|

When it rains, it pours. After Charleston was put to the sword, all of its wealth was plundered and expropriated, its citizens imprisoned or impressed into British regiments throughout the far-flung Empire; as Simms described the degradation, “Nothing was forborne, in the shape of pitiless and pitiful persecution, to break the spirits, subdue the strength, and mock and mortify the hopes, alike, of citizen and captive.” At the Battle of Waxhaws near Lancaster, less a battle and more a massacre, Colonel Abraham Buford and his force of Virginian Continentals were mercilessly slaughtered while attempting to surrender by the dastardly villain, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, and his brood of Loyalists. After this wholesale butchery, “Tarleton’s Quarters”, that is, no quarter whatsoever, became an embittering rallying cry for the Patriots. Following so closely behind the sack and occupation of Charleston, the defeat of Buford, along with the only regular force of Continentals remaining in the State, crippled the hopes of the Patriots. As Simms continued, “The country seemed everywhere subdued. An unnatural and painful apathy dispirited opposition. The presence of a British force, sufficient to overawe the neighborhood…and the awakened activity of the Tories in all quarters, no longer restrained…seemed to settle the question of supremacy. There was not only no head against the enemy, but the State, on a sudden, appeared to have been deprived of all her distinguished men.” Moultrie languished in prison, while Governor Rutledge, Thomas Sumter, Peter Horry, and thousands of other Patriots withdrew to North Carolina and the other Northern colonies to join the Patriot cause there. Marion, meanwhile, still incapacitated, “was compelled to take refuge in the swamp and forest” as a fugitive, constantly on the lam. Still recovering, Marion embarked upon the road to North Carolina to join with a Continental force under Baron de Kalb, later superseded by the pompous Major General Horatio Gates. On his journey, Marion encountered Horry, who lamented that their “happy days were all gone.” Marion, stout-hearted as ever, replied, “Our happy days all gone, indeed! On the contrary, they are yet to come. The victory is still sure. The enemy, it is true, have all the trumps, and if they had but the spirit to play a generous game, they would certainly ruin us. But they have no idea of that game. They will treat the people cruelly, and that one thing will ruin them and save the country.” Gates’ Continentals ridiculed and sneered at Marion’s motley band of irregular partisans. Luckily for Marion, and very unfortunately for Gates, our hero was summoned to command the Whigs of Williamsburg, and thus determined to penetrate into South Carolina. In Marion’s absence, Gates led the Continentals to ruin. At the Battle of Camden, the site of which today is a nice pine stand right off of my favorite country lane, Flat Rock Road, the Americans suffered a devastating rout. Under Gates’ command, the Continental Army suffered its greatest loss of the entire War, thus precipitating that failure’s replacement with Major General Nathanael Greene. Marion, Simms noted, “was one of the few Captains of American militia that never suffered himself to be taken napping.” Just as Marion had predicted, British General Henry Clinton treated the people despicably. First, Clinton had issued a proclamation proffering “pardon to the inhabitants”, with few exceptions, “for their past treasonable offenses, and a reinstatement in their rights and immunities heretofore enjoyed, exempt from taxation, except by their own legislature.” Simms wrote that “the specious offer…indicated a degree of magnanimity, which in the case of those thousands in every such contest, who love repose better than virtue, was everywhere calculated to disarm the inhabitants. To many indeed it seemed to promise…security from further injury, protection against the Tories who were using the authority of the British for their own purposes of plunder and revenge, a respite from their calamities, and a restoration of all their rights.” However, snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, Clinton reversed course twenty days later and thereby galvanized the Southern Patriots. His second proclamation, Simms explained, required the people of Carolina to “take up arms for His Majesty, and against their countrymen…a hopeful plan by which to fill the British regiments, to save further importations of Hessians, further cost of mercenaries, and, as in the case of the Aborigines, to employ the Anglo-American race against one another. The Loyalists of the South were to be used against the patriots of the North, as the Loyalists of the latter region had been employed to put down the liberties of the former.” Promoted to General, Francis Marion took command of the country, donning a leather cap emblazoned with a silver crescent, inscribed with, “Liberty or Death!” Marion was simple, modest, taciturn, a man who taught by example rather than oratory, who “secured the fidelity of his men by carrying them bravely into action, and bringing them honorably out of it.” His watchword was activity, his anathema indolence. His first order of business upon assuming command was to supply some desperately needed provisions for his men. The first effort made on this front was to sack the sawmills, where “the saws were wrought and hammered by rude blacksmiths into some resemblance to sabers.” Thus provided, Marion set his men into action, launching a series of perfectly-orchestrated ambush attacks on Loyalist partisans, striking hard and then melting away into the backwoods as quickly as they had appeared. In an all too familiar refrain for Southrons past, present, and future, Marion was badly-equipped, often entering engagements “with less than three rounds to a man — half of his men were sometimes lookers-on because of the lack of arms and ammunition — waiting to see the fall of friends or enemies, in order to obtain the necessary means of taking part in the affair. Buckshot easily satisfied soldiers, who not unfrequently advanced to the combat with nothing but swan-shot in their fowling-pieces.” We must remember that Marion’s band of partisans was the only body of American troops in the State of South Carolina that dared openly oppose the triumphal ascendance of the British. Simms elaborated that “the Continentals were dispersed or captured; the Virginia and North Carolina militia scattered to the four winds; Sumter’s legion cut up by Tarleton, and he himself a fugitive, fearless and active still, but as yet seeking, rather than commanding, a force.” At Nelson’s Ferry, Marion’s scouts alerted him to a British guard detachment approaching their position, with a large cohort of American prisoners from Gates’ disaster in Camden in tow. Near the pass of Horse Creek, Marion ambushed them and freed all 150 Continentals, of which only three could be bothered to join him. Simms, somewhat sardonically, noted that “it may be that they were somewhat loth to be led, even though it were to victory, by the man whose ludicrous equipment and followers, but a few weeks before, had only provoked their merriment.” Earl Charles Cornwallis, falsely portrayed nowadays as a saintly gentleman, enforced severe and ruthless punishment for any Patriots or Patriot sympathizers, including the expropriation of all of their worldly belongings. Amidst widespread British and Tory atrocities, Marion ran the Enemy ragged, cutting supply and communication lines while denying the darkness any sense of security. Marion was so successful that Cornwallis sent Tarleton on an ultimately futile search and destroy mission to assassinate the Carolinian. Marion, as all great leaders do, loved his men dearly. His force was in constant flux, as his men, citizen soldiers, “had cares other than those of their country’s liberties. Young and tender families were to be provided for and guarded in the thickets where they found shelter. These were often threatened in the absence of their protectors by marauding bands of Tories, who watched the moment of [their] departure…to rise upon the weak, and rob and harass the unprotected.” If at all practicable, Marion granted all requests for leave; the loyalty of his men was such that their return was certain. Eventually, Marion’s band of backwoods freedom fighters was forced to temporarily retreat in the face of Tarleton’s contingents of Tories; it was with incredible reluctance that they left their communities unprotected, completely exposed to the vindictive cruelties of the British and their Tory lapdogs, “which had written their chronicles in blood and flame, wherever their footsteps had gone before.” Bitter though this was, Simms wrote that “it was salutary in the end. It strengthened their souls for the future trial. It made them more resolute in the play. With their own houses in smoking ruins, and their own wives and children homeless and wandering, they could better feel what was due to the sufferings of their common country.” Though at first glance, this might be one bridge too far in attempting to put a positive spin on the wholly negative, Simms raised an interesting question; can we truly fight for that which we love if we have not experienced its loss? Can we understand the suffering of our countrymen if we have not ourselves suffered? Must we? Comfort does, after all, breed complacency; it must be noted that, obviously, comfort encompasses much aside from material luxury. It is a truism that we cannot appreciate what we have until it is lost to us. Scouts brought Marion the devastating news that, just as he and his men had feared, the Tories, under Major James Wemyss, had in their absence “laid waste to the farms and plantations”, in a broad swathe of desolation, “swept by sword and fire.” Indeed, “on most of the plantations, the houses were given to the flames, the inhabitants plundered of all their possessions, and the stock, especially the sheep, wantonly shot or bayoneted. Wemyss seems to have been particularly hostile to looms and sheep, simply because they supplied the inhabitants with clothing…Presbyterian churches he burnt religiously, as so many ‘sedition-shops.’” The General thus led his men homewards again, and they routed a large Loyalist force at the Battle of Black Mingo, driving them from the country. Though the attack still came off according to plan, Marion’s surprise was ruined when his horses crossed a wooden bridge, the sound of their hooves alerting the Enemy; from that point forward, Marion made sure to lay blankets down across bridges to muffle his horses’ hooves. Black Mingo was followed up with another successful ambush at Tarcote, in which some of the treacherous Tories, who had been gambling and reveling in camp, were slain with their cards still clutched in their hands in a macabre tableau. Cornwallis declared that he “would give a good deal to have him taken”, writing to Clinton that “Marion had so wrought on the minds of the people…that there was scarcely an inhabitant between the Santee and the Pee Dee, that was not in arms against us. Some parties…carried terror to the gates of Charleston.” Why was Marion so successful? The guerrilla warfare which he pioneered and mastered was “that which was most likely to try the patience, and baffle the progress, of the British commander. He could overrun the country, but he made no conquests. His great armies passed over the land unquestioned, but had no sooner withdrawn, than his posts were assailed, his detachments cut off, his supplies arrested, and the Tories once more overawed by their fierce and fearless neighbors.” Marion’s notoriety was an inspiration to the scorched and defiled yeomen of South Carolina, responsible for the birth of countless other small partisan bands, their unrecorded exploits now lost to us. Simms continued that “the examples of Marion and Sumter had aroused the partisan spirit…and every distinct section of the country soon produced its particular leader, under whom the Whigs embodied themselves, striking wherever an opportunity offered of cutting off the British and Tories in detail, and retiring to places of safety, or dispersing in groups, on the approach of a superior force.” Tarleton, unable and unwilling to carry on his fruitless and now swamp-arrested pursuit of our hero, was recalled to hound Thomas Sumter. During this withdrawal, Tarleton spoke his most famous words: “Come, my boys! Let us go back. We will soon find the Game Cock [Sumter], but as for this damned Swamp Fox, the Devil himself could not catch him.” The Southern Theater of the War of Independence had a far more savage character to it than the war in the North, notwithstanding the Hessians’ penchant for mounting decapitated Patriot heads on pikes, as “motives of private anger and personal revenge embittered and increased the usual ferocities of civil war; and hundreds of dreadful and desperate tragedies gave that peculiar aspect to the struggle.” Greene wrote that “the inhabitants pursued each other rather like wild beasts than like men”; indeed, “in the Cheraw district, on the Pee Dee, above the line where Marion commanded, the Whig and Tory warfare, of which we know but little beyond this fact, was one of utter extermination. The revolutionary struggle in Carolina was of a sort utterly unknown in any other part of the Union.” Few men escaped the struggle for liberty unscathed. At Georgetown, a party of Loyalists shot Gabriel Marion’s horse out from under him, and, as soon as the young Marion, the General’s nephew, fell he was executed, with “no respite allowed, no pause, no prayer.” Simms wrote that “the loss was severely felt by his uncle, who, with no family or children of his own, had lavished the greater part of his affections upon this youth…who had already frequently distinguished himself by his gallantry and conduct.” Marion grieved to himself, yet was consoled by saying that he “should not mourn for him. The youth was virtuous, and had fallen in the cause of his country!” After this latest depredation, Marion retired to his legendary swamp fortress on Snow’s Island, along the Pee Dee in present-day Florence County. “Retired” is perhaps not the proper word, though, as Marion kept up the fight, continuing operations from his new, perfect, and secure headquarters. As Simms wrote, “The love of liberty, the defense of country, the protection of the feeble, the maintenance of humanity and all its dearest interests, against its tyrant — these were the noble incentives which strengthened him in his stronghold, made it terrible in the eyes of his enemy, and sacred in those of his countrymen. Here he lay, grimly watching for the proper time and opportunity when to sally forth and strike.” Simms described the natural fortress beautifully, writing that “in this snug and impenetrable fortress, he reminds us very much of the ancient feudal baron of France and Germany, who, perched on castled eminence, looked down [as] an eagle from his eyrie, and marked all below him for his own.” Though “there were no towers frowning in stone and iron”, there were better towers, “tall pillars of pine and cypress, from the waving tops of which the warders looked out, and gave warning of the foe or the victim.” Marion did very little to “increase the comforts or the securities of his fortress. It was one, complete to his hands, from those of nature…isolated by deep ravines and rivers, a dense forest of mighty trees, and interminable undergrowth. The vine and briar guarded his passes. The laurel and the shrub, the vine and sweet-scented jessamine, roofed his dwelling, and clambered up between his closed eyelids and the stars…The swamp was his moat…Here…the partisan slept secure.” He camped in “one of those grand natural amphitheaters so common in our swamp forests, in which the massive pine, the gigantic cypress, and the stately and ever-green laurel, streaming with moss, and linking their opposite arms, inflexibly locked in the embrace of centuries, group together, with elaborate limbs and leaves, the chief and most graceful features of Gothic architecture. To these recesses, through the massed foliage of the forest, the sunlight came as sparingly, and with rays mellow and subdued, as through the painted window of the old cathedral, falling upon aisle and chancel.” Tarleton had not named Marion the Swamp Fox for nothing; he was its master. In the swamp, on the Enemy’s own ground, “in the very midst” of the Crown and its minions, he made himself a home. Aside from pure audacity, Marion lived among the Enemy for another reason, for his maxim was that it was always better to live upon the resources of foes than of friends. In his swamps, “in the employment of such material as he had to use, Marion stands out alone in our written history, as the great master of that sort of strategy, which renders the untaught militiaman in his native thickets, a match for the best-drilled veteran of Europe. Marion seemed to possess an intuitive knowledge…He beheld, at a glance, the evils or advantages of a position.” Marion “knew his game, and how it should be played, before a step was taken or a weapon drawn. When he himself, or any of his parties, left the island, upon an expedition, they advanced along no beaten paths. They made them as they went. He had the Indian faculty in perfection, of gathering his course from the sun, from the stars, from the bark and the tops of trees, and such other natural guides, as the woodman acquires only through long and watchful experience.” Total secrecy was one of the keys to his success; before jaunting off on another expedition, the only way for the men to ascertain the distance of their mission was to observe Marion’s cook to see the quantity of foodstuffs he packed. The General “entrusted his schemes to nobody, not even his most confidential officers. He…heard them patiently, weighed their suggestions, and silently approached his conclusions. They knew his determinations only from his actions. He left no track behind him…He was often vainly hunted after by his own detachments. He was more apt at finding them than they him.” When Lieutenant Colonel Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee sought Marion before a joint raid on Georgetown, he could not locate the partisan; eventually, one of Lee’s scouts made contact with a small provisioning party of Marion’s, and even then, his own men spent several hours locating their commander. Though Major General Greene and his Continentals were necessary to restore South Carolina and Georgia to the American confederacy, they were not sufficient; they could not have been victorious without the “native spirit” of the partisans of the backwoods. When Greene arrived at Hicks’ Creek, he found a country “laid waste. Such a warfare as had been pursued among the inhabitants, beggars description. The whole body of the population seems to have been in arms, at one time or another…A civil war, as history teaches, is like no other. Like a religious war, the elements of a fanatical passion seem to work the mind up to a degree of ferocity, which is [far beyond] the usual provocations of hate in ordinary warfare.” He wrote that “the inhabitants pursue each other with savage fury…The Whigs and the Tories are butchering one another hourly. The war here is upon a very different scale from what it is to the northward. It is a plain business there. The geography of the country reduces its operations to two or three points. But here, it is everywhere; and the country is so full of deep rivers and impassable creeks and swamps, that you are always liable to misfortunes of a capital nature.” While Marion never hesitated to fulfill his duty, he was always averse to “those brutal punishments which, in the creature, degrade the glorious image of the Creator.” General Moultrie wrote that Marion “always gave orders to his men that there should be no waste of the inhabitants’ property, and no plundering.” In the punishment of those of his own men who disgraced both him and the Patriot cause, he favored a scornful mercy, merciful insofar as he preferred not to execute men whom he did not have to, yet scornful in that he essentially shunned them with the utmost contempt, a punishment which usually sent them well on their way. Lee, the father of our General Robert E. Lee, adroitly described Marion; unerringly and “enthusiastically wedded to the cause of liberty, he deeply deplored the doleful condition of his beloved country. The common weal was his sole object; nothing selfish, nothing mercenary soiled his ermine character.” Lee continued, “Fertile in stratagem, he struck unperceived, and retiring to those hidden retreats…in the morasses of Pee Dee and Black River, he placed his corps, not only out of the reach of his foe, but often out of the discovery of his friends.” Throughout the arduous course of war through which Marion passed, “calumny itself never charged him with molesting the rights of person, property, or humanity. Never avoiding danger, he never rashly sought it…he risked the lives of his troops only when it was necessary.” He was “never elated with prosperity, nor depressed by adversity.” At dinner one evening, Marion was made aware that a group of Lee’s men were hanging Tory captives; instantly, he “hurried from the table, seized his sword, and running with all haste, reached the place of execution in time to rescue one poor wretch from the gallows. Two were already beyond rescue or recovery. With drawn sword and a degree of indignation in his countenance that spoke more than words, Marion threatened to kill the first man that made any further attempt in such diabolical proceedings.” Even after the War, Marion was merciful to the defeated Tories, declaring, “Then, it was war. It is peace now. God has given us the victory; let us show our gratitude to Heaven, which we shall not do by cruelty to man.” When word reached the Swamp Fox of a British officer abusing some of his men in captivity, he wrote the Redcoat that “I have treated your officers and men who have fallen into my hands, in a different manner. Should these evils not be prevented in future, it will not be in my power to prevent retaliation.” To another British commander, he wrote that “the hanging of prisoners and the violation of my flag, will be retaliated [for] if a stop is not put to such proceedings, which are disgraceful to all civilized nations. All of your officers and men, who have fallen into my hands, have been treated with humanity and tenderness, and I wish sincerely that I may not be obliged to act contrary to my inclination.” Though Marion never wished to sully himself with such excesses, he certainly would if his hand was forced. Marion and his ensemble of yeoman Patriots endured grinding poverty and privation for years, all for the sake of their, and our, liberty. Indeed, Marion himself went over a full year without the meager luxury of a blanket when he slept. His men often trekked seventy miles per day, with nothing to eat but a handful of cold potatoes and a single draught of cold water, clothed only in hair-thin homespun. On one occasion, one of his officers sought to reassure the Swamp Fox that their ammunition situation was not as dire as he feared, telling Marion that “my powder-horn is full.” Marion smiled gently, and replied, “Ah…you are an extraordinary soldier; but for the others, there are not two rounds to a man.” We cannot overstate the destitution of the Patriots, and particularly those Patriots of our Southland. Congress was bankrupt, South Carolina likewise without means. For three years, Simms noted, “South Carolina had not only supported the war within, but beyond her own borders. Georgia was utterly destitute, and was indebted to South Carolina for eighteen months for her subsistence; and North Carolina, in the portions contiguous to South Carolina, was equally poor and disaffected.” How then, was the War to be carried on? Marion’s men “received no pay, no food, no clothing. They had borne the dangers and the toils of war, not only without pay, but without the hope of it. They had done more — they had yielded up their private fortunes to the cause. They had seen their plantations stripped by the enemy, of negroes, horses, cattle, provisions, plate…and this, too, with the knowledge, not only that numerous Loyalists had been secured in their own possessions, but had been rewarded out of theirs.” Simms explained their condition well, writing that “the Whigs were utterly impoverished by their own wants and the ravages of the enemy. They had nothing more to give. Patriotism could now bestow little but its blood.” And yet, as Marion well understood, that blood of patriotism was capable of so much more than just itself. He vowed that, were he “compelled to retire to the mountains”, he would, alone if necessary, “carry on the war, until the enemy is forced out of the country.” To a man, his partisans swore to remain at his side until the bitter end, pledging themselves to “follow his fortunes, however disastrous, while one of them survived, and until their country was freed from the enemy.” To this display of devotion, our hero merely replied, “I am satisfied; one of these parties shall soon feel us.” This iron constitution, this ethereal determination, is no mystery; as Greene wrote to Marion, “Your State is invaded — your all is at stake. What has been done will signify nothing, unless we persevere to the end.” If they did not hold fast and keep up the fight, if they did not seize victory, all that had come before, all of the pain, suffering, and trauma, was for naught. If we do not take back our country, the last two and a half centuries are forever smothered. Greene praised the South Carolinian, continuing, quite rightly, that “to fight the enemy bravely with the prospect of victory, is nothing; but to fight with intrepidity under the constant impression of defeat, and inspire irregular troops to do it, is a talent peculiar to yourself.” Even simpler than that, however, is the simple truth that we are impelled to do whatever it takes to protect and preserve hearth and home; we cannot help but recall that classic of American action, Red Dawn, and its most valuable line: “Because we live here.” Our first War of Independence was no grand triumphal narrative, but an incredibly bitter war of attrition. At its close, the British were finally worn down, their will to carry on pulverized and crumbled to dust. Marion’s men “were not yet disbanded. He himself did not yet retire from the field which he had so often traversed in triumph. But the occasion for bloodshed was over. The great struggle for ascendancy between the British Crown and her colonies was understood to be at an end. She was prepared to acknowledge the independence for which they had fought, when she discovered that it was no longer in her power to deprive them of it. She will not require any eulogium of her magnanimity for her reluctant concession.” Now, the British Army withdrawn from Carolina, “the country, exhausted of resources, and filled with malcontents and mourners, was left to recover slowly from the hurts and losses of foreign and intestine strife. Wounds were to be healed which required the assuasive hand of time, which were destined to rankle even in the bosoms of another generation, and the painful memory of which is keenly treasured even now.” South Carolina, along with all of her sisters, including those already sharpening their knives for her demise, was free. America emerged from its baptismal blood, breaking the chains of Empire, an unprecedented victory achieved in no small part due to the labors of our Swamp Fox, Francis Marion. The partisan par excellence, Marion was the grand master of strategy, the wily fox of the swamps impassable but to him, “never to be caught, never to be followed — yet always at hand, with unconjectured promptness, at the moment when is least feared and is least to be expected.” Historian Sean Busick writes that Marion “kept alive the hope of patriots in the Southern States when victory and independence were most in doubt — after the fall of Charleston and the rout of the Continental Army at Camden. In the darkest hours of the Revolution, when the Continental Army had been run out of South Carolina, Marion and his small band of citizen soldiers took the field against the British Regulars. By keeping up a constant harassment, they made sure the British were never able to rest after their victories in South Carolina, and helped to drive them from the State and toward their final defeat at Yorktown.” When the cause of liberty was uniformly considered hopeless, when all was believed lost, when the blackest shadow fell and threatened to engulf our flickering flame, the consecrated fire was yet kept alive. Simms elaborated that it is to him, more than any other, whom “we owe that the fires of patriotism were never extinguished, even in the most disastrous hours, in the lowcountry of South Carolina. He made our swamps and forests sacred, as well because of the refuge which they gave to the fugitive Patriot, as for the frequent sacrifices which they enabled him to make, on the altars of liberty and a becoming vengeance.” Marion’s name “was the great rallying cry of the yeoman in battle — the word that promised hope — that cheered the desponding patriot — that startled, and made to pause in his career of recklessness and blood, the cruel and sanguinary tory.” At the moment of defeat, in the putrescent slough of despond, the dark before dawn, the people of South Carolina merely waited for the reanimation that only Marion could provide. Simms noted that “the very fact that the force of Marion was so [numerically] insignificant, was something in favor of that courage and patriotism.” Busick affirms that, as we have seen, time and again, the success of the South Carolina Patriots was “due more to the sacrifices of the humble than to the decisions of the famous.” Marion, our Carolinian Cincinnatus, happily returned to the agrarian life which he cherished, but it would not be with ease, as the world was “to be begun anew.” The Revolution left him “destitute of means, almost in poverty, and more than fifty years old.” His small fortune “had suffered irretrievably. His interests had shared the fate of most other Southern Patriots, in the long and cruel struggle through which the country had gone. His plantation in St. John’s, Berkeley…was ravaged, and subjected to constant waste and depredation.” Furthermore, again sharing the fate of all of his compatriots but the upper echelons of the Patriot command, the Swamp Fox “received no compensation for his losses, no reward for his sacrifices and services.” The Congress voted to award the hero, who had sacrificed so much for the new nation, a gold medal; whether or not the medal was actually given to him, though, is up for debate. Before we begin celebrating this honor, Simms cautioned us to understand that “cheaply, at best, was our debt to Marion satisfied, with a gold medal, or the vote of one, while Greene received ten thousand guineas and a plantation. We quarrel not with the appropriation to Greene, but did Marion deserve less from Carolina? Every page of her history answers, ‘No!’” The duty of the warrior is often a thankless one. He was returned to the State Senate by the people of St. John’s, and was later awarded a modest sinecure; his ultimate reward, however, was his legacy. The early Republic revered the Swamp Fox. In our present age of deracinated ignorance, it must come as a surprise that there are more places named for Francis Marion than for any other soldier of the War, aside from President George Washington; as Simms declared, “His memory is in the very hearts of our people.” Upon his retirement from public life and the resignation of his commission in the State Militia in 1794, an assembly of the citizens of Georgetown addressed him thus: “Your achievements may not have sufficiently swelled the historic page. They were performed by those who could better wield the sword than the pen — by men whose constant dangers precluded them from the leisure, and whose necessities deprived them of the common implements of writing. But this is of little moment. They remain recorded in such indelible characters upon our minds, that neither change of circumstances, nor length of time, can efface them. Taught by us, our children shall hereafter point out the places, and say, ‘Here, General Marion…made a glorious stand in defense of the liberties of his country…’ Continue, General, in peace, to till those acres which you once wrested from the hands of a rapacious enemy.” It would without a doubt strike these men as poisoned barbs into their very souls, were they to see the noxious depths to which the education of our children has fallen, were they to discover that, in relatively few generations, the memories which they believed to be so indelibly recorded have faded away. Many of the irreplaceable primary documents regarding the life of Marion were incinerated when Simms’ home, including his Alexandrian library of ten thousand books and manuscripts, was put to the torch when General William Sherman’s rabid horde of fiends sacked and razed his Woodlands plantation. As the gentlemen of Georgetown said, the Patriots of the Carolina backcountry were not learned men, and were in any case too busy bleeding to bother with documenting their exploits. Their tales of unparalleled heroism need not have been written to be remembered; this barely scratches the surface of our failure to live up to their standards, to the shining examples their lives set for ours. A devout Christian, “an humble believer in all the vital truths of faith”, Marion was ready to meet his Maker; he declared, “Death may be to others a leap in the dark, but I rather consider it a resting-place where old age may throw off its burdens.” As he was peacefully translated from our world to the next, he spoke his last words: “For, thank God. I can lay my hand on my heart and say that, since I came to man’s estate, I have never intentionally done wrong to any.” He could die in that sublime satisfaction that he had done his duty, that he had risen to the occasion, just as we now must rise to the occasion and defend to our last that which his generation secured for ours, all of these long years later. We should savor and echo the words of Major General George Pickett, written to his wife one day after his Charge, doomed to fail but destined for enshrinement in the most hallowed annals of Western man: “My brave boys were full of hope and confident of victory as I led them forth…and though officers and men alike knew what was before them, knew the odds against them, they eagerly offered up their lives on the altar of duty, having absolute faith in their ultimate success. Over on Cemetery Ridge, the Federals beheld a scene never before witnessed on this continent, a scene which has never previously been enacted and can never take place again — an army forming in line of battle in full view, under their very eyes — charging across a space nearly a mile in length…moving with the steadiness of a dress parade, the pride and glory soon to be crushed by an overwhelming heartbreak. Well, it is all over now. The battle is lost, and many of us are prisoners, many are dead, many wounded, bleeding, and dying. Your Soldier lives and mourns and but for you, my darling, he would rather, a million times rather, be back there with his dead, to sleep for all time in an unknown grave.” Pickett signed as “your sorrowing Soldier.” As we approach ever-nearer to the precipice, to what appears and threatens to be a danger graver than any that we have ever faced, it is easy to fold, to crumple under the tremendous weight of it all. As John Derbyshire writes, we live in “an occupied nation, dominated by a bizarre cult of anti-white totalitarianism, against which we dissenters have no organization, no leadership, and almost no public voice. It is hard to think that this will end well.” We are, by design, made to feel completely alone. But we are not. While our dismal condition is on the path to eclipse that which faced our Confederate ancestors, and while we stand on the cusp of a terrible darkness, a palpable evil permeating the air in our dying land, all is not lost. We must carry the fire, just as that great South Carolinian Francis Marion did, holding his hands cupped around the embers of faith, keeping hope kindled in the bosoms of his people, our people. Make no mistake — while, now, the Enemy tears down and casts asunder our monuments, our physical memories serving as proxies for the cultural memories that we have failed so spectacularly to inculcate in our brainwashed children, memory is not their ultimate target. No, their target is us. When we see our monuments defiled and obliterated, know that it is mere sublimation. This is what they desire for us, our monumental marble nothing less than transubstantiated blood. And yet, they cannot succeed while one of us lives; Donald Livingston, President of the Abbeville Institute, recently likened our position to that of monks, preserving our sacred texts against the darkling gloom, for a brighter day ahead. This is of course, however, the worst-case scenario, only the case if we have not taken our stand in time to prevent ruin. In these deflating days, the fires apparently too numerous to extinguish, my spirits were immeasurably lifted upon being blessed to attend the 147th Confederate Memorial Day at the Confederate Cemetery in Fayetteville, Arkansas. This idyllic patch of land, lost in time, is maintained solely by the devotion of the Southern Memorial Association, a group of valiant Southern women, our great treasure as always. How heartening it was to see these women, and their many supporters, spend their time and money to honor our ancestors, to preserve their beautiful resting-place; for a century and a half, these proud Southrons have gathered to remember their forefathers of the Trans-Mississippi and the selfless deeds which they wrought, echoing in our hearts even now. These are the men whom we must emulate; their golden example, itself following that of our Swamp Fox, must be our beacon in the roiling gale now overtaking us. Each unmarked grave, most holding the bones of men lost at the disastrous Battle of Pea Ridge, was adorned with a brilliant battle-flag, the sight of which never fails to fuel the fire within. A lovelier sight we have yet to behold. Several dozen people turned out; though the mood was certainly somber, we drew strength from one another, and cut a scene that could not have been any different from the anarchy reigning in cities across the “United” States of America. After some speechifying from representatives of the Association, the Sons, and the Daughters, we dedicated new markers for each section of the cemetery, Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, and Louisiana, and laid wreaths at the foot of the gorgeous, pristine monument at its center. The marker for the Arkansawyer veterans reads, “Weep, for richer blood was never shed.” On the monument is inscribed, “These were men whom power could not corrupt, whom Death could not terrify, whom defeat could not dishonor.” The band played Dixie.

0 Comments

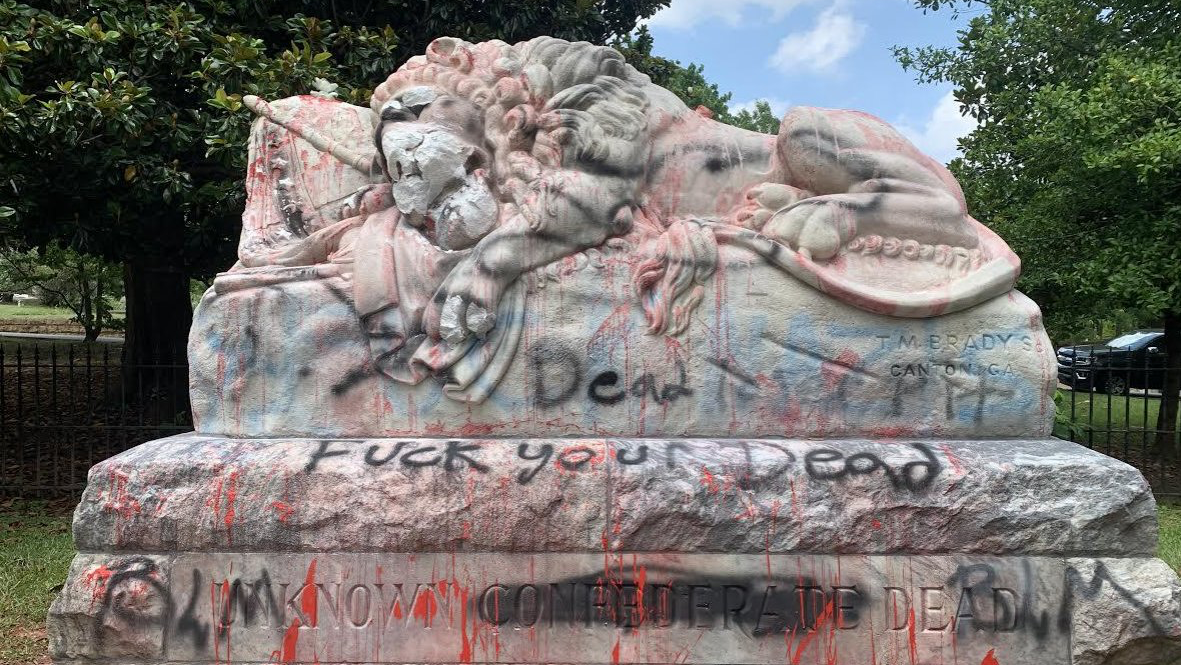

We have just witnessed Kristallnacht for traditional America. We are no longer welcome in the land that we love, the nation that our, and only our, forefathers built from nothing — the only home, not only that we have ever known, but that we will ever know. This is one more turn in the revolutionary spiral, and perhaps the opening shot of hot civil war, if our Cause can even muster up a quorum. A friend of mine, about half a century my senior, remarked that this is not the country that he grew up in; indeed, I replied, this is not the country that I grew up in, not all that long ago. Our riven homeland burns, convulsing in the throes of revolutionary political and racial violence. The arsonists that set fire to our cities, to countless unknown and weeping American Dreams, are but the brownshirts of the Egalitarian Regime; far from “resisting” the System, they are its craven handmaidens, supported in defilade by all of the money in the world. They are chess pieces, acting out the inorganic revolution from above which has been so perfectly planned and plotted for at least the last eighty years; for those eight long decades, as the Right was censored, crushed, fragmented, and scattered to the winds, the Left, largely through the assistance of its Republican houseboys, has grown ever-more exorbitantly financed and hardened, as it captured all of our institutions, one by one. As Paul Gottfried warned almost twenty years ago, the Protestant Deformation of the twentieth century has resulted in a system of Puritan fervor wholly disconnected from God, a truly secular theocracy which features its own “original sin”, soteriology of perpetual ethnomasochistic atonement, clerical hierarchy, excommunicative social mechanism, millenarian-utopian eschatology, and even a system of human sacrifice, as the unborn are offered up to the Moloch of “Progress” every single day. The throngs of savage and insatiable rioters, backed up by legions of groomed and manicured apologists, are the only logical consequence of indoctrinating an entire generation or two into the perverse conviction that white men are the root of all evil, that blacks and transgenders built America, that the United States were founded for the express purpose of oppressing “minorities.” From the oak-paneled corridors of that bottom of the barrel so speciously called “the Ivy League”, all the way down to the bloody streets has trickled variations of that dreadful call, “Kill the Boer.” Our Cause faces unprecedented repression, repression which will only escalate into something far worse. What of the business owners across the realm who, already crippled by the patently unnecessary and wrongheaded lockdowns that have been so transparently abandoned by the ruling class amidst the chaos fomented by their egalitarian brownshirts, awoke to the sight of their life’s work in ashes, to their community reduced to a smoking ruin that can no more stand being, as Gregory Hood put it, “papered over with money, drugs, alcohol, and television to fill the empty hole that used to be a country”? How much more anarcho-tyrannical humiliation can we bear? Will we simply go quietly into our corners, drink ourselves into a stupor, inject ourselves with heroin, and die gently in the black night, or will we rage against the dying of the light? We put all of our heroic ancestors to shame. Not one soul, nary a one of their descendants was there to defend any of their monuments as they were defiled and toppled. Our absurdly heavily militarized police stood by as America was put to the torch. Our “law and order” President, the latter-day James Buchanan, cowered in his bunker, just as he has for four years as his supporters have been incessantly harassed, beaten, and brutalized in the streets. He will lose this election, and he deserves to. The Republican Party, which must be destroyed and rebuilt, exists to harness the Southern spirit and redirect it straight into the ground. Our Cause has suffered as never before under the Trump Administration. Two of my friends accurately embody an all-too-common sentiment that I see expressed in the former Confederacy today; one simply said that sitting on the lake with his family was more rewarding than anything else, better than “trying to control the uncontrollable.” His eyes are fixed totally on eternity with our Lord and Savior, rather than the here and now; he would rather enjoy the simple things than participate in the filthy game of politics. Similarly, another friend, somewhat wryly, told me that all that he desires is his forty acres and a mule, his shady lane, his little piece of Heaven on earth, surrounded by a moat and protected by the Castle Doctrine. He “cannot take the rhetoric anymore, regardless if it is yours, mine, or Satan’s.” I responded by stating that “everything is politics”, to which he compared me with the Leftist thugs remaking our world in the image of the Marquis de Sade. I clarified, explaining that I do not mean that everything must be political, but rather that everything is political, for everything that we hold dear is under the gun, staring a rifle barrel in the face. For example, take our families, or a simple chipmunk on the Buffalo. When we are with them, when we are out in the natural world, nothing else matters. None of our earthly concerns seem significant. And yet, at these very moments in which we are most at peace, evil forces gather with the sole purpose of taking from us all that we love. We are compelled by duty, compelled by God, to hold fast to these things by fighting for them, these things that would otherwise seem to be apolitical. Thus, we are forced to conceptualize everything in political terms. Stated differently, we may not want war — but war wants us. Christ made clear to us that “he that is not with me is against me; and he that gathereth not with me scattereth abroad.” (Matthew 12:30) The time for fence-sitting, if there ever was one at all, is long past; Christ knows “thy works, that thou art neither cold nor hot: I would thou wert cold or hot. So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth.” (Revelation 3:15-16) Until Christ returns, there is no one coming to save us. It is we alone who must reclaim our birthright. We must remember that a minority, albeit a sizable minority, of the American colonists joined the Patriot cause; the tomes of history tell us that nations are often fundamentally transformed and dragged into revolution by tiny minorities, a fact which should both terrify and invigorate our Cause. We need not gain a majority of those of our fellow citizens who have strayed from the path and fallen under the ephemerally glimmering song of the siren. Gideon should serve as our example, annihilating with God the wretched Midianites, overcoming a vast army with only three hundred men whose rallying cry was, “The sword of the Lord!” (Judges 6-8) In order to understand our condition, we must understand the Enemy, the totalized, totalizing, alienated, and alienating Egalitarian Regime. A wonderfully sober approbation of the situation is elucidated in the brilliant film Ride with the Devil, accurately portraying the brutal partisan war of extermination waged between the Bushwhackers and Jayhawkers in Missouri during the War for Southern Independence. A friendly Confederate sympathizer who has opened his home to a band of patriots has the following exchange with one of the partisans: And why, if you do not mind my askin', did you not join the regular army? Army? Well, we thought of it. I suppose we decided this fight has got to be made in our own country, not where some general tells us it should happen. It soon will be everywhere. My family and I, we will be quittin' this house in the spring. As soon as the roads are clear, we're gonna be tryin' for Texas. About half of Missouri's went to Texas. Now, the whole state's thick with invaders. We cannot drive them away. We have different thoughts. I still want to fight. I reckon I'll always want to fight them. Always. Have you ever been to Lawrence, Kansas, young man? No, I reckon not, Mr. Evans. I don't believe I'd be too welcome in Lawrence. I didn't think so. Before this war began, my business took me there often. As I saw those Northerners build that town, I witnessed the seeds of our destruction being sown. The foundin' of that town was truly the beginnin' of the Yankee invasion. I'm not speakin' of numbers, nor even abolitionist trouble-makin'. It was the schoolhouse. Before they built their church, even, they built that schoolhouse. And they let in every tailor's son and every farmer's daughter in that country. Spellin' won't help you hold a plow any firmer. Or a gun either. No, it won't, Mr. Chiles. But my point is merely that they rounded every pup up into that schoolhouse because they fancied that everyone should think and talk the same free-thinkin' way they do with no regard to station, custom, propriety. And that is why they will win. Because they believe everyone should live and think just like them. And we shall lose because we don't care one way or another...how they live. We just worry about ourselves. Are you sayin', sir, that we fight for nothin'? Far from it, Mr. Chiles. You fight for everything that we ever had. As did my son. It's just that we don't have it anymore. Mr. Evans, when you get back from Texas, it'll all be here waitin' for you. Jack Bull and me, we'll see to it. Well...yes. Thank you, son. Well, enough of this war talk. Our Enemy is unified around one goal — to remake the world in its own image. While we worry about our families and ourselves, they are consumed with the basest hatred; they envy us, for our existence is an affront, a reproach to their misery. They are driven to destroy what they could never create. All of the centuries of blood and toil that we have spilt and spent to carve out our splendid niche can be undone in a matter of minutes, for as we must now realize, Heaven is far away, but Hell can be reached in a day. It often seems as if they have won, as if the war was lost before it was given a chance to begin, as if we have squandered each and every opportunity until finally it is too late. I must confess to feeling discouraged and disheartened on occasion, and to the shedding of tears in morose lamentations of doom and gloom. A friend recently sent me a video, a clip from some BBC nature documentary, which nourished that foundering fire in my heart. In the video, a noble, gallant, and solitary lion attempts to fight off a horde of vile hyenas; alone, despite his virtue, despite the fact that he is so much better than they can ever hope to be, he does not stand a chance. Our hearts in our mouths, we watch aghast as the despicable beasts wear him down. Yet in his hour of greatest need, in his direst straits, a fellow lion sees him in his travails and gallops to his aid. Now, the odds have changed; even for twenty hyenas, a pair of lions is too much to take on. As the hyenas tuck tail and dissipate, the lions bond, brothers in arms. We must unite in this, our darkest hour yet, for together we stand, and in isolation we fall, quickly and quietly. We must also remember that it is always darkest before dawn, and in this spirit, must look to the shining light of Brigadier General Francis Marion, the Swamp Fox, who alone fed the degraded and persecuted Patriots of South Carolina the steady diet of hope that was their sustenance when all truly appeared to be lost in our first War of Independence. There is much in Marion’s life and in his glorious guerrilla campaign from which we may glean vital tactical lessons, and, more importantly, to give us the inspiration that we so desperately need. Of Huguenot stock, Marion first cut his teeth in the ways of war in 1759, during the Cherokee War in South Carolina, a conflict that occurred in the midst of the French and Indian War, itself a theater of the Seven Years’ War. That tribe of Amerindians was returning from service in a British campaign against the French, when hostilities commenced with the Southern colonists; as William Gilmore Simms, Marion’s finest biographer, described, “The whole frontier of the Southern Provinces, from Pennsylvania to Georgia, was threatened by the savages, and the scalping-knife had already begun its bloody work upon the weak and unsuspecting borderers.” In this strife, Lieutenant Marion served under the immediate command of William Moultrie; in one spectacular engagement, Marion led the vanguard to dislodge the Cherokee from their stronghold atop a hill near the town of Etchoee. By sheer determination, a preview of the attritional warfare which he would later pioneer, he succeeded in driving the merciless savages from the field. In the tumultuous year of 1775, Marion was sent by his community to serve as a delegate to the Provincial Congress of South Carolina, as a member from St. John’s, Berkeley, at which the proud people of South Carolina were committed to the Revolution. Marion was subsequently made a Captain in the Second Regiment, of which Moultrie was made its Colonel. As aforementioned, though, the Patriot cause was by no means ascendant; in fact, their condition, especially in the Southern colonies, was much the opposite. The Loyalists, Simms explained, “carried with them the prestige of authority, of the venerable power which time and custom seemed to hallow; they appealed to the loyalty of the subject; they dwelt upon the dangers which came with innovation; they denounced the ambition of the patriot leaders; they reminded the people of the power of Great Britain — a power to save or to destroy…They reminded the people that the Indians were not exterminated, that they still hung in numerous hordes about the frontiers, and that it needed but a single word from the Crown, to bring them, once more, with tomahawk and scalping-knife, upon their defenseless homes. Already, indeed, had the emissaries of Great Britain taken measures to this end…What was the tax on tea, of which they drank little, and the duty on stamps, when they had but little need for legal papers?” Ambition and Mammon-lust have driven our pharisaical ruling class, the institutional barons of the Egalitarian Regime, to treason. The deplorable traditions which we so bitterly cling to are nothing but obstacles in their reductive vision of conquest; they have gleefully abandoned duty, faith, and permanence in so many short sales, exchanged for ephemeral power and prestige. Satan reigns in earthly corruption, and his mortal world hates us. Unlike the engorged, opulent, respectable cocktail conservatism of David French and “Pierre Delecto”, our Cause constantly teeters on the verge of poverty; as such, we must follow the lead of Marion’s ragtag band of brothers, for whom “faith and zeal did more…and for the cause, than gold and silver.” We, as dissidents, must understand that the path ahead is not an easy one, that the falling night is dark and full of terrors. Loyalists also tried to instill fear into the colonists by implanting the seed of doubt, that perhaps the Empire was just too powerful, too big to fail; we cannot allow our insecurities to be manipulated. As we saw with the Chinese coronavirus, our rulers are willing to exploit any situation to solidify power and strip us of our most fundamental liberties; witness the Faustian bargain that was made in the aftermath of 9/11, whereby our privacy was forever surrendered, never to return. What else are we to make of the Regime’s simultaneous efforts to both generate bloody chaos on the streets, releasing criminals from prison and weakening law enforcement, and to deprive us of our means of self-defense from that artificial bedlam? The Enemy imposes the emotional, physical, and even sexual isolation of social ostracism as a highly effective weapon as well, one that many men, and even more women, cannot withstand. We must reckon with the fact that not all men can bear this burden; fortitude is a rare gift. Even in the midst of pitched battle, Simms noted, “no man is equally firm on all occasions. There are moods of weakness and irresolution in every mind, which is not exactly a machine, which impair its energies and make its course erratic and uncertain.” An important thing to remember here, though, is that Christ warned us that we would be hated, that we would be persecuted for his name; if we were receiving the plaudits of the damned, the honors of the dishonorable, we would be doing something horribly wrong. One of Marion’s greatest skills was his ability to foster a strong camaraderie among his men, thereby neutralizing the Achilles heel of the militiaman, the fact that, unlike regular troops, “they never forget their individuality. The very feeling of personal independence is apt to impair their confidence in one another. Their habit is to obey the individual impulse…So far from deriving strength from feeling another’s elbow, they much prefer elbow room. Could they be assured of one another, they were the greatest troops in the world. They are the greatest troops in the world—capable of the most daring and heroic achievements — whenever the skill of a commander can inspire this feeling of mutual reliance.” Marion transformed his untrained farmer-partisans into a quasi-männerbund, the ideal cultural unit of the Indo-European Germanic warrior. The most seductive argument employed by the Loyalists, aside from that of security, was their appeal to the base self-interest that holds our population under the yoke; why care about the tax on tea or the duty on stamps if they do not affect us? This is the very jaundiced individualism that persuades otherwise patriotic men to capitulate, to go along to get along, to live on their knees. Men who fall prey to this mentality abandon their communities, their ire only aroused when they themselves are affected. These are the neoconservatives who, when challenged on the Patriot Act, respond, “If you don’t have anything to hide, you have nothing to worry about.” The Regime draws much of its power from an undermined and coopted morality, a belief system fluid in all but its annihilation of life and its elevation of death, its erasure of civilization and advancement of barbarism. The sicker, the more perverse, the better. Our rulers are thus compelled to signal their virtue by making ever-increasingly pathetic acts of penitence and propitiation; they are good, moral, and virtuous, while we are “intolerant”, “irrational”, and “bigoted.” It is thus imperative that we restore the Christian morality upon which our nation was built, that we replace the secular theocracy and reconquer the moral landscape. As part of this optical struggle to win the narrative war, we must be careful as to how our aims are expressed; while we must remain true to our words, we must remember our audience. For example, in the earliest phases of the War of Independence, the Patriots were cautious to use only the language of absolute necessity, alongside vague assurances of fealty to the Crown. Quite tellingly, despite the fact that this fooled approximately nobody, as large numbers of Patriots certainly already entertained and enjoyed the idea of national independence, the Patriots still felt that, as Simms wrote, “the people were not prepared for such a revelation — such a condition; and appearances were still to be maintained.” Promoted to Major, Marion was ordered to Fort Sullivan, then little more than an outline. The fort was not even half-finished, made of palmetto logs, with a hastily-constructed palisade and one completed sand-filled wall. Upon the appearance of a British fleet, General Charles Lee urged retreat, calling the unfinished fort a “slaughter pen”; thankfully, South Carolina President John Rutledge did not concur. During the ensuing Battle of Sullivan’s Island, the palmetto logs, laid over sand, withstood the British naval bombardment. One MacDonald was killed, his last words, “Do not give up; you are fighting for liberty and country.” Fort Sullivan was renamed Fort Moultrie, after its defender, and Marion was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel for his service in the victory. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island thus provided the Patriots of the South a wonderful morale boost, piercing and then tarnishing the aura of British invincibility, as well as staving off the invasion of Carolina for another three years. The most lasting legacy of the battle, however, is the noble flag of South Carolina. At the behest of the Revolutionary Council of Safety, Moultrie designed the “Liberty Flag” for South Carolinian troops, consisting of a white crescent in the upper left corner of a blue field, the word “liberty” written in the crescent. First flown at Fort Johnson, on James Island, this is the flag that flew over Fort Sullivan during its defense. Shot down, Sergeant William Jasper braved enemy fire to retrieve and raise it until it could be mounted again; the Moultrie Flag thus became the Revolutionary standard in South Carolina, the first American flag to fly in the South. In 1861, over one century later, the independent State of South Carolina created its secession flag, adding the palmetto tree to the Moultrie Flag, in honor both of Moultrie’s defense of the fort, and of the palmetto logs that had absorbed British fire so well. In the winter of 1778, and then in the spring of 1780, the Southern strongholds of Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina, fell to British rule. It was sheer luck, or perhaps, we believe, something greater than fortune, that Marion’s services were not lost to us in the fall of Charleston. Shortly before its capture, he had marched into the city from Dorchester, and, “dining with a party of friends at a house [on] Tradd Street, the host, with that mistaken hospitality which has too frequently changed a virtue to a vice, turned the key upon his guests, to prevent escape, till each individual should be gorged with wine. Though an amiable man, Marion was a strictly temperate one. He was not disposed to submit to this too-common form of social tyranny; yet mot willing to resent the breach of propriety by converting the assembly into a bull-ring, he adopted a middle course…Opening a window, he coolly threw himself into the street. He was unfortunate in the attempt…the height [was] considerable, and the adventure cost him a broken ankle.” His injury totally disabled him from service, and, pursuant to an order of General Benjamin Lincoln for “the departure of all idle mouths”, Marion quite unhappily departed the city on a litter, while passage still remained open. Though the warrior was presently out of action, his services lost as he convalesced at home in St. John’s parish, his present misfortune spared and secured him for future glory. His best was yet to come.

|

Archives

July 2022

|

Proudly powered by Weebly