|

One of the most illogical historical debates I’ve ever tried to follow concerns the personal religious conviction of our founding father George Washington. Presently there seem to be two opposing schools of propagandists. They can be divided more or less into Beckites and Obamaites, and both seem obsessed with Washington’s theological leanings. The generally leftist historian Joseph Ellis is eager to tell us in his relevant work that Washington was not on the evidence a Trinitarian Christian. Although he dutifully attended Anglican-Episcopalian services with his wife Martha, he avoided taking communion after the American Revolution.

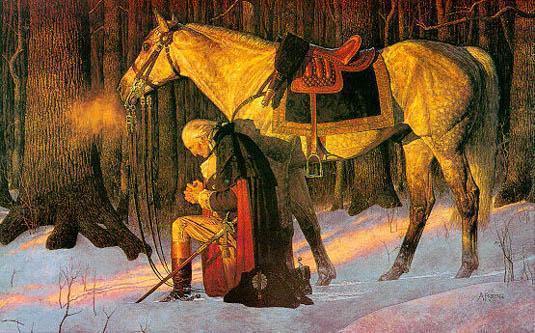

This lack of ritual practice, which was clear to Washington’s minister in Philadelphia (and the local Episcopal bishop), William White, supposedly reveals a great deal about the American founding. Like Jefferson and Franklin, Washington was a free-thinker influenced by the European Enlightenment, and to whatever extent Washington and his fellow founders went along with popular religious enthusiasm, they were simply masking their true feelings. If alive today, they would all no doubt be welcoming the removal of Christian religious symbols from the public square, and in all probability they would be okay with gay marriage and with substituting “holiday greetings” for a “blessed Christmas.” The other side, following Glenn Beck, Sarah Palin, and other authorized “conservative” voices, insist that Washington was a pious Christian, who spent his time in solemn religious meditation. The reason his gravestone and his last will and testament are full of references to Christ as well as to God the Father is that George was, in fact, a believing Christian. Presumably, if still around, our first president would by now would be rallying to the GOP. He might even be on the Glenn Beck show, seated next to Rabbi Daniel Lapin and Martin Luther King’s niece. Here he would join the other guests in decrying abortion and calling for “family values.” In point of fact, the depth of Washington’s Christian beliefs is totally irrelevant to his vision of the country he helped found. It is no more relevant than whether or not Leon Trotsky really believed in Marx’s historical materialism when he led the Red Army. It is only our American obsession with personal authenticity that would cause us to worry about whether Washington was inwardly Christian. This is joined to the equally questionable notion that if Washington did not truly accept the Thirty-Nine Articles of his confession, this lack of faith had profound implications for the republic he helped set up. Such beliefs tell more about the quality of American journalistic debate than they do about the problem of historical impact. From his statements, Washington intended the American people to be religious Christians and allowing for certain exceptions, he probably hoped they would be Christians of the Protestant variety. The fact that he and other founders include in their addresses stern affirmations on the link between religious faith and social virtue indicate they were not smirking at Christian theology, whatever their private reservations. These founders were most emphatically not modern secularists, and Washington was not an exponent of modern democracy. Our first president was a man of the eighteenth century, who believed in the benefits of property relations and gender-specific education, and, perhaps above all, as he tells us in his Farewell Address as president, in the public need for religious beliefs. In these respects, he was little different from the English monarch his countrymen broke from during the Revolution. His proclamation of the first Thanksgiving holiday in October 1789 was most certainly not about celebrating democracy, which is a false connection that U.S. presidents since Lyndon B. Johnson have drawn. It was a defense of ordered liberty in a society in which God “would incline the hearts of the citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to government and entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another and the citizens of the United states at large.” We citizens are urged “to demean ourselves with the charity, humility and pacific temper of mind which were the characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed religion.” There is no need to contrast these tempered passages to President Obama’s most recent Thanksgiving dithyramb, with its homage to Native American enrichments and to “our fledgling democracy,” to grasp the utterly transformed public purpose now assigned to Thanksgiving. Since the 1960s this holiday has become closely identified, perhaps most grievously by Bush II, with a democratic liberating mission and with celebrating the democratic progress of our global society. But the original proclamation, which came from Washington and may have been edited by Bishop White, bears no resemblance to current justifications for Thanksgiving. Moreover, even the decision of Lincoln in October 1863 to establish a yearly commemoration of the Pilgrims’ arrival in New England, an act prompted by the desire to link the nation’s birth to pro-Union New England rather than to Confederate Jamestown, does not really change the significance of Washington’s holiday. Even in 1863 during a fratricidal war, the U.S. and its leaders continued to view the country in some sense as it had in Washington’s time. (Lincoln too was not a regular churchgoer, but his oratory is bathed in Old Testament phrases and Calvinist laments about the wages of sin.) But Washington is explicit in calling for citizens to subordinate themselves to others. What he had in mind was probably a local constabulary and not, in any case, a modern welfare state. His language about authority issues straight out of Paul’s Letter to the Romans, while in the second paragraph there is an Old Testament citation from the prophet Micah. Washington also commends “our blessed religion,” which presumably is not an early allusion to Kwanzaa. It is indeed hard to think of how any president today could draft such a proclamation, even transposed in the appropriate gobbledygook, without being attacked for hate speech. Current attempts to understand the social-religious view of eighteenth-century Virginia gentlemen by relating them to modern-day fixations are an infantile project. The most we can hope to do by making comparative studies is to understand how different the past was from the present. Washington was no more a precursor of our egalitarian, post-Christian times than he was Donald Duck. And he could easily entertain theological doubts without wishing to hand over his country to cultural radicals, and especially not in a government that he would no longer have recognized as his. Equally important, his understanding of religion was anchored in non-modern social concepts, like deference and authority. Washington may have been the commander who finished the work begun with the Tea Party in 1773. But his solution in the end was as stately as the man himself and the holiday he proclaimed.

0 Comments

|

AuthorPaul Gottfried is the president of the H.L. Mencken Club, a prolific author and social critic, and emeritus professor of humanities at Elizabethtown College Archives |

Proudly powered by Weebly