|

"Why would I? I’m a Black man living in the former capital of the Confederacy. I knew what these monuments meant. I always believed they had no place on a grand boulevard." Levar Stoney On Wednesday, July 1, 2020, Richmond Virginia’s Mayor Levar Stoney introduced an ordinance to the City Council calling for the removal four of the monuments to Confederate heroes that together with the famous equestrian Robert E. Lee monument lined the capital’s historic Monument Avenue historic district. Using the public emergency clause, Stoney and the majority of the council accomplished what they had set out to do two years prior. Stoney had shared his personal views about Richmond’s monuments to reporter Andrew Lawler stating:

Stoney never clarified just who “they“ were. Nor did the reporter ask him. Later, in a public address, Stoney married the removal of monuments to a broader national racial justice movement, re-animating them and giving them purpose by changing their meaning as well as the motives of the generations of Southerners who built them.

In the statehouse, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, with a speed uncharacteristic of government had Virginia’s strict monument preservation and protection law amended, removing all protection for Civil War- period memorials. Breaking an 1890 agreement between Virginia and the owners of the monument, Northam announce the state was proceeding with the removal of the jewel of all Confederate monuments, the renowned Robert E. Lee monument. A brief survey of history reveals the culture of the North and the Progressive Left became decisively more secular and revolutionary by 2013. That was the year a hashtag became a movement: Black Lives Matter. It began with the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trevon Martin seventeen months earlier. The deaths of two African-Americans in 2014, Michael Brown and Eric Garner took the social justice group to the streets and into the national limelight. The death of George Floyd and these others provided cover for the illegal vandalism and stealing of Richmond’s monuments and many others in the South, Richmond’s five and by the Fall of 2020 another 103 monuments. The first and only previous desecrations of Richmond monuments were by individuals who spay-painted BLM and Black Lives Matter on the Jefferson Davis monument in 2015 and the Robert E. Lee Monument in 2018. To show the difference in the times. In 2015, 39-year-old Joseph Weindl was sentenced to 100 hours of community service and in 2018, the city offered a $1000. reward for the capture of the vandal. In the summer of 2020 while millions of dollars in damage to the five monuments, not a single person was charged or fined. No one could foresee the coming storm. The motionless likenesses of Southern, continued as always to attract both homeowners and tourists alike. And, , statistics showed that the overwhelming number of deaths of black Americans were at the hands of other black Americans and claims that blacks were targeted by police were likewise false. But the BLM cause was picked up by power-seeking politicians, celebrities, and the usual suspects the news media. When a group came to Charlottesville to oppose the removal of the Robert E. Lee memorial, these groups saw the opportunity to once again attack the South, southerners, and their culture. They were met by a not one but two compliant and enabling governors. If there is to be justice for the monuments, and as the culture and political pendulum begins to swing in the opposite and corrective direction, such can be achieved. A knowledge of who is liable, and a history of the events and actions is necessary. The actions first in New Orleans and then replicated in Richmond were legally unprecedented. In such situations, the courts rely on prior cases, law and outcomes. Presently, there is only one legal action related to the removal of Richmond’s Lee monument awaiting the Supreme Court. A case they will unlikely take up pertaining to a breech of an 1890 agreement. The actions by both mayors resulted in very different legal consequences, and as such will require very different legal strategies. The tragic wholesale removal of 108 monuments over the summer of 2022 had its beginning on July 10, 2015 when the Mayor of New Orleans Mitch Landrieu met unannounced with the City Council and requested that they reclassify all four of the city’s great Confederate monuments as “nuisances”, thus setting the stage for their removal. Landrieu did not give a specific reason for his request, but only 25 days prior, a lone white gunman Dylann Roof murdered black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina. Lousiana along with all the former Confederate states, with the exceptions of North Carolina and Florida, had very strict laws to protect their Confederate monuments, including Virginia. Culminating in the burial of confederate soldiers and the erection and dedication of a Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery on July 4, 1914, the nation moved to heal the divide by extending equal respect to soldiers of the South. A century later, New Orleans’ stated his opposition in a speech commemorating the removal of the city’s lee monument.

Later in the same speech, Landrieu attempted to redefine the monuments with an interpretation that was counter to what 57% of Americans polled believed.

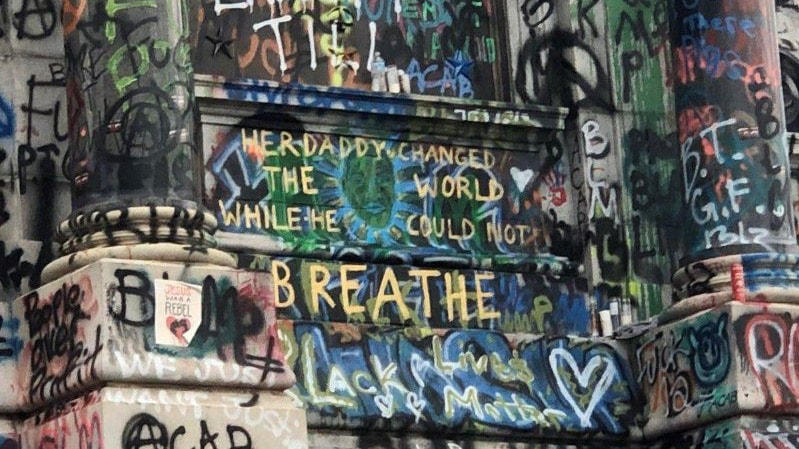

The case against Landrieu and New Orleans’ City Council is both a state and federal matter. Landrieu and the city failed to obey state laws protecting the four monuments removed by city order beginning April of 2017 and ending with the removal of the grand Lee monument and speech on May 19, 2017 (three months before the Charlottesville, Virginia incidents). It can be clearly shown that the majority of Americans had no objections to the Southern monuments and unlike the extreme views of Landrieu, were comfortable with symbols of the South. Just weeks prior to Landrieu request to the council A poll by CNN, conducted between June 26-28 and reported ten days before Landrieu met with the council showed that 57% believed the Confederate flag reflected Southern pride, while only 33% felt it was a symbol of racism. As with the later actions by the Richmond mayor and council, New Orleans officials forced an undesirable outcome and loss for the city and did so by not democratizing the process. So lacking in transparency, the city still refuses to reveal the name of the donor who paid the expense to remove all the monuments. While Landrieu saw the political benefits for crusading against Southern monuments after the Charleston shootings in 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center, saw the fund-raising benefits. SPLC went right to work researching and targeting every monument, memorial and symbol, and even creating a grassroots website to promote their removal and track their success. The website targeting monuments is entitled Whose History Is It? Meanwhile Landrieu goes national with a book tour for his book on the subject, promoting revisionist history entitled In the Shadow of the Monuments, taken from Richmond real estate ads of the late nineteenth century, and doing a segment with Anderson Cooper on 60 Minutes. Directly related to the fate of Richmond’s five grand monuments, Stoney, unsuccessful at removing Richmond’s monuments, recruited Landrieu for a large event at Richmond’s Museum of History and Culture on March 22, 2019. Efforts by Stoney and Councilman Michael Jones moved at a snail’s pace. It appeared that Richmond would not be joining New Orleans in purging their public spaces from those symbols of slavery and white supremacy. Scandals related to the founder of the SPLC and their offshore bank accounts, as well as their losing several large defamation suits, allowed the Richmond monuments to live another year. But when a black man died at the hands of police many miles away in Minneapolis on May 26, 2020, Richmond’s downtown became a battleground of violent protest. It took only four days until gunshots were heard, fires broke out and the five unprotected monuments were attacked with impunity. Knowing that the monuments were magnets for the mobs, Stoney did nothing to protect them. Governor Northam and the Virginia Assembly, likewise, removed all protection on June 4th by amending the long-standing state law thus eliminating arrest, fines and punishment for defacing or removing them. When the mob focused its hate on the great Lee monument, it was almost 130 years to the day of the monument’s grand dedication ceremonies. The events of the great unveiling of Richmond’s Lee monument appeared in the May 29, 1890 issue of the Alexandria Gazette. The monument, they reported had been years in its planning and construction. The base which was completely covered in graffiti 130 years later was made of James River and Maine granite at a cost of $42,000. In current terms that would be 1.1 million dollars. The bronze equestrian statue of Lee on his horse Traveller was created by Paris sculptor Charles Antonin Mercie, taking years of study. The horse alone took two years. Mercie was paid $18,000. The final cost, paid by thousands of individual contributions was $75,000, which today would be over 2 million dollars. The article in the Alexandria Gazette announced:

Newspapers of that time give an accurate picture of how each of Richmond’s monuments were financed, and their costs. They also reveal who then owned them. In 1928 for instance, the Richmond paper announced that the state had promised $10,000 toward the monument for Confederate naval officer Matthew Fontaine Maury. It announced the need to raise an additional $40,000. From private contributions. So, both the state and private individuals were vested in its making. The application for National Historic Landmark painstakingly includes mention of 358 historic and architecturally significant residences and churches starting with J.E.B. Stuart on the 1600 block and ending with the Arthur Ashe monument on the 3300 block of Monument Avenue. The documentation clearly shows the inter-relatedness of 358 buildings with the six monuments, with the monuments being both the reason for their being there and the glue that joins them together. You will find nothing that could compare in any other American city. At the beginning of the War for Southern Independence, Richmond and New Orleans were the Souths two largest cities. Unlike New Orleans, Richmond had to rebuild entirely after the war. In the years after the war, New Orleans competed with Richmond funding and erecting monuments to their heroes. But Richmond’s Monument Ave was much more than erecting monuments; it was urban renewal. Over the next several decades the neighborhoods and monuments were built together. This historically unique relationship became recognized and celebrated when in 1997, Monument Avenue became the first American street to become a National Historic Landmark. It is this distinction and national recognition that is the basis for a lawsuit to restore all of Monument Avenue’s monuments. Besides the cover sheet for the approved application, that indicates complex ownership of the buildings and monuments that make up the landmark, the very language and supporting documentation are impossible to ignore:

While I am not an attorney, It was very clear in 1997 that a department of the federal government, the National Parks Service and its appointed historical authorities not only acknowledged the inseparable nature of the properties but its importance of the sculptures honoring Confederate heroes. Stoney and the Richmond City Council violated 18 U.S. Code 1369 Destruction of Veterans Memorials, since the United States recognized Confederate soldiers as veterans early in the twentieth century and this national healing memorialized by the burial of Confederate soldiers in Arlington National Cemetery. This law comes into play because all the monuments were “under the jurisdiction of the federal government” when they became designated as national landmarks. The law reads:

When mayor of the city in the summer of 2020, the city had a population of 234,081 people. There were no public meetings and the mayor and council never got consensus from the residents and stakeholders. Using am ‘emergency” as a justification, they first refused to protect the valuable monuments from vandalism and arrest the criminals, but in only a week’s time, removed the statues from their pedestals.

American historians and political scientists know that the majority of Americans have moderate views. They occupy the political center. Likewise, then, the majority of 326.7 million Americans have no animosity toward the South or fearful thought of the South rising again. The majority of Americans appreciate the history and the heroic figures and places associated with that history. This makes Ralph Northam and Levar Stoney a very small minority and their views and beliefs extreme. A local contractor Devon Henry, who had contributed $4000 to Stoney’s political campaign, after no Virginia contractor would agree to the monument’s removal contracted a Connecticut company to remove the monuments. Unlike Landrieu’s private donor, this cost Richmond 1.8 million dollars. It was not till September 19, 2022 that any official called for an investigation into Stoney’s obvious pay to play with the monuments. Justice for the monuments calls for a substantial lawsuit that would challenge the actions of Stoney and the city on the basis of ownership of the monuments. As stated, the cost to make the Robert E. Lee Monument today would be in excess of 2 million-dollars. The other four: Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, Jeb Stuart and Matthew Fontaine Maury at 1.5 million each establishes the value and loss of 8 million-dollars. The Maury monument for instance, finished in 1929 cost $50,000. Today the same small monument would cost $867,860. While in the process of redevelopment, the city of Richmond, the state and the city gave up small portions of property for the creation and installation of monuments. The receipts for the sculptors and materials, as well as the contractors show clearly the monuments were privately owned. A fact not discussed at the time and now, two years later. Adding further insult to injury, Mayor Stoney announced on New Year’s Eve, 2021 that the city and state had made an agreement to convey ownership of the statuary from the monuments to the Black History and Culture Museum of Virginia. The Museum director promised that the former proud monuments would be used to tell a completely different narrative from the one intended by the true owners. Lee, Davis, Stuart, Jackson, and Maury would then be paraded as artifacts of a pro-slavery and white supremacist culture clinging to their Lost Cause. Meantime, the exceptional bronze artifacts, worth millions lie scattered on the grounds of Richmond’s water treatment facility. Because the entire district, mansions, homes and apartment buildings owed much of the value of their properties because they existed in the shadow of the monuments will now collectively lose value, an amount almost impossible to approximate. There will also be in the decades to come, a measurable decline in tourism dollars. And for what? So that a politician could virtue signal? Upon their speedy removal, a variety of people entertained ideas for monuments and memorials that could be put in the now empty parks. No one could agree. It turned out that no matter the individual be considered, all were not without sin and had reasons for disqualification. In terms of history, everyone being considered would leave Richmond with unreasonable and historically inauthentic markers. A prime example being the proposed creation of monuments to famous abolishionist in the city that was the Capital of the Confederacy. Stoney’s speedy removal violated all that was left of Virginia’s law. The Virginia assembly left the stipulation in the law that mandated a thirty-day notice by officials, so that the monuments might find another home and safety elsewhere. A small point, but a matter that is more evidence of the mayor’s recklessness. The Richmond police department has refused to respond to my Open Public Records Requests. I feel strongly that there exists proof that Stoney ordered the police to stand down as far as arresting individuals for defacing and damaging the five monuments. Afterall, after many nights of violence against the city and businesses, the only arrests were weeks later and to enforce a band against assembling. True Southerners should be grateful to the individuals who successfully brought about the designation of Monument Avenue as a National Historic Landmark. Using their federal protection under the law in a well-crafted lawsuit, the South and her monuments can get their well-deserved days in court. Only by seeking a favorable outcome can we return what was stolen to their rightful owners, the generations that will follow.

3 Comments

|

AuthorTed Ehmann was born in Trenton, New Jersey. He is a lecturer of the social sciences and the humanities at the PGICA.org. in Punta Gorda, Florida. He has served as president of the Charlotte Harbor Anthropological Society in Charlotte County since 2018 and was founder of the Charlotte County Florida Historical Society in 2019. Archives

January 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly