|

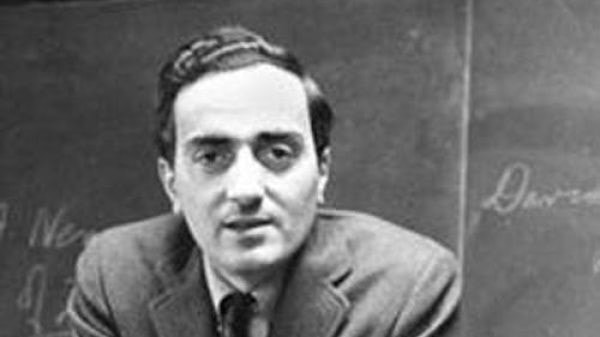

From late 1983 until its fitful demise in the early 2000s, I served as a contributing editor, adviser, or just simply a contributor to the old Southern Partisan magazine. Although a last issue came out in 2009, the quarterly had pretty much ceased regular publication a few years before that, largely due to internecine South Carolina politics and personalities. The valiant efforts of former Sons of Confederate Veterans Commander-in-Chief Chris Sullivan, as editor, to keep it alive were, alas, to no avail. Yet during its nearly three decades of existence the Southern Partisan published some of the finest writing about the South, Southern history, and Southern culture since the Agrarians of Nashville back prior to World War II. Begun originally in 1979 under the aegis of Thomas Fleming and Clyde Wilson, it featured in its pages essays by such luminaries as Mel Bradford, Cleanth Brooks, Eugene Genovese (not a Southerner, but an internationally-recognized historian who developed a sympathetic fascination about the South), Tom Landess, Russell Kirk, Reid Buckley (brother of William), Andrew Lytle, Don Livingston, and many others. I was privileged and very fortunate to be associated with those giants in a small way; over the years I had around fifteen essays and reviews published by the Partisan on subjects that have continued to interest and fascinate me: historical Southern figures such as Nathaniel Macon and Robert Lewis Dabney, several reviews of books by the late Dr. Russell Kirk (for whom I had served as assistant back in the early 1970s), an appreciation of the Southern-born actor and star of Westerns Randolph Scott, and lastly, reviews of books of Patrick Buchanan (a larger-than-life political figure with deep roots in the Old South and with a rambunctious mixture of Confederate and Irish Catholic ancestry!). There’s an old maxim that states “you’re known by the enemies you have”; and the Partisan had its share…and for many of us associated with it, that indicated we were having some effect. For much of its existence, it was a veritable bete noire for Morris Dees and his radical Leftist Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). In addition to seeing Klansmen under the bed of every “conservative” Southern politician and ferreting out every stench of Southern “racism,” the SPLC simply went apoplectic when the topic of the Partisan came up. They termed it “arguably the most important neo-Confederate periodical”, and thus the most dangerous to their fanatical totalitarian Marxist social justice agenda. The views it reflected were reactionary and anchored in a hateful past, not worthy of serious consideration in modern America. But the Southern Partisan could not be dismissed so cavalierly. Even The New York Times, the national journalistic flagship for frenzied and inflamed Progressivism, while denouncing the magazine “as one of region’s most right-wing magazines,” also begrudgingly admitted that "Many of [its] articles, however, are more high-minded historical reviews in the tradition of the Southern agrarian movement, which glorified the South's slow-paced traditions of farms and small towns." Although the Southern Partisan ceased to exist a decade ago, other voices have arisen to fill that void, most notably The Abbeville Institute, its superb summer schools and seminars, and its online review and blog. Clyde Wilson’s daughter Anne has also established a fine site, Reckonin.com, and it offers excellent commentary and reviews. And there are other venues where good writing and essays from a traditional Southern viewpoint appear. In 1985 I had the opportunity to interview the late historian Eugene Genovese for the Partisan (Fall 1985, volume V, no. 4), and it was the beginning of a close friendship that lasted until his untimely death in 2012. And it was a friendship that forever influenced me and my conception of Southern history and culture. For, beginning as a Vietcong supporter back in the 1960s, through a long and at times difficult evolution into the 1980s, Genovese had subjected the history of the South, the issue of slavery, and the “Southern mind” to the most severe and close examination. And, after it all, he became a stouthearted and brilliant defender of the South and its traditions (his friendship with the late Mel Bradford had undoubtedly assisted in that process). For Genovese the key to Southern history had been and was its firm foundation in traditional Christianity. It was a form of mostly Calvinist Protestantism, but also in a wider sense which warmly incorporated Catholics and Jews in its midst, but united in an broad consensus on the idea of a Christian society, which he found best expressed in the writings of the brilliant South Carolina Presbyterian theologian, James Henley Thornwell (d. 1862). Here he is in a passage on the South Carolinian, demonstrating a view that found resonance throughout the South: Shortly before his death Thornwell…in a “Sermon on National Sins,” preached on the eve of the War, and boldly in a remarkable paper on “Relation of the State to Christ,” prepared for the Presbyterian Church as a memorial to be sent to the Confederate Congress, he called upon the South to dedicate itself to Christ. He criticized the American Founding Fathers for having forgotten God and for having opened the Republic to the will of the majority. “A foundation was thus laid for the worst of all possible forms of government—a democratic absolutism.” To the extent that the state is a moral person, he insisted, “it must needs be under moral obligation, and moral obligation without reference to a superior will is a flat contradiction in terms.” Thornwell demanded that the new Constitution be amended to declare the Confederacy in submission to Jesus, for “to Jesus Christ all power in heaven and earth is committed.” Vague recognition of God would not do. The state must recognize the God of the Bible—the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. After the war—after Southern military defeat and the destruction of much of Southern society and eventually its culture—Thornwell’s clarion calls were picked up by another Presbyterian divine, Robert Lewis Dabney, who turned his Biblical ire and critical (and prophetic) intellect to the developing “Yankee empire,” religious indifferentism, and to the triumph of globalist capitalism and an imperialist and plutocratic “democratic despotism” (something that the Northern writer Henry Adams, scion of the Adams of New England, also recognized). In his magnum opus, The Mind of the Master Class (2005), co-authored with his wife Professor Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Eugene Genovese offered the finest and fullest—certainly the most documented—account and evaluation of a “Southern mind and intellect” that had conserved and illuminated the original, but oh-so-fragile vision of the Framers of the Constitution. Despite, or perhaps because of his earlier interest in Marxist theory, Genovese came to understand well, better than almost all his contemporaries, the extreme dangers inherent in post-War Between the States America. And that was why my interview with him nearly thirty-five years ago was so eye-opening. (The full lengthy interview published in the Southern Partisan is now reprinted in my recently published book, The Land We Love: The South and Its Heritage [2018], chapter 29: “A Partisan Conversation: Interview with Eugene Genovese.”) I quote below some extensive passages from that interview. Eugene Genovese and the Southern Partisan were incredibly productive and profound in their contribution to the defense, survival, and, even just maybe the reflorescence of Southern heritage. In our perilous times, when our traditions and heritage often seem hanging on by a mere thread, we can do no better than refer to their sturdy intellectual armament. Here is Genovese from 1985:

This piece was previously published on My Corner on September 8, 2019.

1 Comment

joe johnson

9/17/2019 11:51:55 am

I Know this is off topic, but has anyone read the piece over at the imaginative conservative website in honor of Martin Luther King, jr.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorBoyd D. Cathey holds a doctorate in European history from the Catholic University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, where he was a Richard Weaver Fellow, and an MA in intellectual history from the University of Virginia (as a Jefferson Fellow). He was assistant to conservative author and philosopher the late Russell Kirk. In more recent years he served as State Registrar of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History. He has published in French, Spanish, and English, on historical subjects as well as classical music and opera. He is active in the Sons of Confederate Veterans and various historical, archival, and genealogical organizations. Archives

May 2024

|