|

My country is not a snow-capped mountain In the Colorado Rockies Or a seacoast town in Maine Or the tropical islands of Hawai’i. Fine places to be sure, With many fine folks, But they are not my country. My country is a little strip of land in Arkansas, Near where the wagon wheel fell off – The beginning of the Walton family homeplace there in Strong, Where our roots have burrowed deeply down, The source of our strength, unity, and identity. You belong to Gen X or Z? I belong to the Walton clan, Whose line we trace back through four centuries Of years on this continent, and beyond that Over yonder in the Old Country. You celebrate the birth of an abstraction Called America on July 4th? I celebrate the birth of an actual man, Raiford Randolph Walton, my grandfather, A leader in war and in peace, And a patriarch of his kin. You pride yourself on watching debates Between a pair of Tweedle-Dums? I would rather know about the pair of girls Growing in my cousin’s womb. My country is my family, Here with the big hearts And loving souls in little Strong, And wherever else they may be, In Dixie’s land, or further out beyond.

2 Comments

Louisiana’s Superintendent of Education Dr. Cade Brumley stirred up a bit of a tempest by recommending Prager U resources to Louisiana’s teachers as supplemental teaching material. Encouraging teachers to use material outside the monopolistic, Left-leaning textbook racket is a good idea, and should be expanded, but Prager U should come with some warning signs for those who care about the faithful presentation of history. The two Prager U videos about Frederick Douglass that Scott McKay included in his story about Dr. Brumley are good examples. The videos portray Mr. Douglass as a peace-loving, non-violent abolitionist content with incremental efforts to end slavery within the established constitutional system. More specifically, they imply that he is the opposite of folks like the George Floyd protesters, who sated themselves with murder, arson, and looting in 2020. This is not historically accurate. Mr. Douglass’s speech on 3 December 1860 in honor of John Brown is a case-in-point. John Brown was one of the vilest Yankees (may God have mercy on his soul), determined to stir up a murderous slave revolt in the South. He gave it his best shot at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, a venture planned and funded by some of the most wealthy and influential men of the North (the Secret Six), but it failed:

One would expect Mr. Douglass, if he were the sort of man shown in the Prager U videos, to have denounced this heinous act, but he did the opposite. Here are his own words from 1860 praising John Brown and encouraging acts of violence and terror against Southerners:

And if Christianity still means anything to conservatives in the States, they might also want to know that Mr. Douglass venerated two rather questionable German thinkers – Ludwig Feuerbach and David Strauss (busts of them rested on his fireplace mantle), both of whom were intent on remaking Christianity to conform to skeptical, humanistic Modernity. This isn’t the first time that Prager U has been dishonest about the past. They have posted videos about slavery and its role in the misnamed Civil War and about Reconstruction that have also told some exceptionally grand whoppers. For those who might think all this fussing about the past doesn’t amount to very much, they need to think again. There is a direct line from Northern abolitionist thinking to modern insanities like homosexual marriage and trans rights. Neil Kumar gets the ball rolling:

We see this exact same twisting of Christianity in President Biden’s 2024 Pride Month Proclamation:

God is not the author of sinful behavior, nor does He call upon us to support it, but the progressives today, like their radical abolitionist forefathers, continue to try to reshape Christianity to fit their beliefs. Given the slippery, downward slope of Christian revisionism the Northern abolitionists have placed folks in the US upon, how should one view slavery to avoid those false teachings and their woke offspring? To answer that, let’s look at El Salvador. The situation President Bukele inherited was atrocious: The murder rate, driven by gang violence, was at an unbelievably high level (one murder per hour by 2015). Bukele’s answer was a forceful crackdown, mainly through mass incarceration of gang members:

What Bukele was facing with regard to gang violence was essentially what folks in the colonies (mostly in Dixie) were facing with an influx of pagan Africans: trying to find the best way to deal with a bad situation. The answers in both cases were similar: restrictions of freedoms until the gangs and until the Africans showed they were capable of exercising freedom in a responsible way (this is also why most teenagers can’t vote, and why children are under obedience to their parents). That chafes ‘secular Enlightenment sensitivities,’ but for traditional Christians it makes sense, for they understand that sin must be restrained, or individuals and society as a whole will suffer temporal and eternal harm. No less a Church authority than St. Augustine of Hippo (+430) writes in The City of God,

Put another way, as long as there is sin, then slavery, whether in the form of Bukele’s massive prisons or the much milder Southern form of paternalistic bondage, may be needed to deal with it. One of the South’s own notable Christian philosophers, Reverend Robert Lewis Dabney (reposed in 1898), says this in his usual inimitable way in his A Defence of Virginia and the South (p. 259):

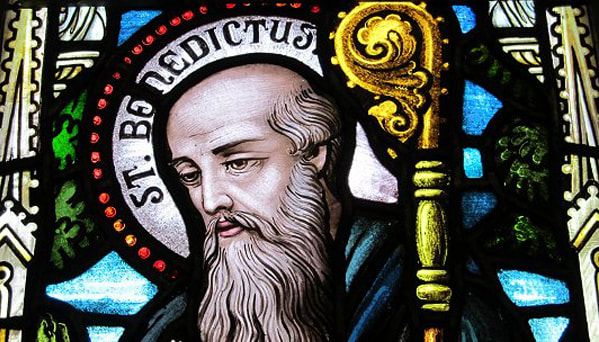

Prager U has a problem. Some of its content is informed by the same heretical, man-worshipping Enlightenment spirit that drove Northern abolitionists to support horrific acts of violence against Southerners and that still drives harmful ideologies like transgenderism today. Folks in the States are growing rather desperate to see better times. If they follow the Enlightenment path, they will not find it. Only by rejecting idols and yielding to Christ will those times come, the same Christ who is able to take even lowly slaves and raise them up into the highest echelons of the Heavenly Kingdom. It is written of St. Blandina (+177), one of the illustrious Martyrs of Vienne in France,

St. John (+1730), a Christian soldier captured by Turkish Muslims and made their slave, is another powerful example of a slave attaining the highest level of achievement for a man or woman – holiness, sainthood.

Sin is the greatest problem afflicting mankind, not slavery. The latter is the result of the former. If we eradicate sin, we will necessarily eradicate slavery. Freedom in Christ is therefore the truest and best form of abolition available to mankind. That is the message that Prager U, Dr. Brumley, and all conservatives ought to be spreading, not a presentation of a Frederick Douglass who never existed nor utopian Enlightenment democratic theories. Sowing these latter will only cause us to reap in tears and lamentations another harvest of virulent social justice ideologies and their fervent adherents. [U]S foreign relations continue to be a dumpster fire around the world, which is causing many countries to rethink their ties with the DC FedGov. This should be both a rebuke and spur for the South – a rebuke, for most of our people seem content to remain united to the DC ‘sewer,’ as Dr. Wilson put it recently; a spur, to separate from that corrupt capital. Niger, a country in north-central Africa (capital city – Niamey), is one of the latest to tell the Yankee Empire to hit the road. Prime Minister Zeine’s discussion of why they have done so reveals typical Yankee smugness at work:

The threats didn’t sit well with the Nigeriens, who responded with a mixture of politeness and frankness that any Southerner would approve of:

And, echoing the Declaration of Independence, he denounces the Empire’s quartering of troops in Niger while at the same time allowing lawless men to run about without hindrance:

The decrepit French Empire also faced reprisals from Niger for its meddling in Nigerien affairs:

These experiences have resulted in Niger looking to new countries for assistance:

Here at the South, we are experiencing the very same problems from an aggressive, arrogant, Yankee-dominated DC that Niger has, but our response thus far hasn’t been nearly as forceful as Niger’s. The federal government wants to dictate to the Southern States on things ranging from what cars we can drive to transgender rights in public schools to the maps of our congressional districts, while they fail in one of the most basic governmental functions (public safety) by allowing millions of illegal immigrants to flood into the States. Where is our will to counter these threats and survive as a Christian people?

There are some glimmers of hope, as Gov Abbott and the Texas Legislature have made some moves to secure their State’s border, while other Southern States have bluntly said they will not comply with the Biden regime’s transgender rewrite of Title IX and have initiated some lawfare over it. Still, the main problem is spiritual: Too many Southerners remain under the spell of the notion of a mystical, unbreakable union of the States and the exceptionalism of this union in world history. Until we reject these false ideas, unite around the Christian Faith and our Southern patrimony, and seek out Christian and traditionalist allies in the world, we will continue to suffocate beneath Yankee/globalist culture and politics. The actions of Niger ought to inspire Southrons: It is possible to break free from the tentacles of DC. And having done so, should the Lord allow it, may our love for our Southland never wane again as it has so lamentably over the last several decades but remain fervent forever. Even before the colonies separated from Great Britain in 1776, the South has had an adversarial relationship with the Yankees of the north, who, because of their arrogance, have demeaned Southern culture and forcefully tried to transform Southrons into Yankees. Southerners tried to put an end to that in 1861 but were unsuccessful, which resulted in even greater domination of the South by Yankees and their ideas over us these last 159 years. Motivating Southerners to throw off the Yankee yoke is difficult because of this: Yankee ways are so ingrained, Yankee power is so strong (through the federal government bureaucracy, media of various sorts, and giant corporations), that few desire to challenge it, even if it means the complete annihilation of Southern culture. It is at this point of despair that Dixie can gain a good measure of hope from her African cousins in Senegal. Like Dixie, she has long been dominated by the equally boastful (equal to the Yankees, that is) French elite, who established a presence in Senegal in the 17th century. Even after her independence in 1960, French influence continued to overshadow her. But the presidential election in Senegal this past March has upended the status quo, as evidenced by the response of the upper French classes:

The quote at the end equally applies to the Yankee-Southron relationship: ‘If a Dixian is praised by a Yankee, you can be certain he is betraying his people; but if a Yankee criticizes a Dixian, this latter fellow is doing something good for the South.’ The author of the article goes on to say,

The Yankee Empire, like the French Empire, is diminishing in the world, thanks to evil actions of its own as well as to wise and prudent actions of other countries like Russia, China, India, Iran, and others. The South, thus far, has not contributed in any large measure to that decline. Yet it would be to the glory of the Southern people if someday someone would write of us that ‘Yankee imperialism found its grave in Dixie.’ But in order to reach such a decisive stage of development, the South will need to achieve what Senegal has of late:

Pride in Southern culture, an economy that benefits Southerners and not Yankee exploiters and usurers, cultural and political independence from Yankees – we have a long way to go, but if little Senegal can find the wherewithal to do this, cannot we at the South succeed also, we who have many more resources at our disposal to resist and depose the Yankee oppressors than the Senegalese have against the French?

It would truly be shameful for the Muslims to, yet again, outshine the Christians in their duty to oust foreigners who trample upon their long-held and sacred traditions. From parents in Dearborn, Michigan, to Taliban soldiers in Afghanistan, to Senegalese voters and their new president, Muslims around the world have been doing just that. May God rouse us here at the South from our apathy so that we will defend the better tradition, the Christian tradition, of our ancestors against the Yankee vandals.

Romanticize nature all you like; Rhapsodize about her many delights. But when the copperhead appears in the yard, And cold fear creeps in and grips your heart, Then you will know in your inmost parts That Adam’s Fall is no superstitious lie. The increasingly technocratic, anti-Christian trajectory of the West and other parts of the world is making traditional family life difficult to begin and sustain. This includes things like the LGBT cult, but also newer evils that go beyond them. Here are a few recent examples to illustrate: Treating pregnancy as a diseaseThe Journal of Medical Ethics, like a demonic oracle, opines:

Of course, this sick reasoning rests upon the un-Christian theory of Darwinian evolution:

Creating synthetic human embryos and growing them in mechanical wombsResearchers have succeeded in creating synthetic embryos for the first time, without stopping to first answer the question of if they should be created at all. The embryos exist without the need for egg, sperm or sexual reproduction of any kind. They were engineered from stem cells and provide a window into the earliest days of human development.1 The scientists behind the synthetic embryos, including Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz, of the University of Cambridge and the California Institute of Technology, hope to study this so-called "black box" development period, as researchers are only legally allowed to grow human embryos up to 14 days.2 . . . While it’s currently against the law to attempt to implant a synthetic embryo into a human womb, the science is rapidly outpacing related regulations. "If the whole intention is that these models are very much like normal embryos, then in a way they should be treated the same," Lovell-Badge told The Guardian. "Currently in legislation they’re not. People are worried about this." In animal studies, synthetic embryos implanted into mice wombs did not survive. Similarly, when synthetic monkey embryos were implanted into monkey wombs, pregnancies were induced, although the embryos spontaneously stopped developing after a few days. However, if the synthetic embryos could one day grow into adults, we’d be entering into uncharted legal and ethical territory. Ethicist J. Benjamin Hurlbut of Arizona State University told Science that synthetic embryos represent "a matter of significant moral discussion and of significant moral concern." Scientists are already working on how to grow life outside of a human womb and, in 2021, Hanna and colleagues grew a mouse embryo in a mechanical womb for about half of a typical gestational term — a time period equal to a human embryo at 5 weeks. Growing mouse embryos "ex utero," the researchers said, is a valuable tool to investigate embryonic development in detail, but it comes with serious ethical questions, including might humans be next? The answer is yes, as Hanna told MIT Technology Review, "This sets the stage for other species. I hope that it will allow scientists to grow human embryos until week five." Are we headed for an "era of motherless births," in which babies are grown in laboratories via artificial wombs? It does seem to be where the research is rapidly headed. . . . According to the Genetic Literacy Project:

If anyone thinks this is just sci-fi fantasy, think again. A member of Sweden’s parliament proposed at the end of 2023 that research be done on artificial wombs so that women would be freed of the ‘burden’ of carrying their unborn babies. Women admit to preferring relationships with AI chatbots over those with actual flesh-and-blood men

All of the above are guaranteed to destroy strong, healthy families and high birthrates; they will not remain isolated cases either but will try to insinuate themselves into the everyday life of the united States (our beloved Southland not excepted). These are certainly evil days. The monks of Grigoriou Monastery on the Holy Mountain (Mt Athos) captured the essence of our times in their denunciation of the Greek parliament, which, under heavy pressure from the Biden administration, redefined marriage to include same-sex couples:

And yet they counsel us not to despair:

The Church must continue to speak out like this, boldly yet compassionately, like the prophets of old, as often as possible, to bring society back to sanity vis-à-vis the family. The Orthodox bishops of Greece published a letter on the Christian family that serves as an excellent example of what could be presented to our neighbors. The following is a central part of it:

Governments must do their part as well. The US federal government is currently too paralyzed and/or too Leftist to do much of anything good, but State and local governments can still act decisively. They can stop pushing the theory of evolution on school children, limit AI and social media use among minors, and outlaw synthetic human embryo research. The Alabama Supreme Court has taken a very positive step in this direction by ruling that all frozen embryos created for IVF purposes are human children subject to the protection of all laws. Southerners may rightfully take pride that this ruling came from one of their own States.

But governments need to go further. They need to codify via resolutions, laws, and amendments, the teachings of the Church outlined above regarding the family. The structure of the tax code and other laws and regulations must be rewritten to give preference to families, especially those with lots of kids, rather than to atomized individuals. Nullification of Obergefell v Hodges is also essential. The technocratic assault on the family must be faced manfully. Special sessions have been called in Texas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and other States to deal with issues like tax rates, redistricting, and crime. Those are worthwhile issues to discuss, but they pale in comparison to strengthening the family. Governors and legislatures ought to adjust their schedules accordingly. It is not very often that we would say something good came of the Super Bowl, but this year is a little different thanks to the dustup over the response (or lack thereof) to the Black National Anthem: ‘White Tennessee Democrat Congressman Steve Cohen was incensed that Super Bowl fans did not stand in respect for what he called the “Negro National Anthem” during Sunday night’s big game.’ Those who disagree with Rep. Cohen have generally stuck to some form of the argument that because the United States is one nation, it should and does have only one national anthem. It is precisely here that a helpful opportunity presents itself, an opportunity to remind one and all that the United States are not one country, but many countries. This may be done via two ways. First, politically. Fifty States make up the federation called the United States. Each one is a sovereign, independent country. This truth has been expressed since the earliest days of their independence from the British Empire. One important example: The Treaty of Paris of 1783, which ended the war between Great Britain and the States, says explicitly that each State is a nation in her own right: ‘His Brittanic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz., New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, to be free sovereign and Independent States; that he treats with them as such . . . .’ It has generally been the authoritarian centralizers in the US who have tried to spin out a different version of reality – that the 50 States are one country – folks like Alexander Hamilton and Justice Joseph Story. Abraham Lincoln took their theory and put into practice by force of arms in an illegal, unjust war, but delusions will last only so long before falling apart. The Soviet Union affirms that: Fifteen very different countries forcefully united under the rule of Godless communists in Moscow broke apart in 1991. The European Union is constantly in danger of falling apart because it is similarly trying to amalgamate 27 independent countries into one giant supernation; Charlemagne’s earlier version of a European superstate fell apart for similar reasons. The United States are not immune from these political dynamics. Dissatisfaction with an all-powerful government in DC continues to manifest in the States. Texas’s de facto nullification of the Biden administration’s and the federal Supreme Court’s immigration directives is just the latest example. It appears that it will be only a matter of time before one or more States leave the present union. There is a second, and more fundamental, way that the United States are many countries rather than one: culturally. The easiest way to illustrate this is the Red State/Blue State dichotomy. In this regard, there are at least two countries existing within the current boundaries of the US – the conservative-leaning Red States and the liberal-leaning Blue States. But there is more to it than that. Because of the immigration patterns that have occurred in North America, there are several distinct cultural regions that have formed within the US. Speaking very generally about them, New England, because of her settlement by the people of southeast England, shares their penchant for cities and industry, and for egalitarianism and radicalism in politics and religion. Dixie, settled by folks from southwest England, is the opposite, favoring agricultural pursuits, rural lands, and hierarchy and tradition in politics and religion. On we could go: The Great Plains are more Scandinavian and German; the Rocky Mountain States are heavily Mormon; the Desert Southwest has a lot of Spanish influence; etc. All of this is well-attested to by authors such as David Fischer, Joel Garreau, and Colin Woodard. Religion, bloodlines/heredity, language, geography, and climate all combine to form unique cultures and countries that deserve as much autonomy as is possible within reasonable limits. Many in the US deny these very plain and simple truths, however, thinking that allegiance to a political creed is enough to empty people of their historical and cultural memories and roots and create new, blank-slate men and women who will inhabit a utopia called America. That didn’t work with the overly collectivist, individual-erasing communist ideology in the Soviet Union (the direction the EU seems to be going as well); it won’t work with the overly individualistic, community-erasing liberty ideology of the US either. Both are simply secular substitutes for the Christian Church – the only Body in the world capable of creating a new united race of men through the regeneration of the Holy Spirit. Because of this, we get second-rate ‘national’ rituals like the Super Bowl to help foster our unity rather than major feast days of the Church for the Lord Jesus Christ, His Most Pure Mother, other major saints, and so forth (to see what the South could be celebrating throughout the year, look here, here, and here). The healthier path for the States will be to recognize and nurture the various cultures amongst them, to allow them to coalesce into new confederations along rational regional/cultural lines, thereby putting to an end a lot of unnecessary clashes between States and cultures that hold opposing views on incendiary issues like abortion, drug legalization, transgenderism, immigration, marriage, guns, and the rest. Tell us again of the birth of God, When the sun was dying And humanity old and frail. Tell of the strong Deliverer, Who broke the chains around our necks, And the compassionate Healer, Who removed the iron lances from our hearts, Placed there by the murderous tyrant. Tell us of the young Maiden, The Mother of God, who knew no man, Whose womb became more spacious than the skies. Tell us of the new stars in the heavens, The new gods and goddesses – the martyrs and the saints – Replacing the old constellations of the pagans, Andrameda, Perseus, Hercules, With those reborn and recreated in Christ, St. Katherine, St. Paisius, the Great Basil. Tell us again of the deep, dark night When the Omnipotent was born as a helpless child, And hosts of the bodiless powers appeared, Singing praises while beholding a mystery. Tell us of the brilliant Light That erupted within hell, Crushing its bars and blinding its guards, And leading the captives home to heaven. Tell us again, and once more, and yet again Of the Love that united Godhead with manhood forever, That slew death like a viper struck with a sword, That will seat us next to Christ at table In Paradise, without fear of ever being cast away; Instead, deepening our union with Him As years and ages and aeons unfold In that world not made by human hands, Where together God, men, and angels will always abide. A woman is a mysterious thing, Whose simple, single ‘How’s it goin’?’ Is enough to befuddle a man, To frustrate his focus, To weaken his strength. The women who want to exercise Maximum power in the world By putting on a pair of pants And sitting on a corporate board Or in a senator’s chair Have got it all quite wrong – All they need do Is grab the men-folk rulers By their collars And tell them softly, ‘I love you so!’ |

AuthorWalt Garlington is a chemical engineer turned writer (and, when able, a planter). He makes his home in Louisiana and is editor of the 'Confiteri: A Southern Perspective' web site. Archives

July 2024

|