|

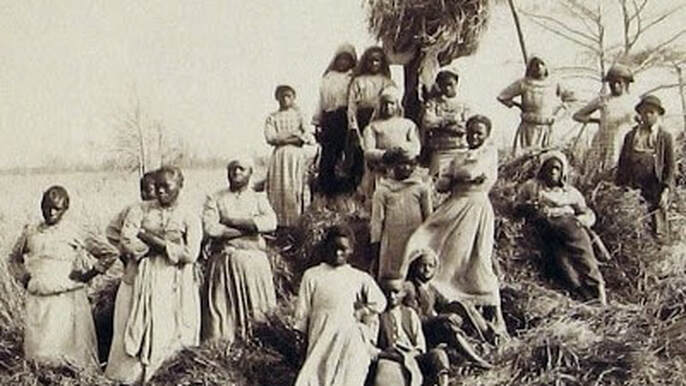

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure to weaken Confederate defenses and to keep England or France from recognizing the Confederacy and lifting the blockade of the Southern Coast. It stated in effect that slavery was alright as long as one were loyal to his government, but that those slaves behind Confederate lines were declared “then, thenceforward, and forever free” (1). The war did not end at Appomattox, for there were other Confederate armies in the field, and E. Kirby Smith did not surrender the Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi until June 2, 1865, at Galveston, Texas (2). Thus, the last slaves under the terms of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation were freed there on June 19, but slaves in the United States were not freed until the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution in December of 1865. Accounts survive of emancipation during the war. It was not always a “Jubilee.” Edward A. Pollard, editor of the Richmond Examiner during the war, reported, “The fact is indisputable, that in all the localities of the Confederacy where the enemy had obtained a foothold, the negroes had been reduced by mortality during the war to not more than one-half their previous number… In the winter of 1863-64, the Governor of Louisiana, in his official message, published to the world the appalling fact, that more negroes had perished in Louisiana from the cruelty and brutality of the public enemy than the combined number of white men, in both armies, from the casualties of war… The Yankees had abundant supplies of food, medicines and clothing at hand, but they did not apply them to the comfort of the negro, who, once entitled to the farce of ‘freedom,’ was of no more consequence to them than any other beast with a certain amount of useful labor in his anatomy (3)… “We may take from Northern sources some accounts of these contraband camps, to give the reader a passing picture of what the unhappy negroes had gained by what the Yankees called their ‘freedom.’ A letter to a Massachusetts paper said: - ‘There are, between Memphis and Natchez, not less than fifty thousand blacks, from among whom have been culled all able-bodied men for the military service. Thirty-five thousand of these, viz., those in camps between Helena and Natchez, are furnished the shelter of old tents and subsistence of cheap rations by the Government, but are in all other things in extreme destitution. Their clothing, in perhaps the case of a fourth of this number, is but one single worn and scanty garment. Many children are wrapped night and day in tattered blankets as their sole apparel. But few of all these people have had any change of raiment since, in midsummer or earlier, they came from the abandoned plantations of their masters. Multitudes of them have no beds or bedding – the clayey earth the resting place of women and babes through these stormy winter months. They live of necessity in extreme filthiness, and are afflicted with all fatal diseases. Medical attendance and supplies are very inadequate. They cannot, during the winter, be disposed to labor and self-support, and compensated labor cannot be procured for them in the camps. They cannot, in their present condition, survive the winter. It is my conviction that, unrelieved, the half of them will perish before the spring. Last winter, during the months of February, March and April, I buried, at Memphis alone, out of an average of about four thousand, twelve hundred of these people, or twelve a day’” (4). Precise figures are unavailable, but by some estimates, out of a population of four million, as many as 25% of the freedmen perished or suffered mortal peril from epidemic illness and famine from 1862 to 1870 under the hands of their “liberators” (5). In February of 1865, Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stevens tried to negotiate a peaceful settlement to the war with Abraham Lincoln. Stevens asked what the North was prepared to do for the Blacks that the North had emancipated. Lincoln responded, quoting a song then popular: “Root, hog, or die” (6). Perhaps a million did. NOTES:

0 Comments

Hit mus’ be now de kingdom comin’, |

AuthorA native of Lynchburg, Virginia, the author graduated from the Virginia Military Institute in 1967 with a degree in Civil Engineering and a Regular Commission in the US Army. His service included qualification as an Airborne Ranger, and command of an Engineer company in Vietnam, where he received the Bronze Star. After his return, he resigned his Commission and ended by making a career as a tugboat captain. During this time he was able to earn a Master of Liberal Arts from the University of Richmond, with an international focus on war and cultural revolution. He is a member of the Jamestowne Society, the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and the Society of Independent Southern Historians. He currently lives in Richmond, where he writes, studies history, literature and cultural revolution, and occasionally commutes to Norfolk to serve as a tugboat pilot Archives

July 2023

|