|

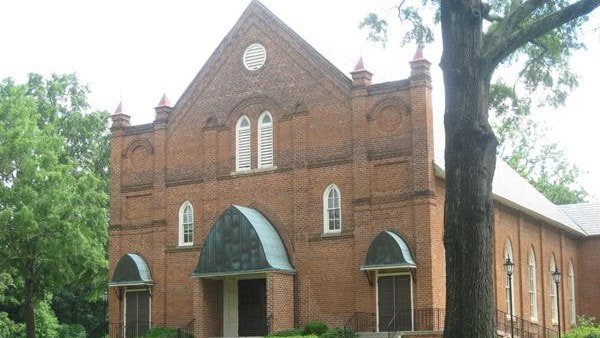

Early this past summer the historic Steele Creek Presbyterian Church, near the city of Charlotte, North Carolina, closed its doors for good. The church, the second oldest in Mecklenburg County, having been founded in 1760—nearly 259 years ago—by hardy Scots settlers to the region, merged with another Presbyterian Church in the area, Pleasant Hill. The classic 1889 Gothic-revival style brick structure was abandoned, purchased by nearby expanding Charlotte Douglas International Airport. As late as the early 1970s Steele Creek counted 1,000 members, but the encroaching airport and the constant deafening roar of supersonic jets every moment of the day speeding off to Munich, London, Latin America and all points in between, plus the precipitous decline in the Presbyterian Church USA, which has gone the way of all mainstream Protestant denominations and embraced the liberal social gospel, had brought the membership down to around 350, many of them adults who held on to the memory of a Presbyterianism that once boasted of a Reverend Robert Lewis Dabney…but now could only grasp for scraps from a barren progressivist table. Next to the historic 1889 building is the Steele Creek Cemetery, one of the more historic burial grounds in Piedmont North Carolina, holding over 1,700 graves, the earliest from 1763, twelve years before the onset of the Revolutionary War [See: The History of Steele Creek Presbyterian Church, 1745-1978; Third Edition, Charlotte, 1978] In that cemetery are laid veterans of every conflict and war that the American nation has engaged in: those who served during the Revolution when the then-tiny hamlet of Charlotte served as an unwelcoming “hornet’s nest” for General Lord Cornwallis; a few who went off later to fight in Mexico or against Britain again in the early Nineteenth Century; many more who joined Confederate ranks to defend the independence and rights of North Carolina in 1861-1865; then, others who fought in the great world wars and conflicts since then. But there are others, also: husbands and wives, and children, of those who had formed up until recently a close-knit, church-oriented farming community like many spread over the Tar Heel State and the South. Since 1777 over sixty members of my father’s family have been buried in Steele Creek’s sacred ground. Six of them are direct ancestors, including my grandfather and grandmother Cathey, my War Between the States great-grandfather, Henry Cathey (of the 13th North Carolina Regiment), and my eight-greats grandmother, Jean, who was born in County Monaghan, Ulster, in 1692, a descendant of Scots who migrated there from Ayrshire in the early 1600s. As a young boy I recall vividly attending the funeral of my grandfather, Charlton Graham Cathey (1958), in the old sanctuary and the impressive minister Reverend John McAlpine who comforted my grandmother who would pass on four years later in 1962, aged nearly 98. Those events remain engraved in my memory, even to the point of recalling the hymns sung at granddad’s funeral—“How Firm a Foundation” and “Blessed Assurance,” two of his favorites. But most of all, I remember that remarkable church, its strong and impressive brick structure, that aura associated with and radiated by it, which deeply connected it to the history of old Mecklenburg County, to North Carolina, and to the land and families who settled nearby, and for which it was the center of their lives for generations. The cemetery remains in church hands, despite the shrinking congregation having departed. It is too historic, so despite some earlier efforts by the airport authority to have the graves moved, it will remain where it is for the foreseeable future. But the old 1889 structure, its brick walls and interior now silent, is deserted, owned by the airport, serving only as a disappearing memory for those who care to recall what it once meant to so many. If we compare modern million-person Charlotte and its international airport to the history-haunted walls and ancient graveyard of Steele Creek, we are reminded of what has been lost. For in the bustle of the metropolis and the incessant noise of the jets zooming off to Europe or perhaps to Cancun, there is little memory of who we were as a people, little connection to our rich historic culture. Our modern society is hypnotized by machines, including the most impersonal and inhuman technology, and it has little room for Steele Creek and what it represents. In the late 1950s, Charlotte, “the Queen City” that I remember as a boy, was where older families yet predominated, where my father’s people were neighbors to the families of Billy Graham and Randolph Scott, where folks could recall the area’s history. Charlotte and Mecklenburg County were still linked strongly to their traditions. Now Charlotte rivals Atlanta as a mega-metropolis, and a soul-less anthill of business, banking and international commerce, with little room for heritage, except as a veneer to attract an occasional tourist not going to a Carolina Panthers game or to some big event at the coliseum. I forget who said it—perhaps Faulkner, maybe Louis Rubin, I cannot remember—but that if he had known what Atlanta would become today, then he would wish that Sherman had torched it more thoroughly. Given what Charlotte has become, perhaps the same sentiment might be expressed? The last major portions of farmland out near the Catawba River that had belonged to my dad’s family since 1750 are now sold to developers and strip malls. The pre-Revolutionary War house that my father was born in back in 1908 (the last of his family to do so) is now, thankfully, preserved at the Historic Latta Plantation. But the whole region has changed radically, altered and almost unrecognizable and discordant to my memories of sixty years ago. Hundreds of thousands of transplants (mainly from up North) now make Charlotte and its suburbs home and live—if you wish to call it that—the frenzied life of our tawdry, commercialized age. I am put in mind of the great Southern Regionalist writer, Donald Davidson, in his epic poem, “The Tall Men”:

There are remnants of the old culture that survive, a few, but they are fast being overtaken by a triumphant “Yankee” culture which Robert Lewis Dabney warned about 140 years ago, the fear that we would, as he said, become like our conquerors of 1865. Dabney, the Old Light Presbyterian divine that he was, declared that his role was like that of Cassandra at Troy, to prophesy and speak truth, but not to be believed until too late. My mentor Russell Kirk once told me while we were discussing the old South and the changes being inflicted on her from both without and within that “it is hard to love the gasoline station where the honeysuckle used to grow.” Steele Creek Church and its cemetery remind us who we are and who we have been. Despite being passed by and deserted, those grave stones cry out to those who would listen and take heed. Perhaps, then, for those who do, our watchword could be from Spanish philosopher, Miguel de Unamuno in his volume, The Tragic Sense of Life: “Our life is a hope which is continually converting itself into memory and memory in its turn begets hope.” Is this not, then, our challenge, to keep both memory and hope alive?

1 Comment

What the Historic South has to Teach America: Readings from Conservative Scholar Russell Kirk11/12/2019 Many present-day Southerners—indeed, many of those Americans who call themselves “conservatives”—find it difficult to envisage a time when Southern and Confederate traditions (not to mention noble Confederate veterans like “Stonewall” Jackson and Robert E. Lee) were acknowledged with honor and great respect. Today it would seem so-called “conservative media” (in particular Fox News and the radio talksters) and Republican politicians would rather praise “Father” Abraham Lincoln or the radical black Abolitionist, Frederick Douglass (whose extra-marital liaison with German-born socialist and feminist Ottilie Assing certainly influenced him and should raise eyebrows among contemporary conservatives, but seldom does). These and other revolutionary zealots have been incorporated into the pantheon of “great conservative minds,” dislodging such figures as Jefferson Davis, John C. Calhoun and John Randolph of Roanoke, all of whom possessed towering intellects and an acute understanding of the history and nature of the American republic which Lincoln, Douglass, and those like them lacked. It is far too common in 2019 to witness the historical ignorance of a Dinesh D’Souza or the meandering narration of a Brian Kilmeade in the godawful Fox series, “Legends & Lies: The Civil War,” in which he accuses the South of “attempting to rewrite history by denying slavery was the root cause of the Civil War,” and parrots the far Left template on racism. And what of distinguished Southern writers who defend the South like historians Drs. Clyde Wilson or Brion McClanahan? Or literary luminaries such as James E. Kibler? Or Emory University scholar Don Livingston? When was the last time you saw their byline in the current, Neoconservative-edited National Review, once the “conservative magazine of record” in the land? They are, to use a Stalinist metaphor, “non-persons” among establishment conservatives and the contemporary “conservative movement.” One must not, under any circumstance, mention their names among Neocon intelligentsia circles, lest suspicions of “racism” or “Neo-Confederate tendencies” be exposed. Perhaps the worst event symbolizing this exile was the unceremonious expulsion—the political defenestration—of arguably the South’s greatest essayist and author of the last quarter of the Twentieth Century, the late Mel Bradford. Tapped originally in 1981 to be President Ronald’s chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Bradford was a staunch defender of the original American Constitution, an acerbic and powerful critic of Lincoln and his legacy—and a defender of the South. According to chronicler David Gordon: "Bradford rejected Lincoln because he saw him as a revolutionary, intent on replacing the American Republic established by the Constitution with a centralized and leveling despotism." Although supported by such notable figures as Russell Kirk, Jeffrey Hart, Peter Stanlis, and Jesse Helms, Bradford was forced to experience an ugly, defamatory and underhanded campaign by the Neocons George Will, the Kristols pere et fils, and others to halt his nomination, in favor of Democrat Neocon, William Bennett. And, tasting blood, the new rulers of the conservative movement were successful. Yet, it was not always so. A half-century ago Southern writers of distinction, defenders of our traditions and heritage, including of our revered historical figures and champions of the Confederacy, were welcomed in national conservative publications like National Review. And in Russell Kirk’s scholarly quarterly Modern Age, that acknowledged “father of the conservative revival” of the earlier 1950s, dedicated an entire issue to the South and a defense of its traditions, including its Confederate history. Kirk had authored what became in a sense the “Bible” of that revival, The Conservative Mind (1953), and his words carried tremendous weight. That he would publish a whole issue celebrating the history and essential role of the South in America [Modern Age, Fall 1958], right on the cusp of the radical “civil rights” movement of the 1960s, almost in defiance of it, was a measure of the importance older conservatives attached to the Southland and their embrace of Southern traditionalists. In the prefatory essay to that issue, “Norms, Conventions and the South,” Kirk authored, as only he could, a stirring and profound defense of the traditional South, its virtues, and its critical significance in the survival of the American confederation. In it he declares that the South represents “Permanence”—the “permanent things,” the norms and conventions handed down for generations which moor and have stabilized the American Republic, and without which the country would be adrift and subject to demagoguery, decay and dissolution. But Kirk also—sixty-one years ago—had a warning and an admonition for Southerners: How much longer the South will fulfill this function, I do not venture to predict here. I am aware of all those powerful influences, material and intellectual, which are changing the South today. It may be that the South, in the end, will be made homogeneous with all the rest of the nation, and that its peculiar role as conservator of norm and convention will be terminated. But if this comes to pass, the South will have ceased to exist: it will have lost its genius. What would Kirk, “the Sage of Mecosta,” that superb word-smith and Olympian man-of-letters say today he if were to return to our Southland? What verdict would he cast on those guardians of our heritage and our inheritance…and the actions we and our fathers have taken, or not taken, during the past six decades? How would Kirk—who saw before he passed away in 1994 the poisonous infection of the Neoconservatives—evaluate the willingness of far too many Southern “conservatives” to forego serious investigation into and defense of their history and accept the “mess of stale porridge” offered up by a Brian Kilmeade, or a Dinesh D’Souza, or a Senator Lindsey Graham? In his essay Kirk employs the great Virginian John Randolph of Roanoke to bring home his message: …John Randolph is the most interesting man in American political history, his wisdom and eloquence curiously intertwined with vituperation, duels, brandy, agriculture, solitude, and tragedy. Through Calhoun, [Langdon] Cheves, and many others, Randolph’s opinions were stamped indelibly upon the South…. A fervent Christian, a champion of tradition, the principal American expounder of Burke’s conservative politics, Randolph of Roanoke abided by enduring standards in defiance of power, popularity, and the intellectual climate of opinion of his era. In his oratory in the U.S. Congress and his eloquent speeches to his constituents in Southside Virginia, Kirk continues, Randolph explained that, There are certain great principles…which we ignore only at our extreme peril; and if those principles are flouted long enough, private character and the social order sink beyond restoration. In this, as in much else, Randolph was the exemplar of the Southern society. For the South has long been the Permanence of the American nation. Strongly attached to Christian belief, bound up with the land and the agricultural interest, skeptical of the visions of Progress and human perfectibility, imbued with the tragic sense of life, the South has not been ashamed to defend convention and continuity in this great, swelling, confusing Republic: to abide by ancient norms of private and public life. The problem of the races informed Southerners that society’s tribulations are not susceptible of simple abstract remedy; the rural life kept the South aware of the vanity of human wishes, the existence of Providential purpose, and the immortal contract of eternal society; the political and literary traditions of the Southern states endured little altered by the nineteenth- and twentieth-century passion for innovation. Military valor, courtesy toward women, and the pieties of community, home, and family persisted in the South despite defeat and poverty and the intellectual ascendancy of the North. So it is that in our time of troubles the South has something to teach the modern world. And this recognition extended throughout Southern culture, and most especially in the richness and profundity of Southern literature: …Southern writers still recognize those enduring elements of human nature, including the splendor and tragedy of human existence that are the stuff of which great poetry and prose are made. Belief in normality, and defense of convention, have not lain like lead upon Southern thought and life; on the contrary, these have been the foundations of Southern achievement….In its taste for imaginative literature, similarly, the South has chosen for its favorite authors the champions of norm and convention…. [and] a spirit of courage, of chivalry, of loyalty, an expression of ancient truths, that was congenial to their instincts. For those on the Left, for those Dr. Kirk calls “doctrinaire liberals, the zealots for Progress and Uniformity,” the South continues to represent all of the worst and most hated aspects in American history: racism, slavery, misogyny, white supremacy, religious fundamentalism and bigotry. But, as Kirk explains, that hostility is rooted in a deeper prejudice that “the South still stands resolute in defense of norms and conventions. To the ritualistic liberal, the South is what [George] Santayana called ‘the voice of a forlorn and dispossessed orthodoxy,’ rudely breaking in upon the equalitarian dreams and terrestrial-paradise schemes.” It is the Left’s own form of poorly concealed bigotry. For the contemporary post-Marxist revolutionary Millennial, the fanatical indoctrinated student brandishing a “Black Lives Matter” placard, the loony feminist demanding an end to masculine oppression, and the LGBT zealot pushing transgenderism, the South and its traditions are major impediments to the realization of a dreamed of Utopia that is in reality a dystopian nightmare far worse than any vision ever entertained by Comrade Stalin or Chairman Mao. The convictions and customs of the South perpetually irritate the radical reformer, who is impatient to sweep away every obstacle to the coming of his standardized, regulated, mechanized, unified world, purged of faith, variety, and ancient longings. Permanence he cannot abide; and the South is Permanence. He hungers after a state like a tapioca-pudding, composed of so many identical globules of other-directed men….he flail[s] against the champions of norm and convention, endeavoring in the heat of his assault to forget the disquieting voice of a forlorn and dispossessed orthodoxy that prophesies disaster for men who would be as gods. And in one of those memorable passages for which Russell Kirk is remembered and celebrated, he closes his essay in striking form—a remarkable tribute to the traditional South, its heritage, and its pivotal role in the creation and sustaining of an America which seems to be passing away now before our eyes: My argument is this. Without an apprehension of norms, there is no living in society or out of it. Without sound conventions, the civil social order dissolves. Without the South to act as its Permanence, the American Republic would be perilously out of joint. And the South need feel no shame for its defense of beliefs that were not concocted yesterday. So, I repeat my question: What would that Northern champion of the South and its role of Permanence in our confederation say today? Can that South that Russell Kirk so lauded and defended survive, even in our dark times? And what is our obligation, our solemn obligation to our native land, to our ancestors, and to those who follow us? |

AuthorBoyd D. Cathey holds a doctorate in European history from the Catholic University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, where he was a Richard Weaver Fellow, and an MA in intellectual history from the University of Virginia (as a Jefferson Fellow). He was assistant to conservative author and philosopher the late Russell Kirk. In more recent years he served as State Registrar of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History. He has published in French, Spanish, and English, on historical subjects as well as classical music and opera. He is active in the Sons of Confederate Veterans and various historical, archival, and genealogical organizations. Archives

May 2024

|