaggers got the votes and the forty acres. What they did with the mules is not recorded. They did not need mules to plow the ground for votes, or to harvest taxes, or to foreclose on the forty acres. It front of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts – before Monument Avenue was desecrated and the Confederate monuments were vandalized and torn down – there stood a sculpture of a war horse. He was gaunt and starving, saddled with a McClellan, and with head drooping, worn to a frazzle. The new carpetbaggers and scalawags of the VMFA evidently felt that he looked too much like a Confederate horse, so to placate the tender sensibilities of the “woke” who abound these days, the War Horse was moved around back, lest he offend anyone, and the front of the museum is now graced with Kehende Wiley’s barbarian thug on horseback, “Rumors of War,” created by the artist to mock the “Jeb” Stuart monument (now torn down) - and unintentionally glorifying, sanctifying and enshrining the highest aspirations that those who adulate it are likely to attain. There has been much talk about the replacements for the monuments on the Avenue that were torn down (the Lee monument has been thoroughly vandalized, but it is still standing, albeit under litigation.) A number of replacement heroes of a “woke” multicultural nature have been suggested, but none that remotely match Lee and Jackson for shaking the Lincoln Empire to its foundation while Jeb Stuart rode circles around it in defense of our independence. I don’t know how “woke” he is, but may I suggest a monument to the multi-cultural mule? On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure to weaken Confederate defenses and to keep England or France from recognizing the Confederacy and lifting the blockade of the Southern Coast. It stated in effect that slavery was alright as long as one were loyal to his government, but that those slaves behind Confederate lines were declared “then, thenceforward, and forever free” (1). The war did not end at Appomattox, for there were other Confederate armies in the field, and E. Kirby Smith did not surrender the Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi until June 2, 1865, at Galveston, Texas (2). Thus, the last slaves under the terms of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation were freed there on June 19, but slaves in the United States were not freed until the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution in December of 1865. Accounts survive of emancipation during the war. It was not always a “Jubilee.” Edward A. Pollard, editor of the Richmond Examiner during the war, reported, “The fact is indisputable, that in all the localities of the Confederacy where the enemy had obtained a foothold, the negroes had been reduced by mortality during the war to not more than one-half their previous number… In the winter of 1863-64, the Governor of Louisiana, in his official message, published to the world the appalling fact, that more negroes had perished in Louisiana from the cruelty and brutality of the public enemy than the combined number of white men, in both armies, from the casualties of war… The Yankees had abundant supplies of food, medicines and clothing at hand, but they did not apply them to the comfort of the negro, who, once entitled to the farce of ‘freedom,’ was of no more consequence to them than any other beast with a certain amount of useful labor in his anatomy (3)… “We may take from Northern sources some accounts of these contraband camps, to give the reader a passing picture of what the unhappy negroes had gained by what the Yankees called their ‘freedom.’ A letter to a Massachusetts paper said: - ‘There are, between Memphis and Natchez, not less than fifty thousand blacks, from among whom have been culled all able-bodied men for the military service. Thirty-five thousand of these, viz., those in camps between Helena and Natchez, are furnished the shelter of old tents and subsistence of cheap rations by the Government, but are in all other things in extreme destitution. Their clothing, in perhaps the case of a fourth of this number, is but one single worn and scanty garment. Many children are wrapped night and day in tattered blankets as their sole apparel. But few of all these people have had any change of raiment since, in midsummer or earlier, they came from the abandoned plantations of their masters. Multitudes of them have no beds or bedding – the clayey earth the resting place of women and babes through these stormy winter months. They live of necessity in extreme filthiness, and are afflicted with all fatal diseases. Medical attendance and supplies are very inadequate. They cannot, during the winter, be disposed to labor and self-support, and compensated labor cannot be procured for them in the camps. They cannot, in their present condition, survive the winter. It is my conviction that, unrelieved, the half of them will perish before the spring. Last winter, during the months of February, March and April, I buried, at Memphis alone, out of an average of about four thousand, twelve hundred of these people, or twelve a day’” (4). Precise figures are unavailable, but by some estimates, out of a population of four million, as many as 25% of the freedmen perished or suffered mortal peril from epidemic illness and famine from 1862 to 1870 under the hands of their “liberators” (5). In February of 1865, Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stevens tried to negotiate a peaceful settlement to the war with Abraham Lincoln. Stevens asked what the North was prepared to do for the Blacks that the North had emancipated. Lincoln responded, quoting a song then popular: “Root, hog, or die” (6). Perhaps a million did. NOTES:

Hit mus’ be now de kingdom comin’, |

AuthorA native of Lynchburg, Virginia, the author graduated from the Virginia Military Institute in 1967 with a degree in Civil Engineering and a Regular Commission in the US Army. His service included qualification as an Airborne Ranger, and command of an Engineer company in Vietnam, where he received the Bronze Star. After his return, he resigned his Commission and ended by making a career as a tugboat captain. During this time he was able to earn a Master of Liberal Arts from the University of Richmond, with an international focus on war and cultural revolution. He is a member of the Jamestowne Society, the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and the Society of Independent Southern Historians. He currently lives in Richmond, where he writes, studies history, literature and cultural revolution, and occasionally commutes to Norfolk to serve as a tugboat pilot Archives

July 2023

|